The episode illustrates the challenges historically Black colleges and universities face as they seek to leverage their legacies of trust within African American communities to bolster lagging Black enrollment in Covid-19 vaccine clinical trials. Their recruitment efforts will need to overcome the deep-seated suspicions many Black Americans hold toward medical researchers, pharmaceutical companies, and the government that stem from long-standing racial injustices perpetrated by those institutions.

Now, as the four HBCU medical colleges prepare to host Covid-19 vaccine trials on their campuses, there’s hope their efforts will have more success.

“We’ve engendered a level of trust with communities of color that other organizations, quite frankly, just don’t have,” said James Hildreth, an immunologist and president of Meharry College of Medicine in Nashville. “It’s imperative for us as HBCUs to rise to this occasion because people need us.”

Meharry College plans to begin a trial of a vaccine made by Novavax within the next two weeks, with Hildreth as its first participant. The goal is to enroll 300 at the site, but Hildreth thinks they can enroll 600 people, mostly African Americans. The other HBCU medical schools, Howard University College of Medicine in Washington D.C., Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, and Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles, are planning to start their trials in the coming weeks.

“By engaging with the four Black medical schools,” Hildreth said, “they will have individuals who look like them, sitting across the table, having these conversations, and we think that’s going to make a huge difference.”

As the death toll passes 210,000, the Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare inequalities within the U.S. health care system and labor force, with a large portion of Black workers employed in essential jobs that put them at risk of infection. Black Americans are three times as likely as white Americans to contract the disease, five times as likely to end up in the hospital, and twice as likely to die from it, according to the CDC. Had Black Americans died at the same rate as white Americans, some 20,800 Black people would still be alive.

Yet, clinical trials for vaccines are struggling to recruit from their communities. Moderna, one of the drug companies testing a shot, slowed down its trial after failing to enroll enough people of color among its 30,000 participants — though as of last week it said one-third of volunteers were from “diverse communities.” Pfizer and BioNTech reported that 9% of their U.S. clinical trial enrollees are Black and 13% are Latino, while some 72% are white.

“Watching all throughout the summer, you kept seeing stories that say there aren’t enough African Americans in these trials,” said Kimbrough. “You had people like Tony Fauci saying that’s going to be a problem if we create this vaccine and it doesn’t work for Black folks.”

Though people are all nearly identical genetically, people of color might respond differently than white people to a vaccine, especially for a respiratory disease, due to social differences such as exposure to air pollution that disproportionately affects Black and brown communities, or higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes or sickle cell.

“How we live and where we live impacts how medicine affects us,” said Kimbrough. “I think that’s a powerful conversation that we need to be having.”

He enrolled in a Phase 3 trial of the Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine after Verret mentioned in a phone call that he’d done the same, through New Orleans’ Ochsner Health system. The study is double-blinded, so neither the participants nor the researchers know whether they received the vaccination or a placebo until the trial is over. (Because the vaccine doesn’t contain any live virus, the participant has no risk of developing Covid-19 from the injection.)

In their letter, Kimbrough and Verret addressed the pain caused by the Tuskegee syphilis study — in which Black patients were told they would be treated for the disease but weren’t — and how it eroded trust between the Black community and health care providers.

“We understand they’re scared, we understand the history,” Kimbrough said, “but we’re not just telling them this, we’re saying, ‘Look, we’re doing this.’”

Outrage poured in nonetheless, fueled in part by a ProPublica story published a day before the presidents’ letter that found Ochsner had sent Black patients infected with coronavirus home to die despite the threat they could spread the disease to other people.

To Tevon Blair, a 2018 Dillard graduate, part of what made the letter unpalatable was the absence of predominantly white local universities such as Loyola and Tulane.

“The red flag in this vaccine trial … is that it is not a city-wide partnership with other colleges,” Blair tweeted.

Myles Bartholomew, 22, a 2020 Xavier graduate who is pursuing his doctoral degree at Brown University in molecular biology, cellular biology and biochemistry, said that from a researcher’s point of view, he understood the importance of encouraging Black people to take part in clinical trials and said the presidents were acting unselfishly.

“And then from a student’s perspective, there’s a lot of panic and trepidation about anything related to Covid right now,” Bartholomew said. He said he would not enroll in a clinical trial for a Covid-19 vaccine and he understands why other Black people wouldn’t either due to distrust of medical research.

“Those horror stories are something that is part of our history as African Americans, so we’d be completely naive to ignore the precedents that have been set,” he said.

The presidents responded to the social media criticism.

“There was some misinformation that was being exaggerated,” said Verret. “The suggestion that there was money being paid to me or Dr. Kimbrough? No. That there was money paid to Xavier. No. That Xavier was requiring that all students be in the trial. No.” He added that any of the standard clinical trial compensation he received — participants are paid a nominal sum for their time — he would donate to his parish.

The presidents’ letter may have helped make some headway in aiding recruitment, said Julia Garcia-Diaz, the principal investigator of the clinical trial at Ochsner. After it went out, she received an email from a woman in her late 60s who said she read the presidents’ note and wanted to sign up.

“Not only was she elderly and African American, but she was a female also,” said Garcia-Diaz. “She ticked all sorts of boxes because women are also underrepresented in clinical trials.”

Kimbrough said if he were to rewrite the letter, he would have addressed it to the general public rather than just his and Xavier’s campus communities.

“That’s a good lesson in terms of messaging,” he said.

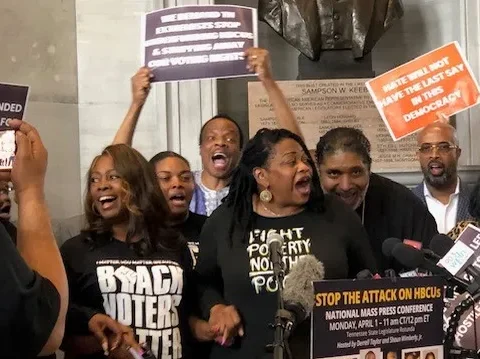

The HBCU medical schools have been working to make sure they get the messaging right as they address people’s skepticism. Their outreach includes interacting with faith-based organizations and participating in virtual town halls, like one hosted in September by Howard University’s radio station and The Black Coalition Against Covid-19.

“The major concern that people are expressing is the question, ‘Am I being experimented upon?’” David Carlisle, the president of Drew and an internist, said during the town hall. “I can assure individuals that this vaccine when you are taking it to fight Covid-19 is not an experiment that is being directed against the African American community.”

He added that anyone considering enrolling should first ask their doctor if they should take this vaccine, why, and is this vaccine safe for them?

At Morehouse, Valerie Montgomery Rice, the president and an OB-GYN, is no stranger to recruiting diverse populations into clinical trials. When she helped run a clinical trial for a birth control pill at the University of Kansas in the 1990s, her site was commended for recruiting the highest percentage of minority women in the country. She said she is confident 60% to 70% of the people enrolled in the vaccine trial on her campus will be people of color, because Morehouse has long cared for the community.

“The benefit that is with an HBCU medical college is that we deal with these issues everyday with our community. We are more culturally sensitive and more culturally aware,” said Montgomery Rice. “We have the trust of the community and we’ve earned that trust.”

Nicholas St. Fleur is a University of Michigan Knight-Wallace reporting fellow.