Kamala D. Harris, a Black woman, is the vice president-elect of the United States. A range of other Black women helped to make this happen: Stacey Abrams, who is responsible in large part for the unprecedented voter turnout in Georgia, and Keisha Lance Bottoms, the mayor of Atlanta. Also deserving credit is Nikema Williams, who won Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, which included Clayton County and was formerly represented by John Lewis until his passing.

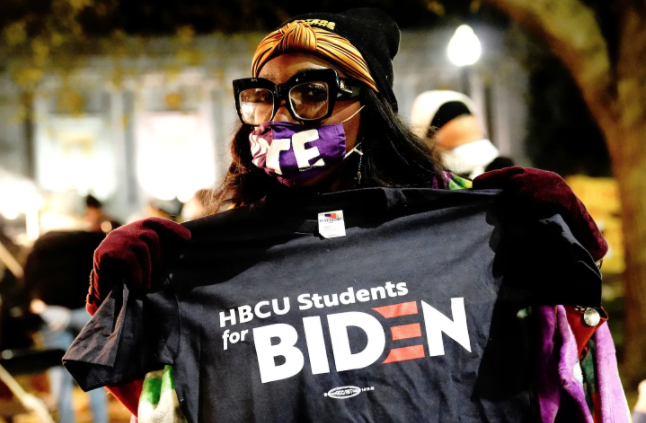

They all have one thing in common: They received their education at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Harris attended Howard, Abrams attended Spelman, Bottoms attended Florida A&M, and Williams attended Talladega. HBCUs are important producers of Black female leaders. Many of these colleges have fostered an institutional climate that makes room for the ideas, voices and leadership of their female students. From their inception in the 19th century, HBCUs have promoted a more inclusive idea of “We the People,” by providing educational opportunity to African Americans, Native Americans and women before it was common to do so. The diversity we see in American politics today is in large part due to these institutions, which nurtured Black leaders, political thinkers and strategists.

The Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended, defines an HBCU as “any historically black college or university that was established before 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association.” Today, there are more than 100 HBCUs in the United States, including public and private institutions, two-year and four-year schools, medical schools and law schools. During the era of legal segregation, these institutions provided educational opportunities to Black students excluded from White colleges, but now students from all races attend these schools.

While the first HBCU, now called Cheyney University, was founded in Pennsylvania in 1837, most Black colleges were founded after the Civil War in the South, when literacy became legal for Black Americans. Before and after emancipation, Black men and women pooled their meager resources and established schools because they understood the links between education, freedom and citizenship. They established more than 100 HBCUs, often with the help of Northern religious groups, to train teachers who would staff the Black elementary schools dotting the South.

Just as education was political, given white supremacists’ strategic refusal to provide it to Black people, Black colleges have been sites of political activity for many generations. These institutions were often counted out and ignored by White leaders and White media, but this neglect allowed them to become instrumental in the long Black freedom struggle. In the 1880s, John Mercer Langston opened present-day Virginia State University with an all-Black faculty holding fast to the idea that Black people had the ability to control their own university.

This ethos persisted. Undaunted by nightriders, white supremacists, paternalistic White benefactors and racist state legislators who underfunded Black education, HBCUs kept building, kept opening their doors and kept offering Black students an education that was bold, visionary and responsive to their needs.

Political activity on and off campus expanded over time as well. In 1934, Howard students picketed the House of Representatives dining hall that refused to serve the lone African American in Congress. In 1960, students at N.C. Agricultural and Technical College sat in at a Greensboro lunch counter, launching the student sit-in movement. In 2004, Black women at Spelman College took on rappers for the denigration of Black women in music videos. In every instance, HBCUs fostered this activism by affirming the humanity of their students.

Many HBCU graduates went on to become political organizers and leaders. Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, the Alabama State College professor who started the Montgomery bus boycott, earned her degree at Fort Valley State College. Thurgood Marshall, one of the architects of school desegregation and the first African American on the United States Supreme Court, was a two-time HBCU graduate, attending Lincoln University of Pennsylvania and Howard University School of Law. While Marshall was at Lincoln, he participated in extracurricular organizations with fellow student Kwame Nkrumah, who would go on to be the first prime minister and president of Ghana after leading the Gold Coast to win independence from Britain. Barbara Jordan, the Texas lawyer and congresswoman whose thorough understanding of the Constitution helped reveal President Richard M. Nixon’s misdeeds, majored in political science at Texas Southern University.

Harris, Abrams, Bottoms and so many other HBCU alumni came of age in these nurturing environments. They walked halls where Ella Baker, Martin Luther King Jr. and Julian Bond had once been students, and that history is more than a legacy. It is a tradition of excellence and a birthright to soar. It is a mandate to stand up and speak up.

HBCU students learned from a long list of administrators and faculty, including luminaries like Benjamin Mays, Ralph Bunche, Charles Hamilton Houston, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Norman Francis and others, who taught that education was about more than obtaining a degree.

For example, under Bennett College President Willa Player’s leadership during the civil rights era, students at the school for women participated in sit-ins and sponsored a door-to-door voter registration drive, registering more than 1,000 African Americans. At one point in spring 1963, one-third of the Bennett student body sat in jail because of their activism. Player voiced full support for her students and devised a system to distribute mail and assignments to the jailed women. In embracing the political work of Black college women, Player suggested that the ongoing civil rights movement was not simply a man’s movement. Women had a role to play alongside and independently of men.

And when HBCU administrators have neglected to support student activism, students have responded by challenging the status quo on their own campuses. From Bennett to Bowie State, Alcorn State to Xavier, students were at the forefront of efforts to add Black Studies to the curriculum and to have student-run judiciary systems for student discipline. From these internal struggles, HBCU student leaders developed a Black consciousness and learned the value of activism.

It should have come as no surprise, then, that when Harris launched her presidential campaign, she did so on the Howard campus that nurtured her confidence and shaped her political acumen. Despite Harris’s impressive career and political achievements, there is a pervasive belief that HBCUs do not prepare students for the real world because the institutions are majority Black in a White world. The 2020 presidential election has debunked that myth and demonstrated that HBCUs have prepared their alumni to change the world one precinct, one county and one state at a time.

Anna Julia Cooper, a graduate of St. Augustine’s, wrote in the 1890s that only the Black woman can say “when and where I enter, in the quiet undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.” As Harris prepares to be our country’s first female vice president, she brings the history, legacy, preparation and salience of HBCUs with her to the role.