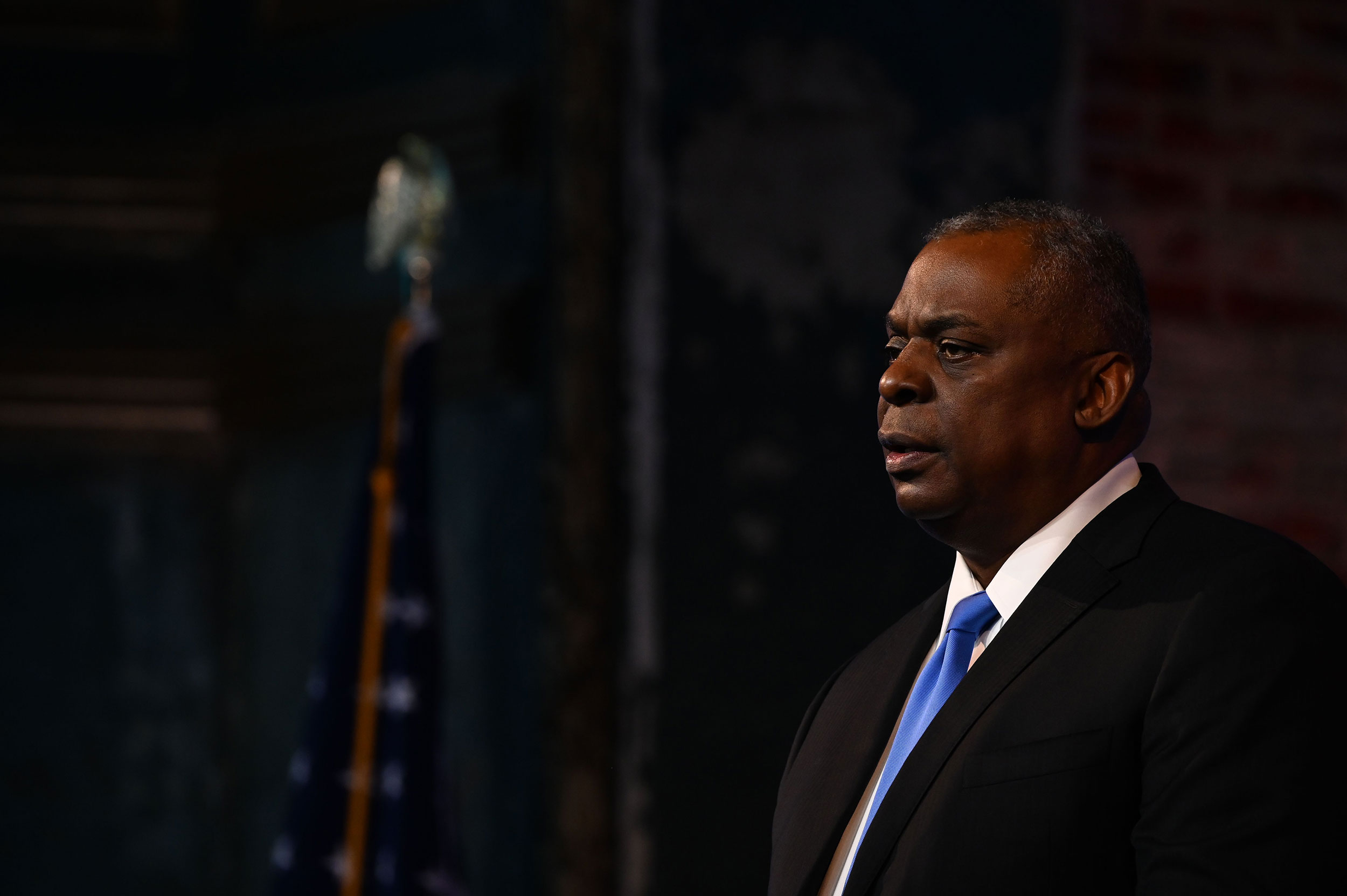

Shortly before Austin announced a staggered pause and review of domestic extremism within the ranks, known in the military as a stand down, he emphasized to those in attendance that the vast majority of service members conduct themselves with honor and integrity but stressed his determination to find out how many espouse beliefs and ideas antithetical to the values of the military.

It is one of a number of early priorities that have made Austin’s first days at the Pentagon very different from his predecessors’, focusing internally on issues within the military, instead of outward on adversaries abroad.

As well as domestic extremism, Austin has directed the Pentagon to tackle sexual assault and review the department’s numerous advisory boards and committees during a period when most of his predecessors were already visiting key US allies around the world shortly after their swearing-in.

“The job of the Department of Defense is to keep America safe from our enemies. But we can’t do that if some of those enemies lie within our own ranks,” Austin said at his confirmation hearing.

In addition, Austin pegged coronavirus as the “greatest challenge to our country right now,” and has a meeting on Covid every day, according to the senior defense official.

One day after his swearing-in, Austin instructed the services to come up with measures to address sexual assault, giving them two weeks to deliver a summary of the ones that had worked and those that failed. He also threw his full support behind President Joe Biden’s repeal of the transgender ban, saying the armed services should welcome the “best possible talent in our population, regardless of gender identity.”

But his most dramatic move was on extremism, where Austin gave the military branches 60 days to pause and review the issue. He wants leaders of each branch to give clear guidance on how troops should behave, as well as to “gain insight” from members on the “scope of the problem from their view,” Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said Wednesday.

At his confirmation hearing, Austin acknowledged the task ahead. “I don’t think this is a thing that you can put a Band-Aid on and leave alone, he said. “I think that training needs to go on routinely.”

One senior defense official said these are the issues that can be “corrosive” to a military force, eating away at the moral and ethical core of a unit, which is meant to bind it as a fighting force.

On Tuesday, Austin also dismissed hundreds of members of the Pentagon’s 40 or more advisory boards and committees, ordering a review of the structure and function of the groups. The move was largely motivated by the Trump administration stacking the boards with loyalists in its waning days.

None of these issues, besides the pandemic, were seen as pressing concerns when Austin was nominated in early December. But in the ensuing weeks, he quickly realized the challenges at home were going to be a major focus of his tenure.

“You immediately walk into a firestorm of things that you have to take care of,” said Eliot Cohen, dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a former member of the Defense Policy Board.

Austin has reversed traditional roles.

Austin’s priorities have also reversed the traditional roles of the secretary and deputy secretary of defense, where the former faces outward and the latter inward.

“Normally the deputy secretary is ‘Mr. or Ms. Inside,’ and a lot of that is procurement and acquisition and that sort of things,” Cohen said. “Of course, he carries particular heft as a retired four-star [general], so it may be easier for him to simply push through those changes.”

His priorities are a function of his experience as a commander as he deals with the key issues of the time, analysts said, driving the 67-year-old retired general to tackle issues at home first. In addition, a difficult transition between administrations hampered his ability to get caught up quickly on the challenges facing the department.

“His first days at the Pentagon are basically trying to clean up from a lot of what Trump left there,” said former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, who spoke on behalf of Austin at his confirmation hearing. “It’s been a learning process to understand what’s taken place, what damage has been done, to make sure that you’ve got the right people and you’ve got the right policies in place for the Biden administration.”

During his confirmation hearing, Austin called China “the most significant challenge going forward,” adding that Russia, though “in decline,” was also a challenge. But he has no foreign trips on the agenda right now, and none are expected before April at the earliest because of the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2015, then-Secretary of Defense Ash Carter flew to Kuwait and Afghanistan in his first week. In 2017, James Mattis, confirmed as President Donald Trump’s first secretary of defense on the day of the inauguration, traveled abroad in his second week on the job, visiting Japan and South Korea. Two years later, Mark Esper flew to Europe to meet with NATO in his first week as acting secretary, even before he was confirmed.

The first time Austin met troops in the field as secretary of defense was not at an overseas base but near the Capitol, where he visited National Guardsmen.

“We know it’s not easy to leave home and come out here and help us out, but you’re doing a great service on behalf of your country,” Austin told the Guardsmen. In a sign of just how different the military he inherited truly is, in the wake of the Capitol riot there are now more US troops stationed in Washington than there are in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

Austin dealing with issues that are ‘familiar to him’

Eric Edelman, who was under secretary of defense for policy under President George W. Bush, said Austin’s focus “makes perfect sense.”

“Some of these issues are ones that Austin is going to feel a little more comfortable in dealing with because they’re familiar to him,” Edelman said.

Austin was a lieutenant colonel with the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 1995 when two neo-Nazi skinheads from the elite unit murdered a Black man and a Black woman in a racially charged killing. Austin, the country’s first Black defense secretary, brought up the events in his confirmation hearing.

“We discovered that the signs for that activity were there all along. We just didn’t know what to look for, what to pay attention to, what we learned from it,” Austin said, “and I think this is one of those things that’s important to our military to make sure that we keep a handle on.”

“We can never take our hands off the wheel on this.”

A quarter-century later, the problem has metastasized. At least 22 of those charged in connection with the Capitol riot of January 6 are current or former service members, according to a CNN review of the charges. The Department of Defense already has one review in place from former acting Secretary of Defense Chris Miller of policies, laws and regulations on extremism and hate group activity as part of its work on diversity and inclusion, which will also entail recommendations to update the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Austin is expected to take his own actions to address the issue, though the form of his instruction remains unclear.

“The disproportionate number of active-duty and former service members who have been arrested in the Capitol riot is really very worrisome,” said Edelman.

Austin’s current prioritization of sexual assault and extremism in the military is also a consequence of the issues being focused on across the country, said Richard Betts, a professor of war and peace studies at Columbia University.

“All of the attention to previously tolerated or semi-ignored or swept-under-the-rug sorts of issues has just bubbled up through society, and the military as a major institution has been caught up in it like others,” Betts said

But his inward focus does not mean Austin is oblivious to the challenges posed by the country’s adversaries.

He spent 41 years in the military, culminating in his leadership of US Central Command as a four-star general, which placed him in charge of US forces in the Middle East. But his career left him without any substantial time or experience in the Western Pacific, where an increasingly assertive China has pushed its presence wider and farther.

Austin will need his team to confront the challenge from Beijing, but much of it has not yet been put in place. There are 61 confirmed or appointed positions at the Pentagon, and as of last week, the vast majority of those positions were filled with either acting officials or “performing the duties of,” a defense official told CNN. Kathleen Hicks, the nominee for deputy secretary of defense, is widely expected to be confirmed soon, but that still leaves Austin without key support

“Given the fact that he’s ‘home alone’ right now — no one else has been confirmed — it’s not altogether surprising that this would be his focus,” Edelman said, referring to the domestic policies Austin has so far prioritized.

But Betts notes that Austin’s focus on domestic problems means he’s in step with the country at large.

“It’s only a small part of the public that really pays attention to the department’s outward mission,” he said.

Though Betts stressed that one mission does not preclude the other; the Pentagon must be able to look inward and outward at the same time. “You have to be attentive to your mission, but you have to be capable of and organized for and organizationally strong enough to do the mission.”