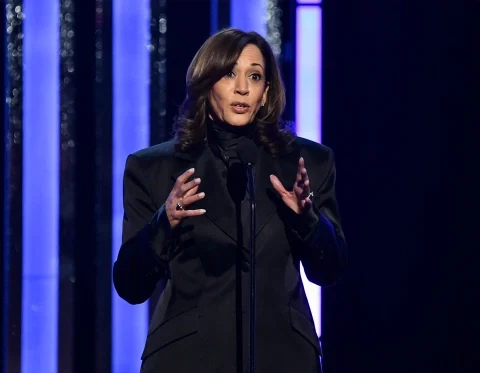

Nikki Buskirk was watching vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris and her husband Doug Emhoff wave to supporters at an Election Night celebration in November when the future second gentleman did something that made Buskirk glow with admiration.

The couple had just taken the stage in downtown Wilmington, Delaware, when red, white, and blue fireworks suddenly exploded in the evening sky. Buskirk says she watched as Emhoff instinctively stepped toward Harris to protect her.

That gesture touched Buskirk because her marriage had set off some fireworks of its own. She’s a proud Black woman and Black Lives Matter activist who had violated an unwritten rule in the Black community — thou shalt not date or marry White men.

The Ohio woman had been told all her life she was supposed to marry a strong Black man and build a strong Black family. But then she met Tyler Buskirk, a self-assured White man who shared her love of “The Phantom of the Opera” and Dungeons & Dragons. Their marriage shocked some members of both of their families, and Buskirk says she’s gotten plenty of icy, “how-could-you?” stares from Black women and men in public.

Seeing Emhoff rush to protect Harris, though, reminded her not of what she’s endured but what she’s gained — a man who is ready to defend her, no matter what comes their way.

“He’s my rock to come home to after fighting the world, my shield when it becomes too much, and my crusader when I can’t get through,” says Buskirk, 37. The pair live in Columbus, Ohio, where she works in a ministry at a local United Methodist Church.

“When I see Vice President Harris and her husband, I see us.”

Will more Black women begin to see the same potential for romantic love with White men? Harris’ next four years in the White House could help provide an answer.

The power of Harris’ example

Harris is the first female, Black and South Asian vice president of the United States, but she could also become another type of pioneer. She could inspire some Black women to reexamine a racial taboo that has shaped many of their private lives.

Harris has so far shared few private details about her marriage to Emhoff, a lawyer. They were set up on a blind date in 2013, when Harris was California’s attorney general, and married a year later.

Harris did briefly respond to criticism of her marriage to a White man in a 2019 radio interview.

“Look, I love my husband, and he happened to be the one that I chose to marry, because I love him — and that was that moment in time, and that’s it,” Harris said. “And he loves me.”

As President Barack Obama’s mere presence in the White House provoked discussions on biracial identity and Black marriage, Harris’ marriage could lead more Black women to talk openly about this taboo, one scholar says.

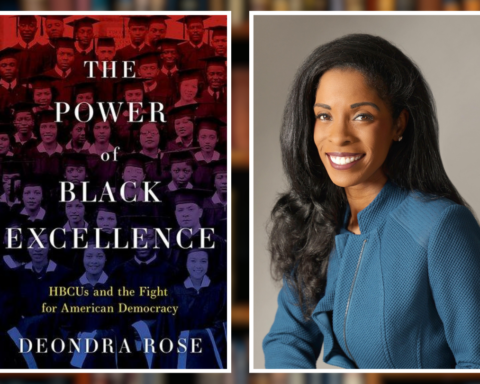

“I think there is potential, but it depends on how public or private she is about her marriage,” says Dianne M. Stewart, author of “Black Women, Black Love: America’s War on African American Marriage.”

“If she decides to talk about this aspect of her life and enters conversations about it or allows the broader public to have information about her own journey, it could influence Black women’s thinking,” says Stewart, an associate professor of religion and African American studies at Emory University in Atlanta.

She could even change long-held views in the Black community. One White House predecessor might even serve as a role model. Obama helped shift support for same-sex marriage among African Americans when he became the first President to say same-sex couples should be allowed to get married.

Why some Black women won’t marry White men

Many Black women have traditionally shunned White men for a variety of reasons. Some say they can’t be with a White man because he wouldn’t understand what it’s like to experience racism. Others say they owe it to their race to marry Black men and build healthy Black families.

Yet other Black women cite more personal reasons for staying away from White men. They say being with a White man evokes memories of how White plantation owners and others sexually abused Black women during slavery and colonization. They’re afraid of being treated as hypersexualized caricatures. (Some Asian women are wary of being with White men for some of the same reasons as Black women.)

“I haven’t completely reached the point where I can confidently order an Oreo ice cream swirl without some White guy telling me it ‘looks like us,’ but regardless of the number of ‘I love the color of your skin’ and ‘cream to your coffee’ messages that flood my DMs, determining whether a man is fetishizing me or not is not up to the discretion of White people,” Kendall Tiarra wrote in a recent essay titled, “Am I a Fetish or Just the Prettiest Girl in the Room?”

Some Black women reduce their reluctance to dating White men to one thought — it’s too much work. For example, they don’t want to expend energy teaching White men about racism or dealing with derogatory comments from friends, family and others.

Shamontiel L. Vaughn, a writer and editor, says she’s open to dating White men, but 90% of the men she has dated are Black. She published an essay last year, “Dating Black women: interracial dating gone right and wrong,” in which she explained why so many Black women shun dating White men.

Vaughn described what she and other Black women experienced on interracial dates: non-Black men who fetishized their bodies, raised the topic of race when it wasn’t necessary, or tried too hard “to copy every single element of Black men” because they “watched too much BET.”

When Vaughn dates White men, she chooses those who have dated Black women before. She cites one White man she dated who “was just cool.”

“By the time he met me, he had dated a bunch of Black women. It wasn’t new to him — like me putting a hair wrap on my head was no big deal,” she says. “He didn’t ask what it was. He didn’t ask why I oiled my hair. He had already been broken in.”

Nikki Buskirk is familiar with many of these arguments. She once believed some of them. She says some in her family raised her with the expectation that she would marry a Black man because such unions helped build strong Black families and strengthened their race.

Some of them objected to her dating Tyler and thought she was going through a phase. She experienced some nagging guilt at the time but overcame it.

They’ve now been married for 17 years and have three sons, ages 10, 7 and 3.

“He treats me like a queen,” she says. “I can’t let guilt ruin the love we have and the love we built.”

Some argue Black women should ‘lower their standards’

Reservations about dating or marrying across races may seem like a relic from the past. Interracial marriage has steadily become more common in the US since the Supreme Court ruled in the 1967 Loving v. Virginia decision that laws banning such unions were unconstitutional.

In 2015, one in 10 married people in the US had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, according to a Pew Research Center study. Popular culture is filled with images of couples such as Prince Harry and his bride Meghan Markle or tennis star Serena Williams with husband Alexis Ohanian.

But look closer at the lives of some Black women and the picture looks different. Many Black women seem trapped in a time warp where dating or marrying a White man is still rare. The same Pew report said Black men are twice as likely as Black women to have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity. Some people try to nudge Black women into the interracial dating pool by citing a 2010 census statistic that found an estimated 71% of Black women between the ages of 25 to 29 had never been married.

This historical reluctance to be with White men has generated a stream of articles, books, and talk show segments. One law professor wrote a book arguing that more Black women should “not marry down but out” — in other words, consider marrying non-Black men instead of settling for Black men who don’t meet their standards.

Yet there are some Black women who don’t want to compromise. As Stewart notes in her book, they are inspired by examples such as Michelle Obama’s marriage and they want what she seems to have — a Black man they can respect and love.

The wait for such a man, though, can be excruciating.

Stewart cites a single Black woman who confessed she was emotionally exhausted from living without Black male company.

“She just wanted Black male energy and presence in her life in some way,” Stewart wrote. “She told me that she could go an entire week, even several weeks, without having a substantive conversation with a Black man who was not her brother.”

Reinforcing racist assumptions?

It’s easy to cite Harris’ marriage as an inspirational model for all people who say color doesn’t matter. But color does matter to some.

Consider colorism — the notion that a person’s value and beauty is determined by the lightness of their skin.

Harris is a fair-complexioned woman, Stewart notes. She cites a 2009 study that showed that young Black women who are fair complexioned were twice as likely to have married by age 29 than darker-skinned Black women. Colorism is a complex issue that spills into many areas of Black life, not just interracial marriage.

Still, some darker-skinned Black women could look at Harris’ marriage and take a different message about their own self-worth by concluding, “that could never be me.”

Stewart takes this issue head-on in her book. She writes that as more Black women pay attention to women like Harris, more “will likely transgress cultural prohibitions” and try to date a wider pool of racially and ethnically diverse men.

Harris’ marriage could unwittingly reinforce another racist assumption: White men are the best potential marriage partners, while Black men are among the worst.

“There is a conversation out there in social media now that goes something like this: Black women should just open themselves up to men outside their race,” Stewart says. “And the default men that a number of these social media influencers have in mind are White men.”

The attention paid to Harris’ marriage could also distract people from addressing another huge issue: the precarious state of Black marriage, Stewart says.

Stewart contends in her book that White supremacy has waged a systematic assault against Black marriage for 400 years. This attack has taken different forms: slavery, White standards of beauty, and mass incarceration, which removes Black men from the pool of potential partners.

Many Black women are single today not because something is wrong with them, Stewart says. Instead, she says, their status is the result of a web of policies, customs and raw racism that make Black marriage “difficult, delayed or impossible.”

Stewart says she’s not opposed to interracial unions. But she’s concerned that encouraging Black women to marry non-Black men distracts people from addressing what many see as a crisis of Black marriage and romantic relationships.

“I don’t want to solve this problem by ignoring it and asking Black women to marry outside their race,” she says.

Harris’ marriage could inspire change

Nikki Buskirk has heard the arguments that White men can’t understand what it’s like for Black women to experience racism. She reframes the argument: Can any guy understand?

“I can say that about any guy,” she says. “A Black guy might not understand what it means to be a Black woman. Black women are the lowest of the lows when it comes to the hierarchy in America.”

Buskirk says she hopes Black women who are leery of dating White men pay attention to how Emhoff treats Harris.

“They could be missing out on something great if they let skin color stop them,” she says.

This country’s history, though, is filled with examples of how people have allowed skin color to blind them to other people’s humanity. And interracial relationships can provoke all sorts of strong and conflicting emotions. When some people see a Black and White couple, they don’t see two individuals — they see a projection of their own racial myths, insecurities and fantasies.

Buskirk’s reaction to Emhoff’s chivalrous Election Night gesture evoked the symbolic power of Barack Obama’s presidency, when seemingly throwaway moments — the President breaking into “Amazing Grace” at a funeral, Michelle Obama dancing with schoolchildren — elicited deep affection in Black Americans.

Harris could do the same. Her marriage to Emhoff could inspire Black women to think anew about their dating and marital choices.

That may depend, though, on whether Harris is willing to talk more about the delicate issues that swirl around her marriage.

And whether a nation that is still so divided by race and skin color is ready to listen.