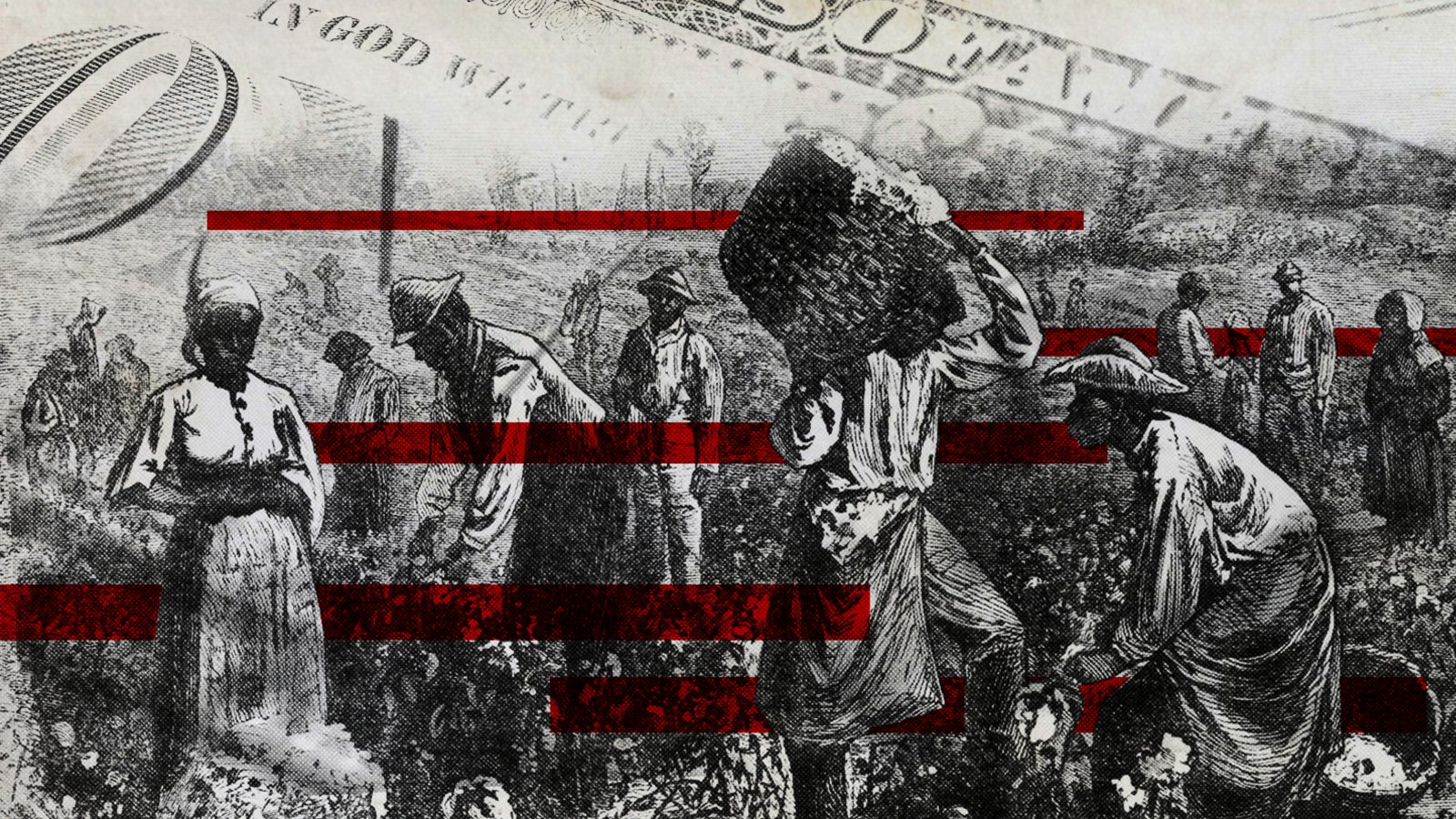

Slavery reparations are back in the national spotlight.

A House Judiciary subcommittee held a hearing this week to discuss establishing a federal commission that would explore how the US government might compensate the descendants of enslaved Americans.

And though the White House press secretary declined to say whether President Joe Biden would sign legislation to develop reparations for slavery, she did say he supported a study on the matter.

Lawmakers have been advocating for a federal effort to study slavery reparations for more than 30 years now — to no avail.

But since the widespread protests last year against racial injustice and the inequalities laid bare by the Covid-19 pandemic, the debate has taken on a new urgency.

“At the very root of the word reparation is the word repair,” Dreisen Heath, researcher and advocate for Human Rights Watch who testified at Wednesday’s hearing, told CNN. “And the necessary process of repair is the only way we get to actually achieving racial justice.”

So, just how would reparations, focused specifically on slavery, work?

Why are we talking about reparations again?

The idea of giving Black people reparations for slavery dates back to right after the end of the Civil War (think 40 acres and a mule). But for decades, it was mostly an idea debated outside the mainstream of American political thought.

That changed when writer Ta-Nahisi Coates published his 2014 piece in The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations.”In the years since, political leaders and members of the public have begun to take the issue more seriously.

The most recent movement on the topic came this week, when the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties heard testimony on a piece of legislation known as HR 40.

The bill proposes the creation of a federal commission to study reparations and recommend remedies for the harm caused by slavery and the discriminatory policies that followed abolition. That commission would also consider how the US would formally apologize for the institution of slavery.

HR 40 has been repeatedly introduced in Congress since 1989, though it has never passed.

“Now more than ever, the facts and circumstances facing our nation demonstrate the importance of HR 40 and the necessity of placing our nation on the path to reparative justice,” Rep. Shelia Jackson Lee, the lead sponsor of the bill, said at the hearing.

Lawmakers heard testimony from several people who spoke about why reparations were necessary for the nation to heal from slavery. Witnesses and experts pointed to how the concept had been applied internationally, as Germany did for the Holocaust, and even at home, after the internment of Japanese Americans.

Crucially, the passage of HR 40 wouldn’t actually result in payouts to the descendants of enslaved Americans.

Rather, it would establish a group of appointed leaders to make recommendations on what compensation and other remedies to provide and how to go about doing so.

How do you put a cash value on hundreds of years of forced servitude?

This may be the most contested part.

Academics, lawyers and activists have given it a shot, though, and their estimates have ranged over the years from the billions to the quadrillions.

A study published last year in The Review of the Black Political Economy offered several different figures based on a variety of estimation methods.

Researchers looked at the Black-White wealth gap in 2018 and compared it to what slavery and discrimination were estimated to have cost the African American descendents of enslaved people.

A method that considers the value of “40 acres and a mule” puts the amount at about $12 trillion in 2018 dollars. Based on the value that enslavers placed on enslaved people, the number is about $13 trillion. Using lost wages, the cost is at $18.6 trillion. And another model that calculates the value of lost freedom puts the number at $35 trillion.

Those are conservative estimates, given that they are compounded by 3% interest, the authors note. At 6% interest, the numbers go as high as $16 quadrillion.

Also worth noting is that those totals only deal with the slavery that happened from the time of the country’s founding until the end of the Civil War. They don’t account for slavery during the colonial period or the decades of legalized segregation and discrimination against Black Americans that followed emancipation.

Where would the money come from?

When it comes to a national slavery reparations effort, scholars and advocates generally agree that the US government should pay — given that it enshrined, supported and protected the institution of slavery.

William Darity, professor of public policy at Duke University and co-author of “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century,” told Quartz last year that the government could draw the money against the national debt and paid for it by selling treasury bonds — similar to how the coronavirus stimulus checks operated.

“It can be done without creating new taxes,” he told the publication. “We embrace the principles of modern monetary theory. The only barrier to increasing federal spending is the potential adverse impact on inflation. To minimize inflation, we advocate doing it over 10 years.”

Similarly, state governments might pay for state-level slavery reparations efforts.

Advocates have also proposed having private businesses that financially benefited from slavery and rich families that owe a good portion of their wealth to slavery pay.

As you might imagine, suing large groups of people to pay for reparations might not go over well. Others have suggested lawmakers could pass legislation to force families to pay up. But that might not be constitutionally sound.

“I don’t think you can legislate and have those families pay,” Malik Edwards, a law professor at North Carolina Central University, told CNN in 2019. “If you’re going to go after individuals you’d have to come up with a theory to do it through litigation. At least on the federal level Congress doesn’t have the power to go after these folks. It just doesn’t fall within its Commerce Clause powers.”

The Commerce Clause refers to the section of the US Constitution which gives Congress the power to regulate commerce among the states.

But reparations mean more than a cash payout, right?

For many proponents, yes. Reparations could come in the form of special social programs or land resources. It could mean a mix of cash and programs targeted to help Black Americans.

Heath said that while financial payments are a key part of slavery reparations, the process should go beyond that.

“There’s more forms to reparations than just financial compensation, although we absolutely have to calculate and evaluate that,” she said. “But there also needs to be health care-specific reparations addressing psychological trauma and other mental harms, official truth-telling measures, official apologies for wrongdoing, institutional and legal reforms that challenge the current institutions that don’t serve to protect Black people today.”

Chuck Collins, an author and a program director at the Institute for Policy Studies, told CNN in 2019 that reparations could seek to address the discrimination Black people have experienced in home ownership or higher education.

“Direct benefits could include cash payments and subsidized home mortgages similar to those that built substantial White middle-class wealth after World War II, but targeted to those excluded or preyed upon by predatory lending,” he said at the time. “It could include free tuition and financial support at universities and colleges for first generation college students.”

Reparation funds could also be used to provide one-time endowments to start museums and historical exhibits on slavery, Collins said.

What are the arguments against reparations?

There are many. Opponents of reparations argue that all the slaves are dead, no White person living today owned slaves or that all the immigrants that have come to America since the Civil War don’t have anything to do with slavery. Also, not all Black people living in America today are descendants of enslaved people.

As reparations were debated in the House this week, Republicans argued that such proposals were “divisive” and that it would be “unfair to punish White Americans today for their ancestors’ mistakes.” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell opposed the idea in 2019, arguing “none of us currently living are responsible” for what he called America’s “original sin.”

Others point out that slavery makes it almost impossible for most African Americans to trace their lineage earlier than the Civil War, so how could they prove they descended from enslaved people?

Writer David Frum noted those and other potential obstacles in a 2014 piece for The Atlantic entitled “The Impossibility of Reparations,” which was a counterpoint to Coates’ essay. Frum warned that any reparations program would eventually be expanded to other groups, like Native Americans, and he feared that reparations could create their own brand of inequality.

“Within the target population, will all receive the same? Same per person, or same per family? Or will there be adjustment for need? How will need be measured?” asked Frum, a former speechwriter for President George W. Bush. “And if reparations were somehow delivered communally and collectively, disparities of wealth and power and political influence within Black America will become even more urgent. Simply put, when government spends money on complex programs, the people who provide the service usually end up with much more sway over the spending than the spending’s intended beneficiaries.”

Conservative activist Bob Woodson decried the idea of reparations as “yet another insult to Black America that is clothed in the trappings of social justice” in a column for The Hill in 2019. He also told CNN he feels America made up for slavery long ago, so reparations aren’t needed.

“I wish they could understand the futility of wasting time engaging in such a discussion when there are larger, more important challenges facing many in the Black community,” Woodson, the founder and president of the Woodson Center, said. “America atoned for the sin of slavery when they engaged in a civil war that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Let’s for the sake of argument say every Black person received $20,000. What would that accomplish?”

This isn’t the first time reparations have come up, is it?

After decades of languishing as something of a fringe idea, the call for reparations really caught steam in the late 1980s through the ’90s.

Former Democratic Rep. John Conyers first introduced HR 40 in 1989 to create a commission to study reparations. He would do so repeatedly until he left office in 2017. Texas Democratic Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee has since taken up the HR 40 baton.

Activist groups, like the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America and the Restitution Study Group, sprang up during this period. Books, like Randall Robinson’s “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” gained huge buzz.

Then came the lawsuit. In 2002, Deadria Farmer-Paellmann became the lead plaintiff in a federal class-action suit against a number of companies — including banks, insurance company Aetna and railroad firm CSX — seeking billions for reparations after Farmer-Paellmann linked the businesses to the slave trade.

She got the idea for the lawsuit as she examined old Aetna insurance policies and documented the insurer’s role in the 19th century in insuring slaves. The suit sought financial payments for the value of “stolen” labor and unjust enrichment and called for the companies to give up “illicit profits.”

“These are corporations that benefited from stealing people, from stealing labor, from forced breeding, from torture, from committing numerous horrendous acts, and there’s no reason why they should be able to hold onto assets they acquired through such horrendous acts,” Farmer-Paellmann said at the time.

The case was tossed out by a federal judge in 2005 because it was deemed that Farmer-Paellmann and the other plaintiffs didn’t have legal standing in the case, meaning they couldn’t prove a sufficient link to the corporations or prove how they were harmed. The judge also said the statute of limitations had long since passed. Appeals to the US 7th Circuit Court of Appeals and the US Supreme Court proved unsuccessful, and the push for reparations kind of petered out.

But Coates’ 2014 article in The Atlantic reignited interest in the issue. New reparations advocacy groups, like the United States Citizens Recovery Initiative Alliance Inc., took up the fight. Black Lives Matter includes slavery reparations in its list of proposals to improve the economic lives of Black Americans. Even a UN panel said the US should study reparations proposals.

So, what are the prospects of reparations moving forward?

Slavery reparations still face an uphill battle in Congress.

HR 40 would have to pass a vote by the House Judiciary Committee before it could receive a debate on the House floor.

Advocates are hopeful that the Democratic majority in Congress, the Biden administration’s support for a study on reparations and the renewed momentum around racial justice could allow HR 40 to finally move forward.

The bill has more than 160 co-sponsors in the House, and Speaker Nancy Pelosi has publicly backed the bill. But even if HR 40 passed the House, it would probably face a tougher time in the more narrowly divided Senate.

Still, as the nation continues to reckon with its past racial injustices, reparations are being explored at the state and local level, too.

California became the first state in the country last year to enact a law to study and develop proposals for slavery reparations. State lawmakers have started appointing leaders to the task force.

Several municipalities in North Carolina have passed reparations resolutions. Similar efforts have taken place in cities including Evanston, Illinois, and Providence, Rhode Island.

Whatever happens, more people finally seem to be recognizing that something needs to be done to address the disparities that slavery helped create.

“People are really starting to understand the legacy of slavery does exist and impact people a great deal,” Heath said. “It’s a moral and practical imperative for Congress to embark on the repair process for Black people. It can’t continue to stall any longer because the consequences continue to be compounded and the injuries worsened over time.”