A spacecraft named for the famed NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson has arrived at the International Space Station with about 8,000 pounds of cargo in tow.

The S.S. Katherine Johnson, a Northrop Grumman Cygnus resupply spacecraft, launched on Saturday from a NASA facility in Virginia and made it to the space station early Monday morning. It carries a massive amount of science and research, crew supplies and vehicle hardware that will assist researchers there in numerous investigations.

The spacecraft will support experiments that are exploring treatments to restore vision to those with retinal degenerative diseases, why astronauts experience muscle weakening in microgravity and how astronauts sleep in space, among others. It also brings advanced computing to the space station and upgrades to clean air and water systems for the crew there.

The S.S. Katherine Johnson will be at the International Space Station until May, when it will make its fiery journey back to Earth, disposing of several thousands of trash along the way, according to a news release.

That the spacecraft bears the name of Johnson, who also inspired the 2016 film “Hidden Figures,” is an “honor,” said Adi Boulos, the lead NASA flight director for the mission.

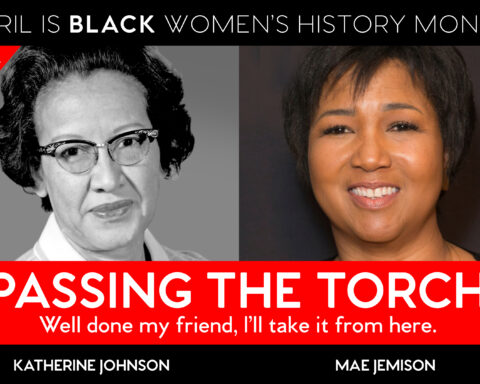

“As a Black woman, Katherine Johnson shattered race and gender barriers to live out her dreams and become a pivotal part of this country’s young space program,” he said in a statement.

“Fifty-nine years ago today, astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth after personally asking for Katherine Johnson to verify his Mercury missions’ orbital trajectory calculations. Katherine Johnson was an asset to our space program, and I am honored to work for a mission that expands her legacy even further.”

Johnson’s work made early space missions possible

Johnson died last year at age 101. Her work went largely unrecognized until the release of “Hidden Figures.”

The pioneering mathematician was part of NASA’s “Computer Pool,” a group of mathematicians whose data powered the agency’s first successful space missions.

Johnson got her start at NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and NASA’s predecessor, in 1953 — one of several Black researchers hired for the agency’s aeronautical lab after an executive order that prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry.

Johnson first began in the facility’s segregated wing for women before soon being transferred to the Flight Research Division, where she would work for several years.

Her career started to ramp up as the space race between the US and the Soviet Union did in the late ’50s. Johnson pushed her way into briefings traditionally attended only by men and secured a place in the inner circle of the American Space Program.

She was tasked with performing trajectory analysis for Alan Shepherd’s 1961 mission, the first American human spaceflight. She co-authored a paper on the safety of orbital landings in 1960 — the first time a woman in the Flight Research Division received credit for a report. Her work quickly garnered attention for its accuracy, and John Glenn would famously call on her to crunch the numbers for his spacecraft’s trajectory before his orbit around Earth.

Johnson’s work was also instrumental in mapping the moon’s surface ahead of the 1969 landing and played a role in the safe return of the Apollo 13 astronauts. She retired in 1986.