Ernest Fann never imagined his baseball career would be tainted by racism more than a decade after Jackie Robinson‘s debut.

“Somebody told me baseball was a White man’s game,” he says about a teammate who approached him while he sat on the bench. It was the early 1960s and Fann was playing for the Burlington Bees, a minor league affiliate of the Kansas City Athletics in Burlington, Iowa.

“That’s the biggest lie I’ve been told,” the 77-year-old added.

In the years after Robinson became the first Black player in Major League Baseball, racial progress in the sport was slow and the Negro Leagues, which had been a vibrant showcase of talent, soon collapsed. Fann and other Black baseball players were often facing racism in and outside the clubhouse.

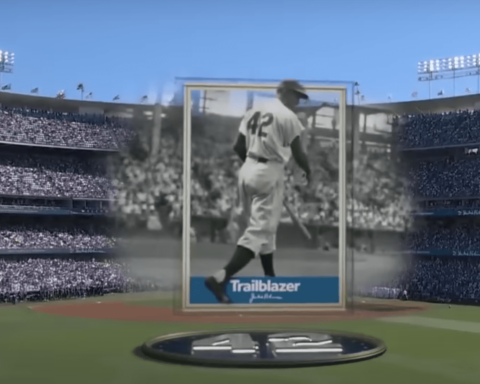

On Thursday, MLB is observing the day Robinson first played with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Commemoration of the day comes as the nation’s racial reckoning continues in the wake of the shooting of Daunte Wright. The MLB were among the sports leagues who postponed their Monday games in Minneapolis Monday, and New York Yankees center fielder Aaron Hicks took himself out of the lineup for Monday’s series opener in New York.

And while hundreds of players and coaches will sport Robinson’s iconic No. 42 on Thursday, other Black players want to ensure their stories are remembered as well.

During the first half of the 20th century, the major leagues of baseball were White only and Black owners formed their own leagues. Andrew “Rube” Foster was instrumental in the foundation of the Negro National League in 1920 and other leagues emerged over the years, including the Negro American League with teams from the Midwest.

Players in the Negro Leagues earned considerably less than their White counterparts and segregation made it difficult for teams to have their own ballparks or find hotels and restaurants while on the road. Robinson got his start with the Kansas City Monarchs, a team in the Negro National League, a few years before he broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Phil S. Dixon, a baseball historian and author of multiple books about the Negro Leagues, said major league teams slowly became integrated but racism and discrimination didn’t vanish.

“Even though they integrated baseball, they (players) were still dealing with the customs of American society, the institutionalized racism, Jim Crow, and just general oppression,” Dixon said. “Just putting a Black player on the team didn’t eliminate all have those barriers.”

After playing in the Negro Leagues with the Raleigh Tigers in the early 1960s, Fann joined the minor league system of the St. Louis Cardinals and the Kansas City A’s — where he says he learned baseball was not exempt of racism.

Fann grew up in an integrated neighborhood in Macon, Georgia, and saw Black and White children getting along and often playing stickball together. His baseball career is full of contrasting memories to those of his childhood.

Black players like him couldn’t eat at the same restaurant as their White teammates or stay in the same motel. He was also called a racial slur by a teammate, Fann recalled.

Fann retired after a knee injury and moved to Birmingham, Alabama, where he later played in the semiprofessional Industrial Baseball League while working as a forklift driver for 15 years.

Robinson and Hank Aaron got their start in the Negro League

Decades after Fann retired from baseball, he befriended a White teenage boy from a Boston suburb who collected sports memorabilia. The boy would later help many former Negro League players reunite over the years and gain recognition.

Cam Perron, now 26, wrote about his unlikely friendship with Fann and other former players for his new book “Comeback Season: My Unlikely Story of Friendship with the Greatest Living Negro League Baseball Players.”

As a teenager, Perron made it his mission to contact players as a way to collect autographs. While he didn’t have a strong sense of the history of systemic racism, he says, he realized the players had been treated unfairly and some were exploited by collectors in recent years.

Perron wrote letters to dozens of players that turned into phone calls and an annual reunion for players. Perron became friends with several former players, including Fann and Russell Patterson, who played with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues in 1960.

After playing a game in Huntsville, Alabama, Patterson told CNN that he and his teammates had to stay overnight and slept “with the bats on our chests because the Ku Klux Klan was supposed to have seen us playing that day.”

The players are not household names like Robinson or the late Hall of Fame baseball star Hank Aaron, Perron told CNN, but their experiences “paved the way for baseball now.”

Aaron wrote in the book’s foreword that the first professional baseball game that he saw was when the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues played in Mobile, Alabama, and inspired him to compete on a professional level.

When he turned 18, Aaron joined the team and soon broke into the majors, becoming the longtime home run king and one of the greatest baseball players of all time.

“Those months I spent on the Clowns helped me tremendously – not only teaching me how to play the game itself but also showing me that I belonged at that level. I’ll never forget that,” Aaron wrote.

Last year, Major League Baseball announced it would recognize the Negro Leagues as a major league and count the statistics and records of thousands of Black players as part of the game’s storied history. The announcement came during the centennial celebration of the founding of the Negro Leagues.

“All these years, these guys felt like they had to fight for somebody to even listen to them. They would say ‘I was a pro baseball player in the Negro League’ and people just did not really think that the Negro Leagues was a pro league,” said Perron, who now has his own memorabilia business.

For Dixon, the baseball historian, telling the history of the Negro Leagues and Black baseball players is key to the progress of the sport.

“There’s so many sacrifices that were made,” Dixon said. “I think that we just don’t realize what these men went through to make baseball what it is today.”