Lawmakers on Capitol Hill will juggle a slate of competing priorities this week as both parties wrestle with tense negotiations over infrastructure and police reform.

Deliberations will play out during a week set to be defined by President Joe Biden’s first address to a joint session of Congress on Wednesday, which will serve as a kind of call to action for lawmakers to meet the moment with bipartisan solutions for the country’s most pressing issues.

“It’s a basic question,” the President said last month in rolling out the first part of the package outlining his infrastructure goals. “Can democracies still deliver for their people?”

But a gap exists between Biden’s typically soaring rhetoric about unity and the reality of how a divided Congress operates. Stark disagreements exist on infrastructure, police reform and gun control — three big issues that Biden is calling on Congress to address.

Here’s where things stand on Capitol Hill:

An ‘active conversation’ taking place on infrastructure

GOP Sen. Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia told CNN’s Dana Bash on “State of the Union” Sunday that there’s been some “very encouraging” signs from the White House since Republicans unveiled their infrastructure counter proposal last week.

The GOP counter offer has a price tag in the neighborhood of $600 billion, focusing on roads, bridges and more traditional infrastructure. That’s much smaller than Biden’s roughly $2 trillion plan, which is expected to be paired with a similarly expensive “American Family Plan” to be unveiled this week.

Aides familiar with the Republican proposal point out it is meant to be an opening bid in a broader negotiation, not the final product. But $600 billion is far from the roughly $4 trillion proposals that the White House has floated and everyone acknowledges that significant concessions would have to be made on both sides to get anything that could pass in the middle.

Still, Capito maintained Sunday that an “active conversation” was taking place, and called her initial discussions with Democrats “a good beginning.”

“I think we have to look at the comparison of the two plans. We really narrowed the focus on infrastructure to really look at physical infrastructure: roads, bridges, rail, airports, water systems. The President’s bill of $2.2 trillion goes far afield from that,” she said.

“So where I think the first starting point we need to have is, let’s do an apples to apples comparison of the physical infrastructure, core infrastructure part of his plan and how it matches up with what we put forward. The President asked for our plan, and we thought it was really important to put a marker in, to show what we thought was important, what’s going to be the job-creating infrastructure plan, and how much it would be.”

“So I think we’re at a really — and all indications are it’s time to really start putting the pencils to the paper.”

But doing so would make a few things clear, like the discontent within the Democratic ranks about Biden’s push for a big plan that addresses far more than just roads and bridges.

Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin, who wields significant influence in the Senate as a result of his party’s slim majority, made that much clear once again Sunday morning. He told Bash that he supports a “more targeted” version of Biden’s plan while flexing his potential veto power in the negotiations over the package.

“I do think they should be separated,” Manchin said. “Because when you start putting so much into one bill, which we call an omnibus, it makes it very, very difficult for the public to understand.”

“The human infrastructure is something that we’re very much concerned about, and when you think about all that we have done in the last year and plus the Covid bill this year, the American Rescue Plan, an awful lot has been done there, too,” the West Virginia Democrat added.

The so called “human infrastructure” prong of Biden’s plan will come into clearer focus this week. The sweeping proposal will be centered around child care, paid family leave, education funding like free community college tuition and other domestic priorities.

A collection of Democratic senators from a broad ideological spectrum are also asking the President to make sure the proposal includes improvements to the health care system.

In a letter obtained by CNN, 17 senators specifically ask for Biden to lower the Medicare eligibility age, expand Medicare benefits to include hearing, dental, and vision care, implement a cap on out-of-pocket expenses under traditional Medicare, and allow the program to negotiate lower drug prices.

Outside of Congress, a new NBC News national poll found considerable support for Biden’s infrastructure plan: 59% said his proposal is a good idea, 21% disagreed while 19% didn’t have an opinion.

Progressives push back on police reform compromise

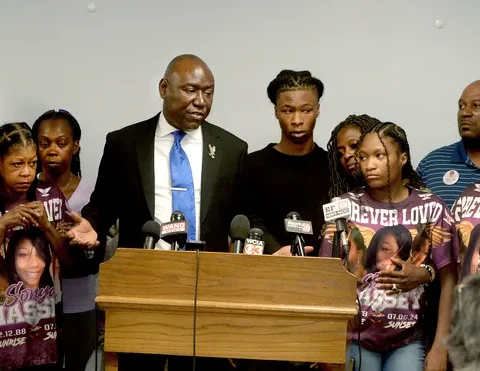

Both Democrats and Republicans said Sunday that they see hope for a compromise on the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which has found new momentum in the wake of former Minneapolis Police officer Derek Chauvin’s conviction.

The legislation, which passed the House but faces an uncertain future in the Senate, would set up a national registry of police misconduct to stop officers from evading consequences for their actions by moving to other jurisdictions.

It would ban racial and religious profiling by law enforcement at the federal, state and local levels, and it would overhaul qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that critics say shields law enforcement from accountability.

Last week, Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina floated a potential compromise on reforming qualified immunity, and has said some Democrats he has spoken with are open to it and that he doesn’t believe Republicans are far apart on the issues.

GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina similarly said Sunday that he believes there is a way to find compromise on qualified immunity.

“We can solve the issues if there’s will to get there, and I think there’s will to get there on the part of both parties now,” Graham told Fox News’ Chris Wallace on “Fox News Sunday.”

But progressives have made clear that it’s not that simple.

“I don’t know if I’m willing to blow up the deal, I don’t consider that blowing it up, but we do have to look at ways,” Rep. Karen Bass, a California Democrat who is leading the negotiations with Scott, told Fox News when asked if she would blow up the deal if she couldn’t reach a middle ground with Republicans on qualified immunity.

“Now, if Lindsey Graham and Tim Scott can show us some other way to hold officers accountable, because this has been going on for just decades.”

Democratic Rep. Cori Bush of Missouri, meanwhile, said she would refuse to vote for new policing reform legislation that compromises on civil lawsuit protections currently afforded to police officers.

“We compromise on so much. You know, we compromise, we die. We compromise, we die,” Bush told CNN’s Abby Phillip on “Inside Politics” when asked about a deal on qualified immunity.

“I didn’t come to Congress to compromise on what could keep us alive. … If you don’t hurt people, if you don’t kill people, if you are just and fair in your work, then do you need the qualified immunity anyway?”

Enter Joe Biden

The President had been formally invited to speak to Congress this Wednesday by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who wrote in a letter earlier this month that she was extending the invitation so he could “share your vision for addressing the challenges and opportunities of this historic moment.”

Putting some wind in the sails of infrastructure and police reform negotiations will likely be a priority, but the coronavirus will still serve as a conspicuous backdrop.

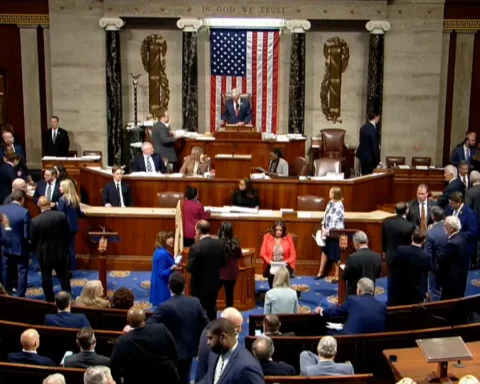

The joint session will be designated a National Special Security Event and there will be a limit on the number of lawmakers in the House chamber due to Covid-19 protocols, a Capitol official involved in planning previously told CNN.

Lawmakers will also be seated in the upstairs gallery in addition to the House floor, and guests will not be permitted.

Pelosi, a California Democrat, had said earlier this month that she was waiting to make a decision on extending an invitation to Biden amid concerns over the coronavirus pandemic, noting that it would come in consultation with the Capitol attending physician.

Former President Donald Trump’s final State of the Union address was delivered just before the pandemic took hold in the US, and his first address to a joint session of Congress was given in late February 2017. Former President Barack Obama, meanwhile, gave his first presidential address to a joint session in February 2009.