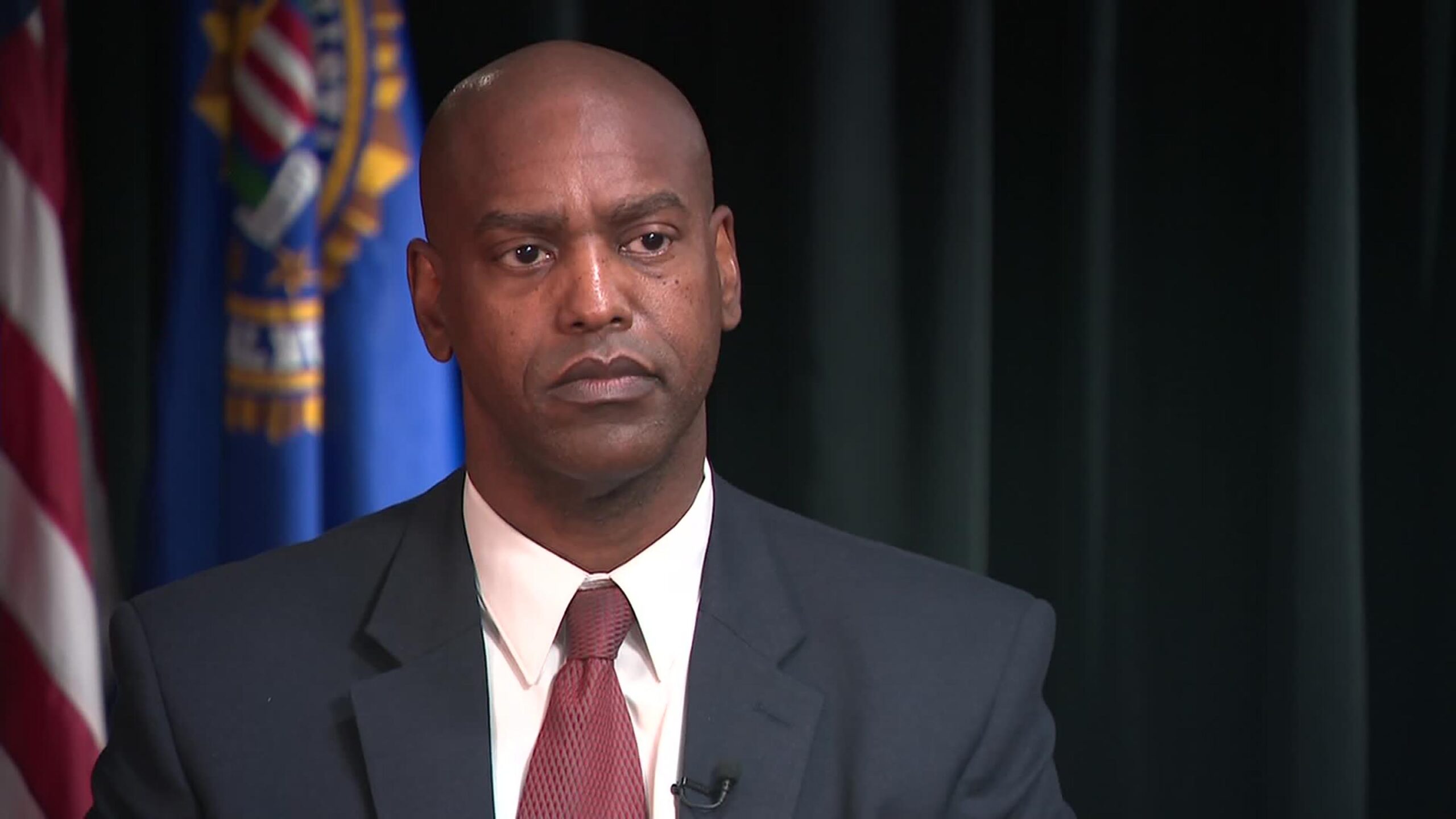

The Federal Bureau of Investigation just unveiled a newly created position to tackle its decades-old diversity problem: chief diversity officer.

Scott McMillion is a 23-year veteran of the FBI who is stepping into the role at a time when racial tensions have boiled over nationwide, with the FBI taking the lead in a growing number of civil rights investigations. Its Charlotte office launched a probe into the police shooting death of Andrew Brown Jr.; its Louisville office is investigating Breonna Taylor’s death in the wake of a botched police raid; and the FBI has partnered with the Wisconsin Division of Criminal Investigation to probe the shooting of Jacob Blake, which left him paralyzed.

The investigations will inevitably be conducted by a majority White workforce — 74% of FBI employees are White, according to the Office of Personnel Management. And just 4.7% of the roughly 13,500 special agents at the FBI identify as Black or African American, the agency says.

McMillion insists the racial makeup of the investigative teams won’t affect the outcome, but he acknowledges that stronger relationships with communities of color are possible only if the FBI diversifies.

“It is good to have diversity among the ranks because it does bring trust,” McMillion said. “But those agents who show up, regardless of what they look like or what their race or ethnic makeup may be, they’re going to do the best job, they’re going to follow the process and the facts that take us to where the evidence is.”

Black communities, in particular, have historically viewed the FBI with suspicion, and the fraught relationship is punctuated by the FBI’s counterintelligence surveillance of prominent civil rights leaders in the 1950s and 1960s, most notably, Martin Luther King Jr.

“We own the mistakes and even the things of the past that have happened,” McMillion said. “We don’t steer clear of that or shy of that, we recognize that. And the bottom line is we’re going to do better.”

Yet while the FBI’s new chief diversity officer position is historic, it reports to the associate deputy director, not FBI Director Christopher Wray, a personnel structure that diversity advocates have criticized.

McMillion officially became chief diversity officer on May 4, moving to the FBI’s headquarters in Washington from the Columbia, South Carolina, field office where he was assistant special agent in charge. McMillion’s main mission so far has been to foster community outreach and to emphasize to people in communities of color that the FBI needs people like them. Under McMillion’s leadership, the FBI has targeted potential minority candidates via social media, organized community engagement events in cities like Chicago and reached out to women’s organizations.

“We’re reaching out to those underserved communities who haven’t ever considered the FBI for a career or a job,” McMillion said. “That community engagement speaks volumes, particularly when we go to certain communities to say that we are actually looking for people who look like them to serve in the FBI because we know that brings credibility to us.”

McMillion started his career at the FBI in 1998 as a special agent in Omaha, Nebraska, where he says he was the only Black agent in all of Nebraska plus the neighboring state of Iowa.

“But I didn’t feel isolated,” McMillion said. “I felt the compliment of other people around the country as well as my cohorts within the office that made me feel welcome even as a Black man.”

That sentiment isn’t often shared by the small percentage of Black special agents working for the FBI each year.

“I felt alone a lot,” said Eric Jackson, a retired special agent in charge for the FBI’s Dallas field office.

Diversity concerns

Jackson was the only Black special agent in training in his FBI Academy class in 1997. When he started work at his first field office, in Tampa, Florida, he was mentored by James Barrow, who shared his own story about being one of the first African Americans to join the FBI.

“That gave me pause, to think that there are people who have gone through a lot prior to me and they survived, and that I was going to survive,” Jackson recounted in a video posted by the FBI several years ago celebrating “100 Years of African American Special Agents.”

But Jackson is concerned by the numbers; he says the percentage of Black special agents has declined in recent years. “The Black agent numbers have never gotten above 6%,” Jackson said. “That should concern everyone, especially when our population is anywhere from 12 to 14%.”

In fact, according to the Office of Personnel Management, the percentage of Black or African American employees at the FBI has dropped from 12% in 2016 to 10.7% in 2021. However, minority representation overall at the FBI has slightly improved in the past five years, from about 24.4% in 2016 to approximately 25.8% in 2021.

Jackson is now co-chairman of the MIRROR Project, an organization of retired Black special agents who are voicing their diversity concerns to the top leadership at the FBI.

“We should resemble the community we serve,” Jackson said. “As a Black male special agent in charge of the 12th largest division of the FBI, I was able to get into communities that didn’t want to have anything to do with law enforcement. But they wanted to hear what the first Black special agent in charge in the Dallas division had to say, so they gave me a chance. That really matters. If you have a diverse workforce you’re able to serve the diverse community.”

Members of the MIRROR Project say they have met at least twice with Wray in recent months, and they largely applaud the creation of the chief diversity officer position.

“We have put a lot of pressure on the FBI,” Jackson said. “And I can tell you that there have been collegial meetings to more tense meetings, but without a shadow of a doubt they are taking this seriously.”

Jackson and others within the MIRROR Project, however, are dissatisfied with the way the position has been structured. McMillion answers to Associate Deputy Director Jeffrey Sallet and does not have a direct line to Wray.

“We believe by not having this position in direct access to the FBI director that things will get filtered before they get to the FBI director,” Jackson said. “You run the risk of that position failing or being marginalized when different leadership is brought in.”

Rhonda Glover Reese, a former Black special agent who retired in 2018 after 34 years, put it a lot more bluntly.

“His role right now doesn’t have any juice,” Reese said. “He needs to be right there with the director.”

McMillion, though, said he is satisfied with the way his role is positioned and the access he gets.

“When you look to where I report, which is the associate deputy director, that is just two levels below the director,” McMillion said. “The director can’t be everywhere at one time. And so [the associate deputy director] reports directly to the director, so I have that streamlined approach right to him.”

Desire for Wray to speak up

Members of the MIRROR Project have also voiced frustration that Wray has not made a more public pronouncement pledging a commitment to diversity at the FBI. Wray touched on the subject during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in March, rejecting the premise that the FBI is a “systemically racist institution” when questioned by Republican Sen. John Kennedy of Louisiana. Wray also acknowledged that the FBI needed to improve its hiring practices.

“I do believe the FBI has to be more diverse and more inclusive than it is, and that we need to work a lot harder at that and we’re trying to work a lot harder at that,” Wray said.

Some members of the MIRROR Project say they want a more robust statement from Wray, especially now that McMillion has taken over as chief diversity officer.

“We just haven’t heard anything,” said Reese. “We’ve urged the director to put out some sort of statement to make sure the rank and file and all employees know that this new position is important.”

Wray did put out a statement announcing McMillion’s hiring in April, saying, “Scott is the right person to ensure that the FBI fosters a culture of diversity and inclusion, and that our workforce reflects all the communities we serve.”

But Michael Mason, who is also a member of the MIRROR Project and eventually rose to the rank of executive assistant director at FBI headquarters before retiring in 2007, says there’s more that Wray needs to do.

“I would certainly like to see him make a personal commitment to diversifying the FBI,” Mason said. “He should say that he intends to leave the FBI more diversified than it was when he came in.”

McMillion has responded to the concerns, defending Wray’s commitment to diversity.

“The senior leadership at the FBI, to include Director Wray, are very much committed personally to the mission of diversity, equity and inclusion,” McMillion said. “Director Wray takes every opportunity that he can to support and mention diversity, particularly to the inside workforce, and every time he goes out externally.”

The FBI points to statistics that show signs of improvement. The number of minority special agent applications has increased recently, with minorities representing 47% of applicants in fiscal year 2021. Plus, the bureau notes that the percentage of new Black agents training at its academy in Quantico over the past six years has doubled from 4% in fiscal year 2014 to 8% in fiscal year 2020.

Wray has also named minorities and women to several high-profile positions at FBI headquarters and in prominent field offices. Four new minority or female executive assistant directors were recently named to oversee divisions at headquarters: Larissa Knapp, an Asian American woman who oversees the human resources branch; Mo Myers, a Black man who oversees the intelligence branch; Brian Turner, a Black man who oversees the Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch; and Jill Sanborn, a woman who oversees the National Security Branch.

In all, 10% of the most senior executives in the FBI are Black, according to the FBI. Wray also promoted Emmerson Buie Jr. in September 2019 to become the first Black agent to lead the FBI’s Chicago field office, and 17 of the special agents in charge leading the FBI’s 56 field offices are minorities.

The slow change to incorporate more minorities into the FBI likely won’t immediately impact the civil rights investigations moving forward after the spate of recent police shootings. But the recently renewed focus on diversity could enhance community support for, and cooperation with, the FBI in the future. Jackson says it’s about gaining trust in the long term from minority communities.

“When I became an FBI agent and I raised my hand, it was to protect this great nation from enemies, both foreign and domestic,” Jackson said. “To be able to do that, you have to be able to not only reach the community but you have to win the community’s trust. If the community doesn’t trust you they’re not going to bring their issues to you, they’re not going to look at your motives as honorable. They’re going to question you. Especially people in the Black community. They are questioning law enforcement at every level, at every agency.”

McMillion stressed that the relatively low percentage of Black agents currently at the FBI will not affect the federal investigations into police conduct but that the statistics do highlight the importance of his newly assumed mission.

“It is good to have diversity among the ranks because it does bring trust,” McMillion said. “But I want to make sure people know that no matter who shows up within the ranks of the FBI, they are going to do the best job for the community they’re serving because that’s what they’re sworn to do.”