Lakiea Bailey has tried to hide the pain and breathlessness she feels from her disease for most of her life.

As a child, she missed weeks out of every school year because of sickle cell — a painful, genetic disease that’s believed to impact 100,000 Americans.

Patients’ red blood cells are “sickle” shaped and can clump together to impede blood flow to the rest of the body, causing serious problems, including strokes and organ failure.

As a studious young woman yearning to be normal, she hid her condition from her professors when she went off to college. But she says it only made her life harder.

When the condition flares up, an event known as a sickle cell crisis, “you cannot move, you can barely breathe without intense full-body pain in some cases, or it might simply be two arms, one leg, a foot,” the 42-year-old told CNN.

Bailey has endured hundreds of surgical procedures, blood transfusions and hospitalizations over her lifetime. She remembers, as a child, fearing the night because that’s when her sickle cell crises most often hit.

“I thought there was something about the hours between 2 and 5 a.m. that was just dangerous,” she said.

From patient to doctorate

Bailey’s mother told her that because she was sick she always had to work hard to get ahead.

“I often studied during breaks, and I enjoyed it,” she said. “I was a huge nerd that read medical dictionaries for fun.”

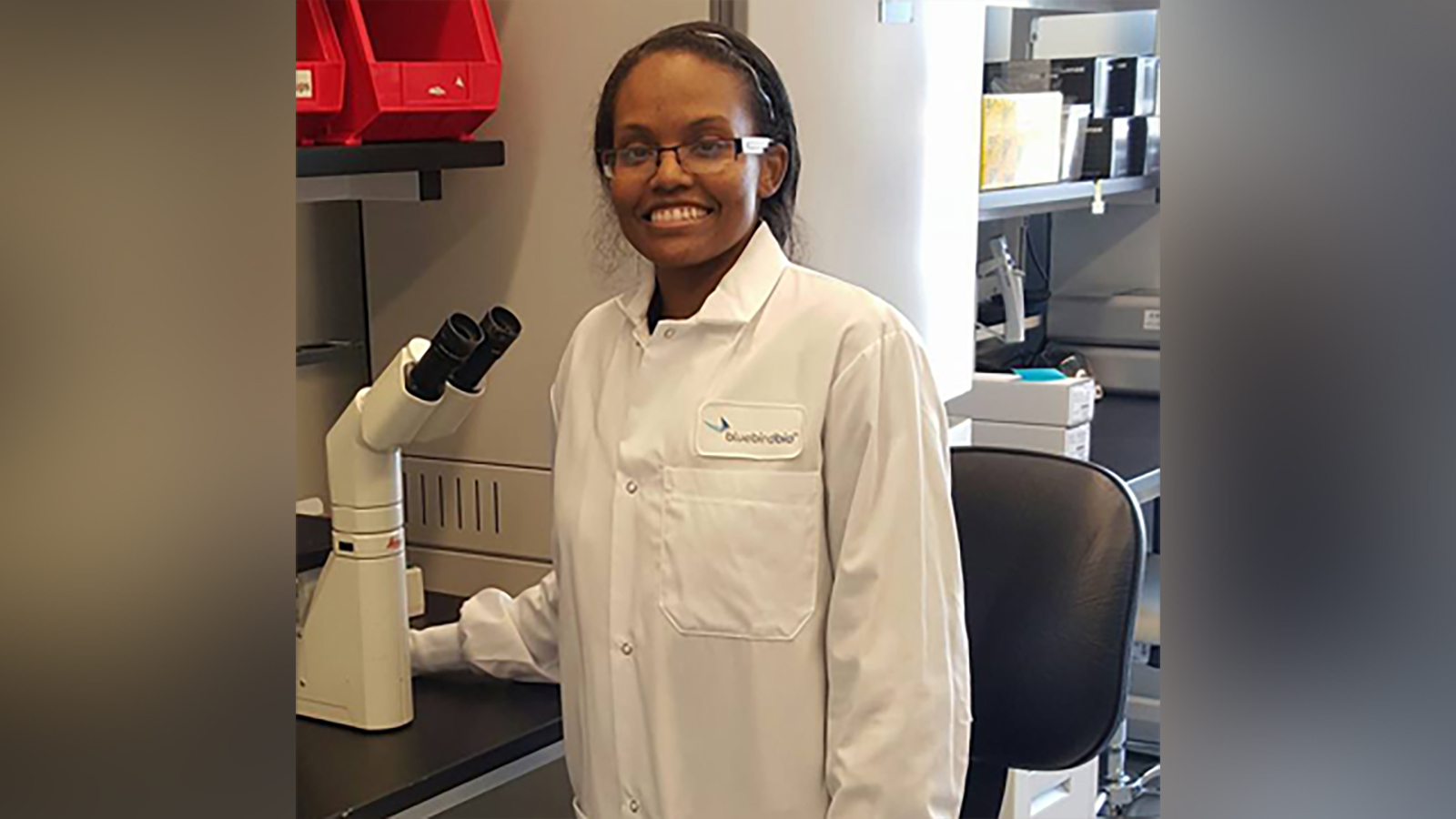

Curious about what causes diseases like hers, she excelled in school and got a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology from Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia. While working on her doctorate she became extremely ill. Her grit helped her push through.

“I wrote papers from hospital beds, presented abstracts from hospital beds, won awards from a hospital bed,” she said.

She eventually earned a doctorate in molecular hematology and regenerative medicine at Augusta University’s Medical College of Georgia.

Bailey won multiple awards while in school, including the Fisher Scientific Award for Overall Excellence in Biomedical Research, and she coauthored several studies published in international scientific journals.

“I think that knowledge, that sickle cell disease was always sort of waiting in the shadows, kept me running forward and pushing ahead.”

Founding the Sickle Cell Consortium

In 2014, Bailey founded the Sickle Cell Consortium, a non-profit that advocates for patients and their families. For her it’s personal — her mother struggled for three years to get young Bailey a proper diagnosis.

The organization helps families find the care they need, including mental health resources, and shares ways to avoid sickle cell crises. It also educates families on the latest treatments and clinical trials.

“I had this rather ambitious goal of creating a mini-United Nations where all of the different sickle cell organizations and patient caregiver leaders could come together on a single level field and identify major needs and gaps.”

The group holds sickle cell “Warrior Conventions,” national community gatherings organized by patients and caregivers. They hold workshops, hear from leaders and scientists and give out more than 100 scholarships, bonding over their shared challenges.

In the US, the blood disease primarily affects people of African or Caribbean descent. Worldwide, it also shows up among people living in Greece, Italy and India.

Today the only known cure is a bone marrow transplant. But the procedure has significant risks and patients need to find a matching donor, which is difficult.

“The registry needs a greater number of Black and brown people willing to save the lives of other Black and brown people,” said Bailey.

Searching for a bone marrow donor

Bailey is fighting her own personal battle to find a donor. She’s had one match but it fell through.

Sickle cell has impacted most of her organs. She’s suffered multiple strokes and has required a complete hip replacement.

There are good days and bad ones when she has a hard time catching her breath or talking. But the fatigue is the biggest problem.

“You can learn to be in pain, but when you spend so much of your life absolutely exhausted and no amount of rest can capture or help you feel better — it throws everything else off.”

Meantime, Bailey fights on, helping find a cure.

She helps drug companies work on gene therapy. She’s on the National Institutes of Health’s Sickle Cell Disease Advisory Committee, and she is an executive member of the government’s Cure Sickle Cell initiative created by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Sickle cell inflicts harm on many fronts. But this tough scientist is pushing back in so many ways– and she’s not alone.

“In the next 5 to 10 years, we are working very hard to make sure that future generations do not have to live with this disease.”