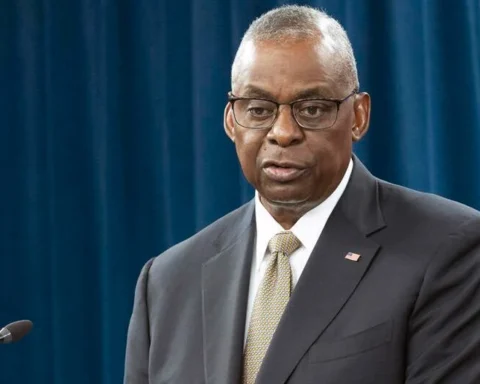

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin on Tuesday announced he will recommend to President Joe Biden a change in the military justice system to take the prosecution of sexual assaults out of the hands of commanders.

“We will work with Congress to amend the Uniform Code of Military Justice, removing the prosecution of sexual assaults and related crimes from the military chain of command,” Austin said in a statement.

A Pentagon review panel submitted recommendations to Austin in the spring, including a recommendation that independent authorities decide whether to prosecute service members in sexual assault cases. If adopted, the change would mark a significant departure from how the military handles sexual assault, which the Pentagon has argued for years should be treated within the chain of command.

Austin’s announcement comes a day before he is set to testify to the House Armed Services Committee in a budget hearing, along with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley.

In early May, Milley threw his support behind the possibility of the change for the first time.

“The issue of sexual assault has plagued our military for quite a while. Sexual assault is a felony, it’s a crime, it’s horrific, but in the military it’s even more than that,” Milley said at the time. “In the military, it attacks the very essence of readiness, combat effectiveness, combat power, because it rips apart at the good order and discipline and the cohesion of a military unit.”

Milley had long opposed removing the investigation of sexual assault from the chain of command, arguing at his confirmation hearing in July 2019 that commanders must retain the ability to hold service members accountable. But the failure of previous measures to have any meaningful impact on sexual assault in the military shifted his position.

“I’m one of the guys who used to argue against that, but we have a problem, a big problem,” Milley said in May. “I haven’t seen the needle move, and people like me have repeatedly, over and over and over again, said, ‘Leadership, leadership, leadership,’ and we’ve tried all kinds of systems over the last years and the needle hasn’t moved.”

A Defense Department survey estimated there were more than 20,000 sexual assaults in the military in 2018, even as the number of sexual assaults reported to the military was a fraction of that.

The support of the defense secretary means that the top civilian and military leaders in the Pentagon do not oppose the change.

The recommendations from the review commission extended beyond sexual assault.

Austin said the panel “recommended the inclusion of other special victims’ crimes inside this independent prosecution system, to include domestic violence.”

“I support this as well, given the strong correlation between these sorts of crimes and the prevalence of sexual assault,” the defense secretary said.

But changes beyond the handling of sexual assault cases may be far more difficult to make. Despite bipartisan support for a Senate bill introduced in late April that would remove the chain of command from the investigation of sexual assault and other crimes, the bill still faces resistance.

Republican Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma, the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said in a statement Tuesday, “I don’t believe this well-intentioned bill will change anything — in fact, I remain concerned that, as written, it would not reduce sexual assault or other crime in the slightest and would complicate the military justice system unnecessarily.”

Pentagon leaders recommended that any changes to the command authority be evidence-based, rigorously examined and focused specifically on sexual assault.

“Diverting nearly all serious offense to judge advocates could be counterproductive to our prevention efforts, which emphasize the critical responsibility of senior leaders,” Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael Gilday wrote to Inhofe. “If the real issue to be addressed is sexual assault, then any change must be focused on that problem.”