If it were the fall, this group of volunteers — folders in hand, walking shoes on their feet — would be knocking on doors to get out the vote in rural Cuthbert, Georgia.

As they walked in the hot spring sun this April and May, these four have another mission. They are using their powers of persuasion to get more neighbors to take the Covid-19 vaccine.

“Excuse me,” Joyce Barlow says to Sherod Shingles, a young man who comes out his front door in shorts and a Utah Jazz shirt, a white medical mask on his face. “Have you had your Covid-19 vaccine?”

The volunteers circle around him at a pandemic-safe distance.

“Nah,” Shingles says. “I haven’t got sick yet either, but you’re right, I need to.”

Covid-19 has hit Randolph County hard. In the early months of the pandemic, it had the highest Covid-19 case rate in the state.

Randolph is also one of the poorest counties in Georgia, and isolated — nearly 140 miles south of Atlanta and more than an hour’s drive from a major highway. It’s the top wheat and sorghum grower in the state, and its county seat, Cuthbert, population about 3,500, is home to the private liberal arts school Andrew College.

Nearly 62% of Randolph County’s population is Black, and it sits in the heart of the historic Black Belt, the string of counties in the Deep South that includes some of the poorest and most rural regions of the country, all with large Black communities.

The county’s racial demographics alone make residents more susceptible to severe disease from the coronavirus. And according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people who live in rural areas face an increased risk of hospitalization and death from Covid-19.

But in Randolph County, the vaccination rate is well below the state average — and Georgia’s rate is among the lowest in the country.

That’s not just a problem for Randolph County and other rural places where vaccines have been slow to take off. Lagging vaccination rates in rural areas could extend the pandemic for the entire country, according to CDC researchers.

The Biden administration’s goal is to give 70% of US adults at least one Covid-19 vaccine dose by July 4, and last week it launched its latest push to draw in the unvaccinated. The federal government is trying to woo people by putting vaccines in community hubs like barber shops; making plans to offer child care; and by organizing rides to vaccination sites. Around the country, incentives are being offered, including beer, guns, scholarships and million dollar prizes.

But the volunteers in Randolph County didn’t want to wait for help or incentives. They’ve been tapping on doors in support of Covid-19 vaccines since March.

‘What are you waiting for?’

This group learned their canvassing skills in the political arena. They’ve volunteered for years with the Randolph County Democratic Committee, which operates a community program, Neighbor 2 Neighbor. Earlier this year, the group wanted to build on momentum from the 2020 election, and launched the program’s nonpartisan vaccine effort.

At first, it focused on seniors who didn’t have the internet access needed to get vaccine appointments with the county health department. Since then, volunteers have expanded their targets and knocked on hundreds of doors.

Just like when they canvass to get out the vote, the volunteers are prepared with answers to questions.

Some who come to the door say they’ve heard the Covid-19 vaccines cause infertility. Barlow, a canvasser and nurse, fields that one — she explains that it doesn’t affect fertility, and she can share the research to make it clear.

“Some tell us it’s of the devil,” Barlow says. With religious objections, canvassers talk about how God inspired scientists to make the vaccines. Sometimes the volunteers attend the same church as the person they’re canvassing, and can name fellow church members who’ve already been vaccinated.

If people say they don’t trust government, or vaccines were developed too quickly, “we listen to people’s concerns and then try to help educate them and give them food for thought,” Barlow said. “If they still say that they want to wait and see, I listen, but it’s kind of baffling, because I always ask, ‘What are you waiting for? To see how well things are going to go? We already know that. They go well when people are protected.’ ”

Not all residents in rural Randolph County are hesitant to get vaccinated.

While many vaccine appointments are available online, about a third of residents in Randolph County don’t have home internet, according to Census figures.

The median household income here is half the amount of Georgia’s, with a third of the county below the poverty line. Some may not realize Covid-19 vaccines are free and insurance isn’t required, and it can be hard to get time off from work or secure child care.

Randolph County has the highest percentage of households in the state without access to a vehicle — almost 20% — according to Census estimates analyzed by the CDC. That can make it hard to get to an appointment.

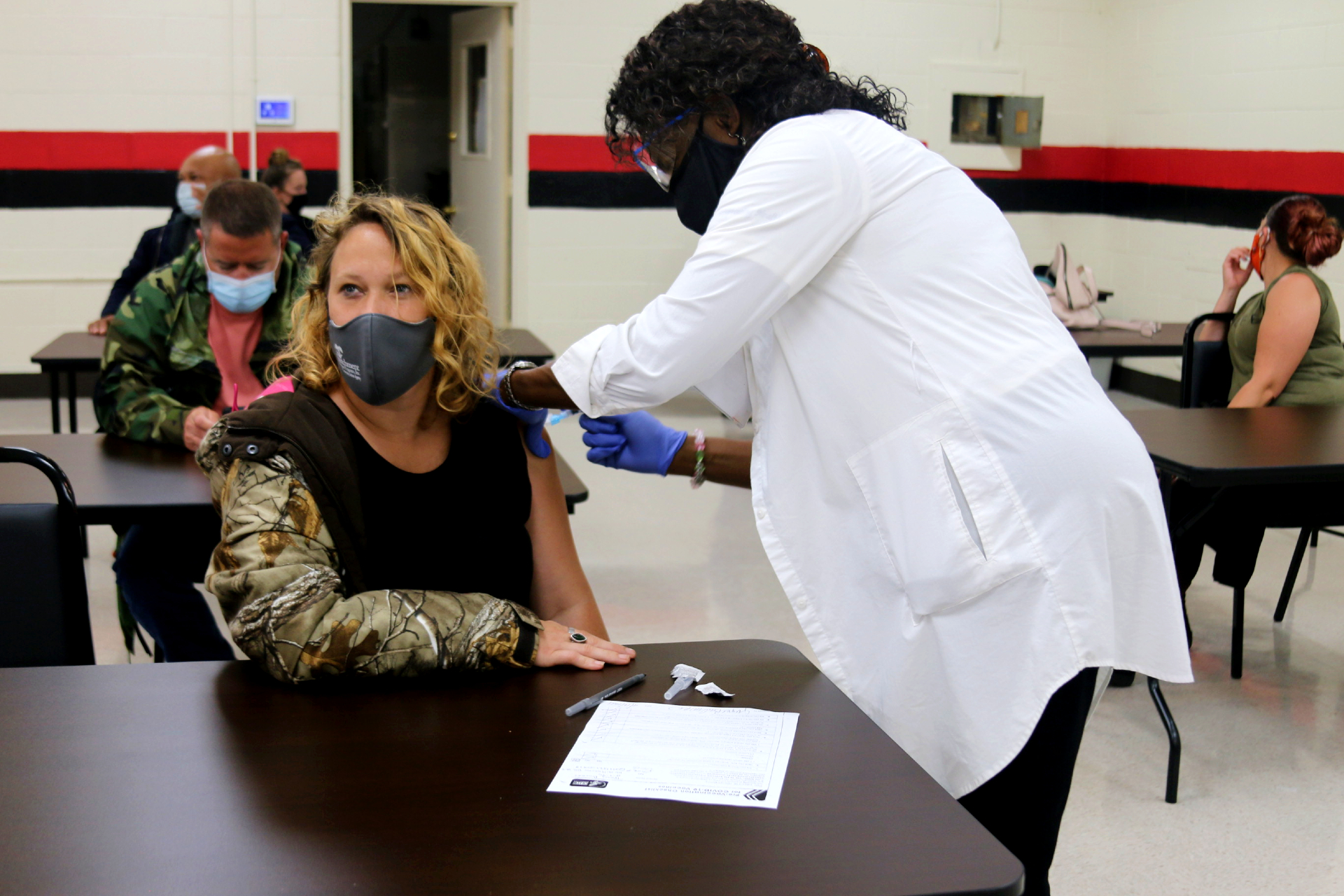

To take on issues of access, the Neighbor 2 Neighbor volunteers organized their own Covid-19 vaccine clinic for April and May with the help of a local doctor.

When deciding where to put the clinic, they chose a central, walkable location and provided transportation, if needed. They signed people up for the clinic as they knocked on doors — no internet required.

“We do this for each other because otherwise, the county just doesn’t have the manpower to vaccinate residents quickly here,” said Bobby Jenkins Jr., a vaccine canvasser and chair of the local Democratic Committee. “We don’t want to let anything stand in the way of getting people protected.”

Canvasser Sandra Willis poses a question to Shingles, the man who answered the door one day this spring: “Sherod, why haven’t you gotten your vaccine yet?”

Shingles says he simply hasn’t gotten around to getting vaccinated. Still standing in his front yard, the group makes a plan.

“We’ll be calling you on Saturday to make sure you can come to our clinic that day,” Willis tells Shingles, knowing from experience that effective persuasion often requires follow-up.

“Sherod, you’re going to be the first one I give the vaccine to,” Barlow, the nurse, teased, saying, “Looking at your shoulders, it will be real easy.”

Making a way out of no way

It seems everyone in Randolph County has a story of someone who died or was seriously ill from Covid-19.

One of the canvassers, Willis, says her brother caught Covid-19 at a nursing home that lost many residents. He pulled through, but Willis also lost one of her best friends and a pastor she knew. They were two among hundreds of cases in the region connected to a couple large funerals that became superspreader events in February 2020. With area hospitals overwhelmed at the time, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp sent the National Guard to help.

The volunteers have a sense of urgency around vaccination against Covid-19: If people in Randolph County do get seriously ill, finding care is difficult.

In October, the county’s only hospital closed. It had struggled financially for years, but the pandemic put “the nail in the coffin,” hospital CEO Kim Gilman said.

The county has only one ambulance to cover 431 square miles. The nearest hospital now is a 45-minute drive, and to get to the nearest ER, these Georgia residents have to go to Alabama.

At the closing ceremony for the hospital in October, a minister said they have to push forward and “make a way out of no way.”

So for these volunteers, their way is organizing their own vaccine clinic and spreading the word door to door.

Out canvassing the unvaccinated one day this spring, the group leaves a flier at a house with a handwritten sign that says, “Because of the coronavirus NO visitors until further notice. THANKS!!!”

But from next door, Tiffany Barnes pokes her head out to see what’s going on.

“How y’all doing?” Barnes asks, a shaking chihuahua named Cisco tucked under her arm.

Barlow waves a flier at Barnes. “We are canvassing to make sure people know about our vaccine clinic. Do you have yours?” Barlow asks.

Barnes has not. She signs up immediately, promising to bring her mother, too.

“We will happily take care of you both,” Barlow tells her. “You can bring Cisco too. We can’t vaccinate him, but he’d be great company.”

As they take down her information. Barnes thanks them for their efforts.

“It’s a real blessing that you are actually going around door-to-door, getting people to sign up,” Barnes says.

“That’s what this is all about. Neighbor to neighbor. As soon as we get herd, or community immunity for all our neighbors, then it will be safe for all of us to go out. I know everybody’s been cooped up,” Barlow tells her. “We want to get everyone protected. We are, after all, our brother’s and sister’s keepers.”

At the clinic that Saturday, the volunteers were able to vaccinate 80 people with the Moderna Covid-19 vaccine — including those they met going door to door.