A Black women’s advocacy group filed a lawsuit Tuesday accusing Johnson & Johnson of selectively marketing the company’s talcum-based products, including Johnson’s Baby Powder, to African-American women despite knowing for years that the items had been linked to ovarian cancer, an allegation J&J denies.

The pharma giant sold talc-based powder for more than a century, according to its website, before issuing a recall of 33,000 bottles in 2019 and discontinuing its sale in the United States and Canada in May 2020. But even then J&J said it would allow existing inventory to be sold until it runs out.

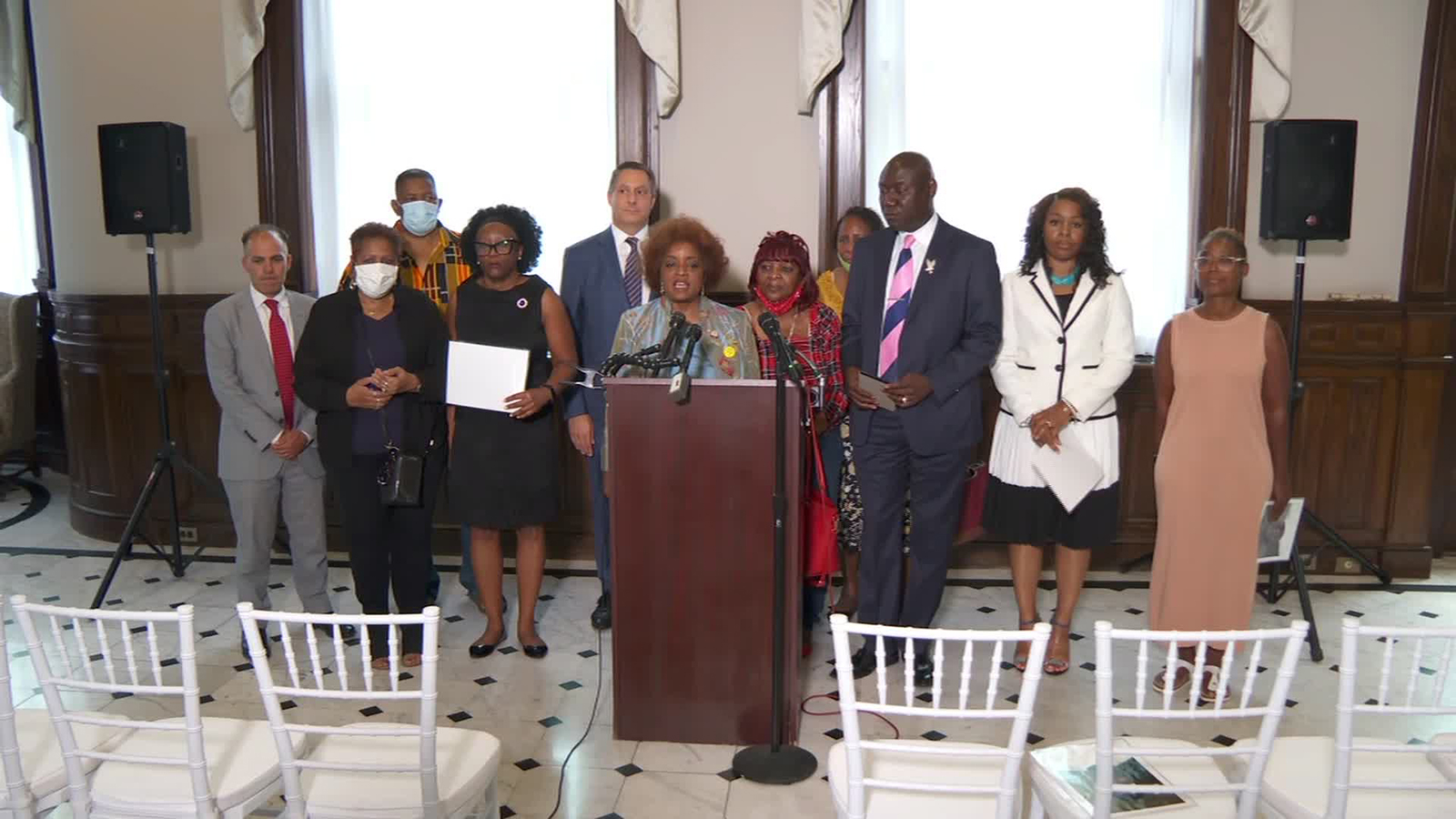

Attorneys for the National Council of Negro Women, including prominent civil rights lawyer Benjamin Crump, filed their complaint in the Superior Court of New Jersey Tuesday morning before hosting a press conference at the council’s office in Washington D.C. a short time later.

Janice Mathis, the group’s executive director, said the goal of the council’s lawsuit is to create awareness about the health risk she says J&J’s talc-based powder products may pose to those who have used them and to encourage Black women in particular to get cancer screenings. African-American families have commonly used Johnson & Johnson powder products for decades to prevent excess perspiration.

“We’re going to mount a campaign to make sure every Black woman and her family understands that you may have a lurking illness that you may have to get treatment and care for,” Mathis told reporters on Tuesday. “[J&J] knew early on that it was almost impossible to mine talc without contaminating it with asbestos. We know they knew it because they’ve taken it off the market. You can’t buy it now.”

Johnson & Johnson said Tuesday that its 2020 decision to discontinue the sale of its talc-based baby powder in the US and Canada “had nothing to do with the safety of the product.”

“Demand for talc-based Johnson’s Baby Powder in North America has been declining due in large part to changes in consumer habits” fueled by “misinformation around the safety of the product and a constant barrage of litigation advertising,” the company told CNN Business via email.

J&J said the allegations made in the council’s lawsuit are false, pointing out that its talc-based powder products are still sold in many countries and a non-talc-based version of Johnson’s Baby Powder is still available for purchase in the United States.

“The idea that our company would purposefully and systematically target a community with bad intentions is unreasonable and absurd,” the company said. “Johnson’s Baby Powder is safe, and our campaigns are multicultural and inclusive. We firmly stand behind the safety of our product and the ways in which we communicate with our customers.”

The National Council of Negro Women’s lawsuit filing came less than two months after the US Supreme Court declined to review a Missouri appeals court ruling that upheld a $2 billion award to a group of women who sued J&J after developing ovarian cancer, which a jury determined stemmed from exposure to asbestos in the company’s talcum-based powders.

An estimated 12,000 women and their families have sued J&J over the past 25 years, according to The New York Times, after multiple studies found a notable association between talc use and ovarian cancer. But scientists still aren’t certain that asbestos-free talc causes the deadly disease.

The American Cancer Society says talc that has asbestos in it “is generally accepted as being able to cause cancer if it is inhaled,” but notes that “the evidence about asbestos-free talc is less clear.”

The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer says talc that contains asbestos is “carcinogenic to humans” and classifies use of talc-based body powder on genital areas as “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” according to the ACS. Most experts agree more research is needed.

Crump argues that Johnson & Johnson internal documents cited in the council’s complaint show executives at the company “doubled their efforts” to market J&J powder products to Black women, a campaign he says was sparked by a dip in sales following news stories about talc-based powder’s potential links to ovarian cancer in the 1990s.

“This multibillion dollar company should dedicate as many resources giving warning to these women as they did trying to target these women,” Crump said.

The council’s complaint cited a 2004 J&J memo suggesting the company “team up with Ebony magazine” to market its Shower to Shower talc-based powder products at African-American concerts and jazz festivals as well as at Black churches, beauty salons and barber shops.

“African American consumers in particular would be good to target with more of an emotional feeling and talk about reunions among friends, etc.,” the J&J memo stated, according to the complaint.

The lawsuit also cited a 2006 J&J internal presentation that pushed for a “new business model” for powder products amid stagnating sales. The complaint said the new business model involved “strategically and efficiently target[ing] high propensity consumers.”

“Those included Black women, 60% of whom were using baby powder by this time, as compared with 30% for the overall population,” the complaint said.

The “Key Issues/Learnings” portion of a 2008 J&J presentation also noted that “African Americans have high affinity for the category and tend to be heavy users,” according to the council’s lawsuit.

“This presentation demonstrates J&J’s clear intentional marketing to Black women, and its knowledge that Black women are and have been particularly ‘heavy users’ of its talc-based powder products,” the complaint stated.

J&J told CNN that the lawsuit’s marketing and business practice allegations are “misleading.”

“Efforts to determine who our customers are, and the use of advertisements that are meaningful to them and speak to their life experiences, is the very definition of marketing,” the company said. “We believe that marketing to every community is a sign of respect and are proud that we have been pioneers in multicultural marketing.”

Crump and Mathis were joined at the press conference by family members of Black women who say their loved ones died of ovarian cancer after spending years using J&J talc-based powder products. Constance Seltzer said her grandmother Goldie Hoes died in May of 2018 after using Johnson’s Baby Powder for decades.

“She taught us to use talcum powder. Everybody in our family used it,” Seltzer told reporters. “She was the matriarch of this family. She was my glue. There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t miss my grandmother.”

Two-time ovarian cancer survivor Wanda Tidline told reporters on Tuesday that she was originally diagnosed in 2012 despite having no history of ovarian cancer in her family.

“I have to deduce that it developed because of the many years I used J&J,” she said. “I felt confident in the product because of where it was advertised on television.”

The group of women concluded their press conference by chanting “Black women’s lives matter!”

J&J’s leaders are exploring a plan to offload its talc-powder lawsuit liabilities into a new business that would file for bankruptcy to avoid payouts, according to seven anonymous sources familiar with the matter who were cited in a Reuters exclusive earlier this month.

On July 18, attorneys representing thousands of additional ovarian cancer survivors who are suing J&J in a separate federal lawsuit previously filed in New Jersey called on Congress and the SEC to take action barring the alleged move.

The company told CNN Business Tuesday that it hasn’t chosen any particular course of action, other than to “defend the safety of talc” and “litigate these cases in the tort system, as the pending trials demonstrate.”

Crump said on Tuesday that J&J should take financial responsibility for the alleged harm it has caused.

“It wasn’t enough for them to victimize our Black women while they were living or battling cancer,” Crump told reporters at the press conference. “Now they are trying to limit the liability of trying to make Black women whole.”