Shanta Matthews and her family were three months behind on rent last week and were preparing to be booted from their two-bedroom condo in Charleston, South Carolina, when they got a last-minute reprieve from the federal government.

US health officials issued a new eviction moratorium on August 3, temporarily barring landlords from removing tenants in regions with substantial or high Covid-19 transmission rates, (which applies to most of the country). For a moment, Matthews, a 41-year-old mother of two, breathed a sigh of relief.

The ban on evictions bought her and her fiancé, Karel Williams, more time — the moratorium expires on October 3 — but it didn’t resolve the $5,300 in back rent she still owed her landlord, Tom Taft, Sr., owner of Taft Family Ventures, a real estate development firm based in Greenville, North Carolina.

“It was kind of a breath of fresh air, but I’m not sure if it’s going to save us,” Matthews told CNN Business of the moratorium.

Limits of the eviction moratorium

The existing stay on evictions may prevent law enforcement from removing renters from homes, but it doesn’t stop landlords from filing eviction requests, according to attorney Mark Fessler, head of the housing unit at South Carolina Legal Services, a non-profit law firm specializing in civil law cases for low-income communities.

“That’s how the courts have interpreted the moratorium and how the CDC has explained the past moratorium in briefing in federal court,” Fessler told CNN Business on Monday.

Even if renters can’t be removed, eviction court filings can stain a person’s financial history for years.

“It can, certainly for low income individuals, [make] it harder to find other housing and either [make] that housing more expensive or [force] them into substandard housing,” Fessler added.

Matthews recently applied to receive rent relief funds through a county Emergency Rental Assistance program funded through the $46 billionCongress set aside between the December stimulus plan and the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan.

As of Monday afternoon, however, her landlord had refused to fill out a document agreeing to receive funds from the program, insisting that she pay a total of $3,600 in back rent in exchange for his cooperation.

“He’s holding up the process for me to help get him his money,” Matthews said of Taft on Monday.

Taft had his property manager withdraw his local housing court request to evict Matthews’ family on Friday when he says Matthews paid him $1,600 in back rent. He said Matthews had agreed to pay an additional $2,000 on Monday before he signs her rental assistance papers.

In the past, Taft said it has taken six to eight weeks for him to receive federal rent aid funds for Matthews and he’s concerned she won’t have enough to pay future rent if she falls behind again.

“She’s going to be in this same situation and I’m going to have a lot less patience later,” he said. “We work with tenants. If they honor what they say they’re going to do, then we work with them.”

On Tuesday, Taft agreed to fill out Matthews’ paperwork even though he said Matthews didn’t give him the additional $2,000 she agreed to pay in exchange for his cooperation.

I’m OK with that,” he said. “We’re going to proceed … We’ll get that done today.”

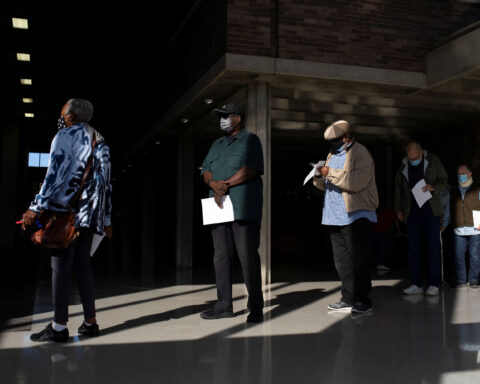

Evictions hit communities of color

Researchers and South Carolina housing assistance officials say this type of rental dispute has become more commonplace in the pandemic era.

Matthews and her fiancé are two of the millions of Americans who were laid off during the spring of 2020, when state and local governments across the US forced many non-essential businesses to shut down to stem the spread of Covid-19.

The original eviction moratorium initiated in September of last year was extended multiple times before expiring on July 31.

Today nearly 6.4 million US households now owe their landlords more than $21.3 billion in back rent, according to an estimate by the National Equity Atlas created by PolicyLink, a research institute based in Oakland, California.

An estimated 19% of American households with children say they are behind on rent, and roughly 15 million Americans overall are in danger of being evicted, according to a recent study from the Aspen Institute, a policy studies nonprofit headquartered in Washington, DC.

Americans of color, like Matthews and her family, will be disproportionately hurt by upcoming evictions, the institute’s researchers found. About 22% of Black renters and 17% of both Latino and Asian renters say they are in debt to their landlords, compared with 15% overall, according to the report.

South Carolina leads the nation, with 29% of adults saying they’re behind on rent.

The eviction moratoriums have left landlords and property managers with the responsibility of providing housing to millions of US renters without sufficient resources, according to Bob Pinnegar, president and CEO of the National Apartment Association, an industry group representing property owners.

Taft said the moratoriums and the federal rental assistance program have left landlords like him in limbo.

“I was OK with it as long as it works,” he said of the moratorium. “A lot of states are slow-walking these payments and less than 15-20% of the money appropriated has been spent. That’s what’s been going on in South Carolina. We don’t have much confidence in how much money we’ll get and whether we’ll be made whole. … It becomes a question of business and you can’t do this forever.”

Low pay, high rent

The catalyst for South Carolina’s eviction crisis is a combination of too many low-wage service and hospitality jobs and relatively high rent rates, according to Brian Grady, chief research officer at the South Carolina State Housing Finance and Development Authority, known as SC Housing.

Grady’s agency administers home ownership and affordable rental housing programs for low- and moderate-income South Carolinians. It’s also in charge of distributing a portion of the $46 billion Congress has set aside for rent aid assistance.

Rent in South Carolina cities like Charleston, Columbia and Myrtle Beach may not be high when compared with markets like New York or San Francisco, but Grady says South Carolina is disproportionately populated with low-income residents.

“A quarter of renter households are severely cost burdened, meaning they spend more than half their income on rent and utilities,” Grady told CNN Business. “There’s a lot of low-wage service jobs in South Carolina and those are the kind of jobs that were most hard hit by the initial impact of the pandemic.”

The information gap

Matthews, who worked as a medical assistant at a doctor’s office before being laid off, says not enough is being done to let people know about rental assistance programs. She only found out about the aid after searching for solutions online.

“They’re not promoting it enough,” Matthews said. “You see [news] stories about PPP more than you see emergency rental assistance. They talk about stimulus…but they don’t advertise or promote the fact there’s money out here to get help. These things should be plastered for people to know there’s help out there for you. You just have to apply.”

Matthews’ fiancé, who also was laid off in March 2020, found work as a line cook at a local barbecue restaurant in May of this year. But her own job search hasn’t been as fruitful, she says, despite applying for many positions. The couple used their previous rent assistance aid money and some of their stimulus check savings to pay $11,000 in back rent in March of this year, after they received their first of two eviction notices from Taft.

She says she stopped receiving unemployment benefits the same month. South Carolina Gov. Harry McMaster officially ended the state’s participation in federal pandemic-related unemployment benefits programs on June 30 to compel South Carolinians to return to work.

“Our governor is cutting off unemployment, but he’s not telling his people about the other programs that can help them with utilities, rent and things that can help them stay in their homes,” Matthews said.

SC Housing says it promotes the emergency rental assistance program through churches, food banks, community centers, local government offices, landlord and realtor associations and a network of community non-profits to educate people about available funds.

“We have also advertised through direct mail, texts, TV and radio, in addition to distributing materials at special community events,” SC Housing communications and outreach director Renaye Long said.

Lawmakers in states like South Carolina need to pass suppression laws that would hide or erase eviction records for renters who were impacted by the pandemic, says Covid-19 Eviction Defense Project’s executive director Zach Neumann, who co-authored the Aspen Institute study.

“That would mean they don’t have to drag that anchor around for the next seven years,” Neumann told CNN Business. ” More broadly I think you can talk about changing the way you do credit reporting in America.”