Visitors to New York’s Christopher Park this week were greeted by the bust of Marsha P. Johnson, stoic yet softly smiling. She’s wearing a tiara on her head, designed to loop live flowers through. It evokes a famous photograph of Johnson, beaming with a crown of brilliant blooms strewn through her hair.

The bust was erected on what would have been Jonhson’s 76th birthday — and more than two years after city officials announced they were going to create a monument to Johnson and fellow transgender activist Sylvia Rivera.

But this statue of Johnson, a Black transgender woman who devoted much of her life to the movement for LGBTQ rights, wasn’t created with the city’s involvement or approval. A group of enterprising artists and activists just got tired of waiting for the monument and made it themselves.

Writer and activist Eli Erlick, sculptor Jesse Pallotta and fellow organizers created a bronze bust of Marsha “Pay it No Mind” Johnson and installed it themselves in the small park, a part of the Stonewall National Monument. Their work of art is a stunning portrayal of Johnson, but it’s also a political act — one that honors Johnson’s spirit of serving LGBTQ people without the support of those in power.

“We cannot stay idle and wait for the city to build statues for us,” Erlick said in a statement. “We must create representation by and for our own communities.”

The bust was made without the city’s involvement

Johnson and Rivera were set to receive memorials near the Stonewall Inn, the city announced in 2019, but progress has since stalled. Erlick, who coordinated the sculpture’s creation and installation, said the group “decided to create the artwork ourselves” because NYC Parks, the city’s department of parks and recreation, often takes years to approve a single statue.

“Statues of women, people of color, and trans people are often denied behind closed doors,” Erlick said in an email to CNN. “The trans community took matters into our own hands.”

The NYC Parks Department told CNN it doesn’t have the final say in how long the bust will stay up, given the area’s inclusion in a national monument. The National Parks Service did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Pallotta created the bust using the work of Tourmaline, an activist and filmmaker who archived hundreds of photos of Johnson, which helped Pallotta get a feel for Johnson’s features from every angle, Pallotta told CNN.

The portrait, Pallotta said, is “almost an idealized depiction” of her features, designed to portray her “as an elevated being.”

The bust of Johnson is just one of a few statues of women in the city’s parks, Erlick said, and the first to honor a transgender woman.

Johnson advocated for LGBTQ rights for most of her life

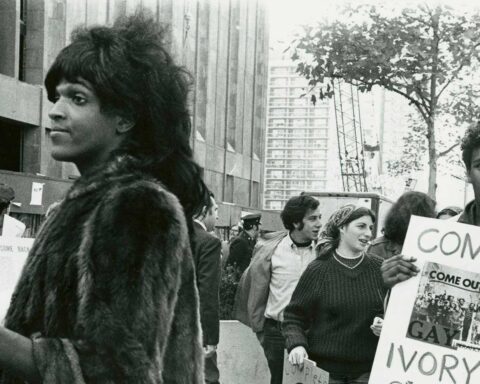

Though Johnson’s activism was concentrated in New York, she demonstrated for the rights of gay and trans Americans throughout the country. She played a key role in the 1969 uprising at the Stonewall Inn, located just across from Christopher Park, in which police raided the bar and violently clashed with gay and transgender patrons.

“We were just saying, ‘no more police brutality’ and ‘we had enough of police harassment in the Village and other places,'” Johnson said in a 1989 interview.

She and Rivera co-created the group STAR, which at the time stood for Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, to house LGBTQ youth. Johnson was homeless for periods throughout her life, too, often participating in survival sex work, according to the Office of LGBTQ+ Affairs for Union County, New Jersey, where Johnson was born.

She was also a staunch activist for AIDS survivors, organizing with ACT UP New York until her death in 1992, when her body was found in the Hudson River.

Johnson’s influence lives on today through organizations like the Marsha P. Johnson Institute, created by transgender advocate Elle Moxley, that serves Black transgender people.

The bust is the latest in a long line of queer art with a statement

The act of creating the bust and installing it without first receiving official permission “takes place within a very vaunted tradition of queer artmaking,” said Jonathan Katz, an associate professor of practice in art history at the University of Pennsylvania.

Pallota and Erlick follow in the steps of artists like David Wojnarowicz, who created murals at an abandoned Hudson River pier, and Keith Haring, who sketched in chalk at subway stations, said Katz, a foremost expert in queer art history.

“The guerrilla movement has long been a part of the DNA of the queer art movement,” he said.

But the bust of Johnson is indicative of a “newly assertive kind of political movement,” Katz said, one that takes matters into its own hands when the city has good intentions but doesn’t act. And the manner in which it was erected is a fitting homage to Johnson, too, he said: She was “all about visibility, about finding community, about pulling people together in ways that were not always, sort of, authorized,” he said.

The bust’s placement “is also a comment on the existing Gay Liberation Monument,” the organizers said in a statement, referencing four statues of two same-sex couples, cast in bronze and painted in stark white, that were installed in the park.

George Segal was commissioned to create the monument in 1979. Segal, who had previously created memorials for the Holocaust and the Kent State Massacre, initially believed a gay artist should create the artwork but decided that “living in the art world” had made him sympathetic to the gay friends in his life, per NYU. As was Segal’s style, the statues were drenched in white paint.

Critics of the piece say it “whitewashes” the Stonewall Riots and queer liberation movement. Transgender women of color like Johnson, Rivera, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy and many more were instrumental in organizing for LGBTQ rights and serving LGBTQ people when mainstream organizations would not but aren’t represented by the existing monument.

“This bust in that place rearticulates a message of inclusion,” Katz said.

The bust is ‘designed to be temporary’

A plaque on Johnson’s bust remembers her as a lover of poetry, flowers, space and the color purple. It includes, too, a quote from Johnson on the nature of activism and community change.

“History isn’t something you look back at and say it was inevitable,” the plaque reads. “It happens because people make decisions that are sometimes very impulsive and of the moment, but those moments are cumulative realities.”

Erlick and Pallotta told CNN on Friday that they expect the monument to Johnson remain a bit longer, but Pallotta said the work was “only designed to be temporary.” They want to see the city follow through with their initial plans to memorialize Johnson and Rivera, they said.

“My end goal is that the city reinitiates the project to give monuments to Marsha and Sylvia, and that the current Black trans women leaders of NYC are involved in the process, including artist selection and design of a monument,” Pallotta said.

For now, though, the floral bust of Johnson will remain in Christopher Park, looking every bit the regal figure her loved ones considered her to be.

“Anyone who knew Marsha, and I did briefly like so many other people, knew that inclusion, invitation, maternal warmth — these were her defining qualities,” Katz said. “The bust instantiates that.”