On a warm September afternoon, Mona Scott sat on the front porch while her home baked like an oven. As she ran a frozen water bottle across her forehead and arms, Scott told CNN her air conditioning broke 10 days earlier and had not yet been fixed.

“The windows are painted shut,” Scott said. “We come outside at night to sleep because it’s too hot inside.”

Like Scott, residents in the low-income communities across south and southwest Atlanta are struggling to cope with the hottest summer since the Dust Bowl period of the 1930s.

“It’s just so hot,” Scott said as she wiped sweat from her brow.

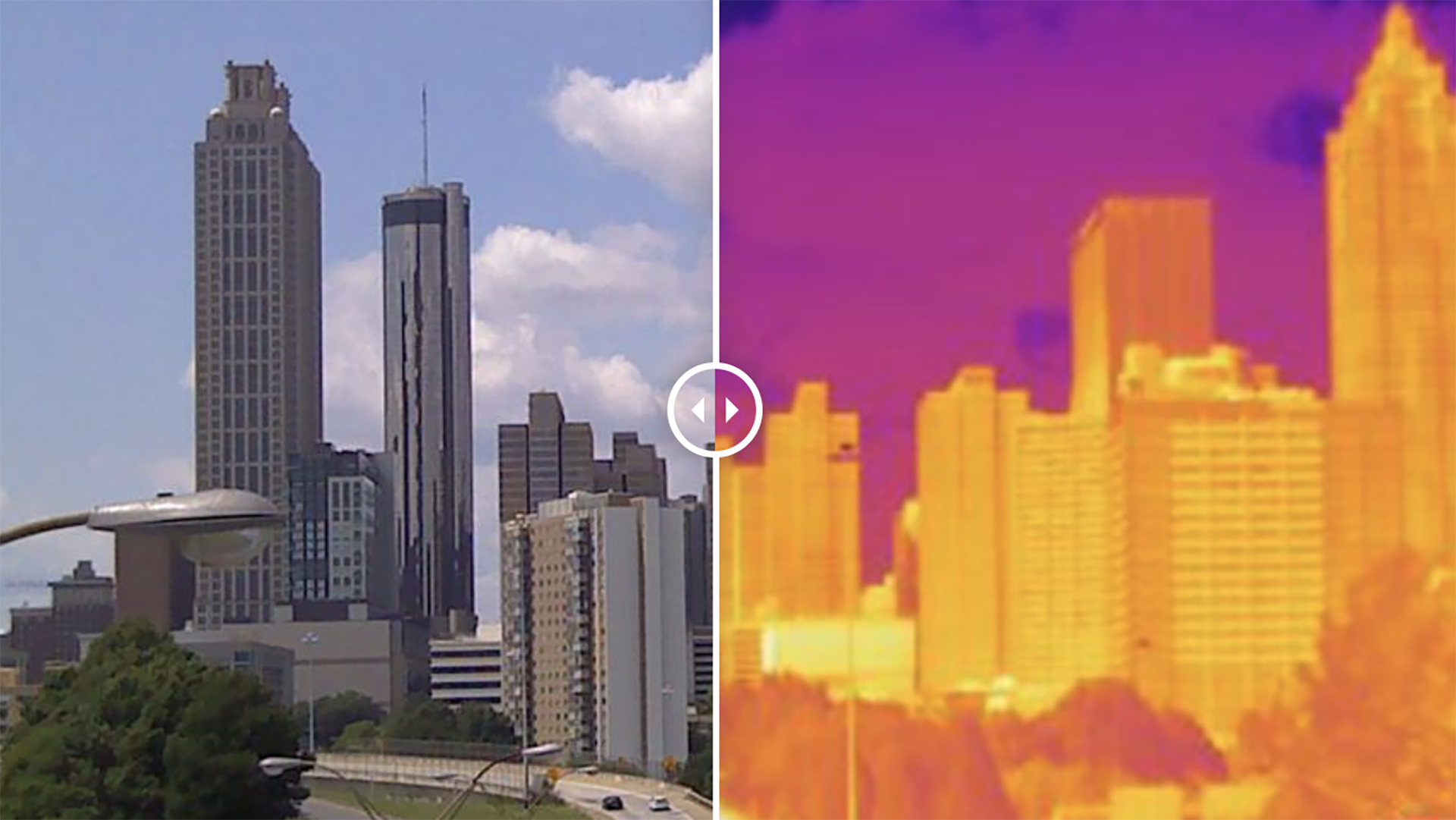

Heat waves are the most lethal weather-related disaster in America. And these health risks are not distributed equally. During extreme heat events, a few city blocks can mean the difference between a manageable 80-degree afternoon or a sweltering, 100-degree sweat fest.

The staggering temperature difference is due in large part to historical redlining, a federal government-sanctioned effort that began in the 1930s that amplified segregation by denying loans and insurance to potential home buyers in poorer neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color.

While the racist practice was banned in the late 1960s, its effect is still apparent.

Across America’s largest cities, Black homeowners are nearly five times more likely than White families to own homes in these historically redlined communities, according to a study by Redfin. These communities, like where Scott resides in South Atlanta, endure the greatest burdens of our rapidly warming planet, and now tend to be the hottest and poorest areas.

Extreme heat threatens the health and well-being of underserved communities today, while predominantly White neighborhoods reap the cooler benefits of decades of investment.

“I went to get groceries the other day and I thought I was going to pass out.” Scott told CNN. She said she suffers from high blood pressure and diabetes, which are underlying health conditions made worse by excessive heat.

Keeping the lights on is hard enough financially for Scott, and so many other disadvantaged community members, let alone having access to reliable air conditioning.

Confronting environmental racism

Some cities, like New Orleans and New York, suffer from the worst urban heat in the nation, according to a recent study by Climate Central. Atlanta, affectionately known as “Hotlanta,” is also particularly hot.

Spelman College, a historically Black college in Atlanta, partnered with a NOAA campaign and other universities to map the hottest and most vulnerable communities. Spelman’s involvement is significant because it is the first time a historically Black college or university has led an initiative such as this, Na’Taki Osborne Jelks, assistant professor of environmental and health sciences at Spelman College told CNN.

“As we think about global challenges like climate change, this is one of the issues that disproportionately impacts Black and other communities of color,” Jelks said. “So, it’s very important that we are at the table.”

Black people are 40% more likely to live in areas with the largest projected increase in heat-related deaths if the planet reaches 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, according to a recent EPA report. This rises to 59% if the planet reaches 4 degrees Celsius.

In August, global scientists said warming had already reached approximately 1.2 degrees Celsius and showed no signs of slowing.

People like Scott are the reason that NOAA’s National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) campaign has been mapping America’s urban heat islands since 2017. This community-led, multi-city program has helped city planners identify and map the hottest neighborhoods of American cities.

The urban heat island effect occurs when a city’s unshaded pavement and buildings absorb heat from the sun during the day and radiate that heat into the surrounding air. This can make even average summer days feel unbearable in dense urban environments, especially to those without access to reliable cooling like Scott.

Jelks and Guanyu Huang, an assistant professor of environmental and health sciences at Spelman College and the local leader of Atlanta’s heat mapping campaign, are both very passionate about this work. They are hopeful that the data will result in changes in the city in which they both reside.

“So, this data will actually help people in Atlanta, especially in the downtown area or intercity area, the people who are actually suffering from heat and also don’t have access to an AC system,” Huang said.

Other cities that have been part of the NOAA heat-mapping campaign have taken the results and made changes, such as planting more trees or adding more parks to areas that are suffering from the worst heat.

The inequities in green space is striking as you traverse Atlanta. Driving through Scott’s neighborhood there are fewer and smaller parks than nearby neighborhoods that are predominantly White, and natural shade from trees is also lacking.

Despite being called “a city in the forest,” where trees are abundant across much of the Atlanta metro, heat inequality remains.

This study is personal

Brionna Findley, a former Atlanta resident and a volunteer for the urban heat island campaign, has experience with the inequity. She has witnessed firsthand her community’s lack of access to air conditioning and shaded green space.

Findley says she and her family endured countless heat waves in Atlanta when they were there. And it seems to only be getting hotter.

“When I was taking a temperature reading for that specific day, we had higher temperatures when it came to low-tree-cover areas, with more infrastructure and more asphalt on the road,” Findley said. “It was extremely hot, you can feel it. It wasn’t something that was hidden. Like, you felt the temperatures.”

This campaign is personal for Findley after her own grandmother experienced signs of heatstroke.

“It was like one of the hottest days in Georgia. And we went out and we were out walking around the shopping mall center, and we had to go home because you could see, like one side of her face was going down,” Findley explained. “She was having slurred speech. That was very, it was very hard to see that. I was very scared.”

The human body is highly sensitive to heat. Extreme heat on its own can cause heat exhaustion and heatstroke, but it can also worsen underlying conditions like heart and lung problems, obesity and diabetes, among other health issues. These preexisting conditions decrease the body’s ability to adapt to environmental changes like high temperatures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“She’s OK. But we definitely don’t let her go outside that much, especially when it’s hot out there,” Findley said. “Like, Grandma, you need to stay inside today and do some inside activities.”

It could get worse

In general, temperatures across much of the contiguous United States are warming and city environments are experiencing the brunt of the heat due to these urban heat islands. The warming trend is apparent in a new NOAA analysis of average weather.

In Atlanta, the city now averages 11 more 90-degree, or hotter, days in the summer, compared to the old 30-year average. Salt Lake City averages 10 more days at 90 degrees or above, and Houston gained nine days.

See how the climate crisis has changed weather in your city

Once the urban heat islands are mapped, city planners will have more tools to combat environmental inequalities, which experts say will only be exacerbated by the climate crisis.

“If we combine all the data from all the cities together, it will be helpful for all levels of government from state level, federal level to create some climate resilience plan for the entire country. So, that’s what we can do through here,” Huang said. “We can use it to do research, to teach your climate change classes, to tell the people that climate change is actually right there, it’s just next to our neighborhood.”

Potential solutions for a better future

City planners from Houston used the data from the campaign’s 2020 analysis to enact a Climate Action Plan designed to help build resilience against climate disasters, including extreme heat.

Richmond, Virginia, is utilizing the information to transform city-owned land into public green space, providing cooling options to those in need.

“I used to live in New York, and they had cooling centers where people that was homeless could come in in the daytime to keep from being out in the heat, drink water, maybe get a sandwich and a snack. And I ain’t never seen that down here (in Atlanta),” Scott said. “I think they (city planners) should plant trees in hot areas, especially around bus stops. I think they need to open up some kind of center, you know, to help keep people cool.”

While Atlanta has had cooling centers available during extreme heat waves, in the past these centers were not open overnight, when high temperatures can have a particularly severe health impact. The City of Atlanta did not respond to a request for comment about cooling center availability.

Covid-19 has also made unofficial cooling centers, like libraries or malls, harder to access, while they may have been more available to the general public before the pandemic. In some cases, Scott has found these locations are simply closed.

Jelks said that these communities need investments and solutions in a way that doesn’t end up displacing them.

“We can add new trees, but we’ve got to make sure that there are also policy supports to keep the people who are currently suffering from the lack of access to these amenities,” Jelks said. “We want to keep them in place and make sure that they are not displaced by gentrification and moved out of their communities.”