Joel Alvarado was 6 years old when his mother pulled him aside and asked him to be discreet as he was getting ready to meet his grandmother in Puerto Rico.

“She made me aware that my grandmother was much darker than my other relatives, especially from her side of the family, and she didn’t want me to say anything out of turn or something about her skin color,” said Alvarado, 50, the executive vice president of the Atlanta-based government relations firm Ohio River South.

“These are my blood relatives, what does that make me?” he recalls thinking.

At that moment, Alvarado learned that his grandmother and himself were Black Latinos or Afro-Latinos, a group that historically has faced prejudice within Latino communities in the United States and abroad.

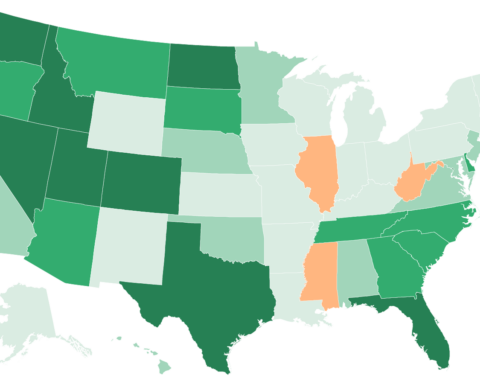

In the last decade, the number of people across the US who identify as Black and Hispanic has increased 11.6%, according to a CNN analysis of census data. The national debate around race along with a growing trend of young Black Latinos embracing their roots in a way that older generations may have not are some of the factors behind the uptick, experts say.

African roots in Latin America can be traced to the 1500s when the majority of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas landed in the Caribbean. Intermingling between Africans, indigenous people and the European Spaniards over generations occurred as a result of the slave trade.

The term traces to the 1970s, when Black activists in Brazil sparked a social political movement to fight for recognition in the country’s census because Brazil — at the time — did not recognize its Black citizens in the census, said Solsiree Del Moral, a professor at Amherst College who studies Latin America and the Caribbean modern history.

Ultimately, defining what it means to be Afro-Latino is personal and can be subjective, multiple scholars and Afro-Latinos told CNN. They have dark and lighter skin, they are fully bilingual or only speak some Spanish and their families are linked to more than a dozen countries. The term acknowledges that Black Latinos face different struggles than other Latinos, especially those with lighter skin, experts say.

In the 2020 census, more than 1.3 million people identified as Black and Hispanic, compared to 1.2 million in 2010, census data shows. Mark Hugo Lopez, director of race and ethnicity research at the Pew Research Center said it is hard to pinpoint exactly what led to the increase.

“It may be because of a change in the census form and the way the responses are coded,” Lopez said. “It may be people becoming more aware of their identity because of things like DNA tests and so forth and it may be because of the way in which US society has discussed and engaged with issues around race and racial equality over the last 10 years.”

Many believe the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and its aftermath led to the rise of acceptance in Afro-Latino identity, but Lopez said the increase was a culmination of years of protests, anger and political polarization that took place long before Floyd’s death.

You don’t have to choose between being Black and Latino

Growing up, Alvarado told others that he was Black. He says it took him years to understand he could equally claim both African and Latin American roots simultaneously.

“I felt like the world was telling me ‘you can either be Black or Latino, but you couldn’t be both,’ and I didn’t know how to explain being both,” he said.

The Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn where he grew up was very diverse, he said, but his lack of fluency in Spanish created a self-imposed pressure to figure out how he could immerse himself in the Latino community.

“I would ask myself ‘am I fully accepted? Do Latinos see me as fully Latino or do they just tolerate me?”’ Alvarado said, adding that no one ever did anything to him to make him feel this way.

Morehouse College, a historically Black all-male university in Atlanta, offered Alvarado a chance to understand his identity, he said. As a student, all but one of his peers saw him as a Black man, he recalls.

“When I came to Morehouse in ’91, there was no ‘oh Joel’s from Puerto Rico.’ Everybody just saw me and said ‘that’s a light-skin Black dude,'” he said.

As a history major at Morehouse, Alvarado researched the transatlantic slave trade as well the expansive history of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. Later, he discovered there were Puerto Ricans on Morehouse’s dive team in the 1950s, so both parts of his identity had a place at his school.

Delving into that history helped him understand who he was as an Afro-Latino, and it gave him a newfound ability to define and vocalize his identity.

“You can be Latino and Black and that doesn’t take away from one or the other, and they shouldn’t have to make you choose between one or the other, you can be both because they’re both representative of who you are as a human being,” Alvarado said.

Racism and discrimination is keeping some from identifying as Afro-Latino

Nydia Guity remembers people calling her “esa morena” in a disparaging tone. The Spanish phrase translates to “that Black Girl.”

Guity, 34, was born and raised in the Bronx to Honduran immigrants. She was one of a few Black students — and one of the few darker skinned students — in her elementary school bilingual class. She recalled Spanish-speakers saying “dehumanizing and disgusting” things about Black people around her because they assumed she wouldn’t understand.

But once it was known she understood Spanish, she said “people suddenly felt comfortable to share things about Blackness in my presence that, for me, are super offensive. It’s like ‘you do know that I’m Black, right?'”

Unlike Alvarado, who was also teased as a child for his racial ambiguity but ultimately came to embrace his full Afro-Latino identity, Guity said she’s exhausted of having to explain to people why she can speak Spanish fluently. For her, saying she’s Afro-Latina erases her Blackness.

“I’m not any less Black because I speak Spanish,” she said.

Instead of calling herself Afro Latina, Guity says she prefers to identify with the African subculture within Honduras called Garifuna. These are the descendants of people from the Caribbean island of St. Vincent who were exiled from the island and relocated to Central American countries like Honduras, Nicaragua and Belize.

Carlos Olave, head of the Hispanic Reading Room at the Library of Congress, and María Peña, a spokeswoman for the Library of Congress, said colorism runs deep in the Spanish language. One example of that is the phrase “mejorar la raza,” which means to improve the race.

“In the popular culture there’s still that belief — whether it’s subconscious or not — that if you marry someone lighter than you, you have a better chance for upward mobility,” Peña said, adding there are certain parts of Latin America where social mobility depends on the complexion of a person’s skin.

A 2019 Pew Research survey highlighted how darker skin color is associated with more frequent experiences of discrimination among Latinos, including people questioning their intelligence, being the subject of jokes and unfair treatment from police.

“Darker-skinned Latinos were more likely across every single discrimination experience we asked about to say that had happened to them in the year before the survey than lighter-skinned Latinos,” said Lopez, the director of race and ethnicity research at the Pew Research Center.

In Puerto Rico, many Latinos struggle to see themselves as Black or of African descent because they link it to slavery, racism and racial violence and many identified as White in the census for decades, said Bárbara Abadía-Rexach, a Latina/Latino studies professor at San Francisco State University.

After more than 75% of people in Puerto Rico identified as White in the 2010 survey, Colectivo Ilé, an anti-racism group of educators and organizers, launched a campaign to encourage citizens to self-identify as Black or more than one race in the 2020 survey.

Abadía-Rexach, who was part of the campaign, said she encountered many people on the island who said they didn’t have to answer the race question because they could write in “Puerto Rican” on the census question about Hispanic and Latino origin.

Puerto Rico was one of the places where the most pronounced growth of multiracial population was reported in the 2020 census. Only 17% of the population chose White as the only racial category while more than half said they were more than one race.

Olave and other experts said there are Latinos who, no matter their complexion, don’t acknowledge their African roots and have a hard time choosing a race.

“I’m not Black, I’m …” Dominican, Puerto Rican, Colombian or any country of origin is common because some people identify more with their experience rather than their race, Olave said.

In the 2010 census, 94% of the US population chose at least one of the five standard, government-defined racial categories — White, Black, Asian, American Indian or Pacific Islander. But among those who identified as Hispanic, 63% selected at least one of these categories compared to 37% who chose “some other race.”

Many respondents offered write-in responses such as “Mexican,” Hispanic” or “Latin American,” according to the Census Bureau.

While some use the term Afro-Latino to merely reclaim their roots, Abadía-Rexach said the term should also be used to challenge the anti-Black attitudes within Latinx communities in the US and abroad.

“People should answer the race question in a political way, how you see yourself, but also how you are treated,” said Abadía-Rexach, adding that she asserts her identity as a Black woman as a means of making a political statement.

There’s a stark difference in generational views of Afro-Latino identity

Growing up, Erica-Antoinette Castillo Slaton, 40, said she always felt like she was “other.” Outside, she was a Black American, but at home, she was the daughter of immigrant parents from Belize and Honduras.

It wasn’t until she turned 18 and left for college that she embraced how different she was, starting with changing the pronunciation of her (maiden) last name.

What was formerly pronounced in English as Castillo — the double L sounds like “jello” — transformed into the Spanish pronunciation Castillo, where the double L sounds like a “Y” like the word “pollo” or chicken in Spanish.

“I decided to no longer assimilate, but to provide it as is in terms of who I was,” Slaton said. Her parents were more concerned with working and supporting their children, she said, than how their name was pronounced.

Changing the pronunciation of her last name led Slaton to eventually see herself as an Afro-Latina woman, something that was unfamiliar to her parents. Slaton said neither of her parents identify as Afro-Latino, even though they could be considered such by definition of their racial and ethnic background.

Her mother identifies as Belizean, Honduran and Garifuna, but has never been in a space to consider whether she was Afro-Latina, Slaton said. Her father identifies as Belizean and Garifuna.

“I think people have the freedom and the right to identify with what they want and it doesn’t have to look a certain way to those of us on the outside,” Slaton said.

While most of the adults who spoke to CNN came to terms with their racial and ethnic identity at a much later age, 16-year-old Nation Shabazz Alvarado is well aware of his diverse heritage.

Unlike his father Joel Alvarado, Nation learned at a fairly young age that his father was a darker-skinned Afro-Latino man from Puerto Rico and his mother was a biracial woman — Black and White — from Alabama.

“It’s confusing for anybody to understand it — especially someone who’s younger — by themselves, luckily I have parents who kind of know this,” Nation said. “They showed me — especially at a younger age — who I am and what I am. That really helped me in the long run, knowing where I fit and knowing who I am.”

When Nation heard the story about his father meeting his grandmother for the first time, he says it confused him and made him wonder what stopped his relatives from showing Alvarado “who he really was” at a younger age. Now, he understands that his grandparents and parents lived during a time where racism, colorism and segregation were more prevalent in both the US and Latin America.

“Racism, in itself, is like a virus. It’s spread until eventually there is antibiotic that takes it out. The antibiotic is the new generation that’s coming in,” Nation said.

“There’s a lot more people like me coming into the world,” he added.