There was a time, not too long ago, when many people could only name one, maybe two, poets — often a long-dead White man named William Shakespeare, Robert Frost or Walt Whitman.

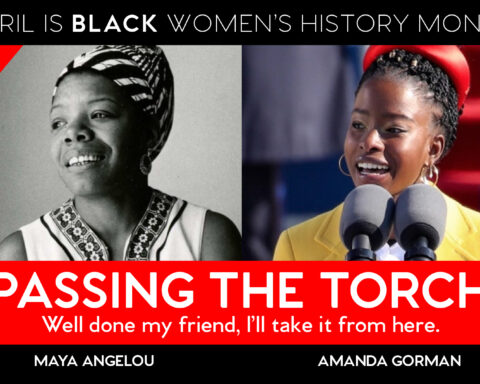

In recent years, though, a shift has occurred. Amanda Gorman, after reading her striking poem at President Joe Biden’s inauguration in January, inked a modeling contract and was invited to the Met Gala. Rupi Kaur, whose poetry first became prominent on social media, has appeared on celebrity-dominated “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” and has a special on Amazon Prime. And, for the first time since 1998, the MacArthur Foundation this year awarded its prestigious “genius” grant to three poets: Hanif Abdurraqib, Don Mee Choi and Reginald Dwayne Betts.

Meanwhile, the Lincoln Center, which houses prestigious artistic institutions like The Juilliard School and the New York Philharmonic, named its very first poet-in-residence this year, Mahogany L. Browne.

Though poetry has always existed and experienced waves of acclaim, the genre is finding new prominence in today’s mainstream collective imagination, stripping itself of its previous relegation to sleepy high school English classes. And, for the most part, poets of color are leading the charge.

In the past, poets of color weren’t always supported

Of course, poets of color — from Phillis Wheatley to Sonia Sanchez and Joy Harjo — have long lived and worked in the United States. But Tyehimba Jess, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and author of “Leadbelly” and “Olio,” recalled a time in the early 1990s when the idea of getting an MFA in poetry, or even being a working artist and submitting to literary journals, was completely foreign to him.

Then, in 1997, Jess happened upon a flier for Cave Canem, a foundation working to support Black poets in the US. At the time, the foundation was in its infancy, and books by Black poets were few and far between, he said. But being in that community is what first motivated him to follow poetry in a professional way.

“What has happened in the last 25 to 30 years, is that there has been a renaissance of Black poetry and a lot of that is particularly due to the kind of work… of organizations and fellowships such as Cave Canem,” Jess said, also naming organizations like Obsidian, a literary magazine dedicated to work from the African Diaspora, and the Watering Hole, a writing retreat for poets of color from the South.

“All of these organizations have been striving and working through really tough times, mostly on the idea of hope and the urgent belief in the power of the word and also the urgency of poets … bringing parts of our history forward that have been neglected, that have been really ignored for so long,” Jess said.

It is the work of these types of fellowships and organizations, Jess said, that has led to the resurgent moment we’re seeing now.

As writers of color are supported in their work, and they go on to become professors or teaching artists or editors or published authors, they create paths for publishing other poets from marginalized groups. It is the embodiment of “lifting as we climb” — and one reason why it may feel like there are so many poets from marginalized backgrounds seeing mainstream success.

More people are reading poetry, mainly people of color

But poetry, as an art form, might also appeal to writers from marginalized backgrounds more than other mediums. Its inherent rejection of any notion of a straight answer creates room for the messiness of the human experience, said poet Ada Limón, whose latest book, “The Carrying,” won the National Book Critics Circle Award. That space might appeal to certain writers over others.

“For those of us in the between spaces … who are not an easy box to be checked, if your identity is a bit slippery, poetry is the place where you can go to explore that, and it becomes a profound interrogation of who we are as humans,” Limón said. “It’s not just one way or the other, no one is trying to be right … instead the poems are saying ‘Yes, me too,’ ‘Yes, this also.'”

And in Limón’s experience, writers of color or those in other marginalized groups have had to resist oversimplifying themselves or their identities — a fluidity that translates more naturally to poetry than, say, a plot-driven novel. Because poetry as a medium resists a summary or a single answer, these writers may be more drawn to it as a form of expression, Limón said.

Limón’s point is reflected in readership data, too. Black Americans, Asian Americans, and other non-White, non-Hispanic groups read poetry at the highest rates, according to data published in 2018 by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Still, overall, more people are reading poetry now than before. In the US, 28 million adults read poetry in 2017, the NEA found, the highest readership ever recorded since 2002. And young people, between the ages of 18 and 24, led the charge, with a readership that doubled when compared to numbers from 2012.

Rupi Kaur — whose second book of poetry “The Sun and Her Flowers” was published in 2017, the year the NEA collected its most recent data — was undoubtedly a part of many young people’s internal poetry repositories. With a career that began in the early 2010s almost through word of mouth, as her signature short poems and drawings were rapidly shared on Tumblr and other social media websites, Kaur now boasts 4.4 million followers on Instagram and has three books to her name.

When asked why she thinks her work resonates, Kaur noted that her writing is very personal and, as a result, her audience can find themselves and their stories in her words.

“I delve into my own life. I talk about how loss, grief, and trauma have affected me. I try to come to terms with that grief by writing poetry. My books are simply a byproduct of that personal self-care process,” Kaur said in a statement to CNN. “And I think when anyone is extremely honest with themselves, that honesty can relate universally.”

Poetry has become more visible in the mainstream

Part of poetry’s growth is due to its increasing visibility with mainstream audiences rather than elite literary circles.

A lot has contributed to this visibility: podcasts such as Poetry Foundation’s “VS” and “The Slowdown,” now hosted by Limón, have helped, as has the increasing popularity of spoken word and slam poetry. The rise of highly popular young poets, people like Ocean Vuong or Morgan Parker, have also played a part, as have growing efforts in grade schools and colleges to teach the works of living poets.

But there’s one thing that’s maybe helped the most: social media.

“For all its faults,” Limón said, “I think that social media has actually done one wonderful thing for poetry, which is provide access and in many, many ways allow for poetry to become completely accessible to anyone.”

It’s much more different than just 15 years ago, she explained. From Instagram accounts like PoetryIsNotALuxury, which posts multiple poems daily from a wide-ranging span of writers, to living poets using social media as a way to spread their work (à la Kaur), social media has changed the way poems reach people.

“That allows everyone, if you’re having a cup of coffee and going through Instagram, to actually have a profound experience with an Audre Lorde poem, or a Lucille Clifton poem,” Limón said. “That kind of one-on-one, in the moment connection with contemporary and ancestral poetry, it’s just huge. And I just don’t think we’ve had that before.”

Another shift, Limón said, has been the acknowledgement of the reader on the poet’s part. When Limón was in graduate school, she felt like poems had to be written for other poets, which changes the poem — making it more abstract, or intellectual, she said. Now, there’s more acknowledgment of a reader who may not be as familiar with poetry, which shifts the engagement of the work to the wider community.

“There’s a certain recognition that poetry is in conversation with real, living humans on the other side of it, not just with the academic side of it,” she said. “That’s been a huge thing.”

She gave an example: Most readers, she said, don’t have to know the reference points of a Shakespearan sonnet to appreciate a contemporary sonnet by Terrance Hayes. But in the past, Limón said there may have been literary references or language within the poem that kept “our poems for poets.”

Poets.org, which publishes a daily poem as part of its series Poem-a-Day, has seen its readerships for both the website and its daily poems grow every year since 2013, said Jennifer Benka, executive director of the Academy of American Poets, which produces Poets.org and Poem-a-Day.

“American poetry — thanks to it being perfect for sharing on social media, the work of poetry organizations nationwide that offer free publications and events, and its diversity of voices — has never been more popular,” Benka said. “During the pandemic, especially, we’ve seen many thousands more readers turn to poetry for comfort and to help make meaning of this moment.”

So far, in 2021 alone, Poets.org has seen a historic spike in traffic, with more than 1 million additional pageviews. That increase in traffic to the website is, in part, attributed to the success of Amanda Gorman at January’s presidential inauguration, and the attention she brought to the art form, a spokesperson for the academy said.

In this way, poetry’s increasing accessibility and visibility have worked hand in hand, leading to rising sales and, naturally, rising interest.

Chantz Erolin, an editor at Graywolf Press — an independent publisher in Minneapolis whose repertory includes works by poets like Jane Kenyon, Tracy K. Smith and Danez Smith — has also noted the “current excitement for contemporary poetry,” calling it “thrilling.”

“The poetry landscape is vast and varied, and the increasing frequency (and visibility) of breakout collections has not only meant an increase in sales, but in more robust opportunities for engagement with poets and the press,” he said.

Though the number of poetry collections Graywolf publishes has remained rather steady, when it last accepted submissions for a single month in 2016, the press received over 4,000 manuscripts, Erolin said.

“It is an amazing time to be alive in the world of poetry,” Limón said. “I really feel that way.”

And though some scholars may argue that the true golden age of poetry was a long-ago era, Limón has a different point of view: The golden age of poetry, she said, is this moment — right now.