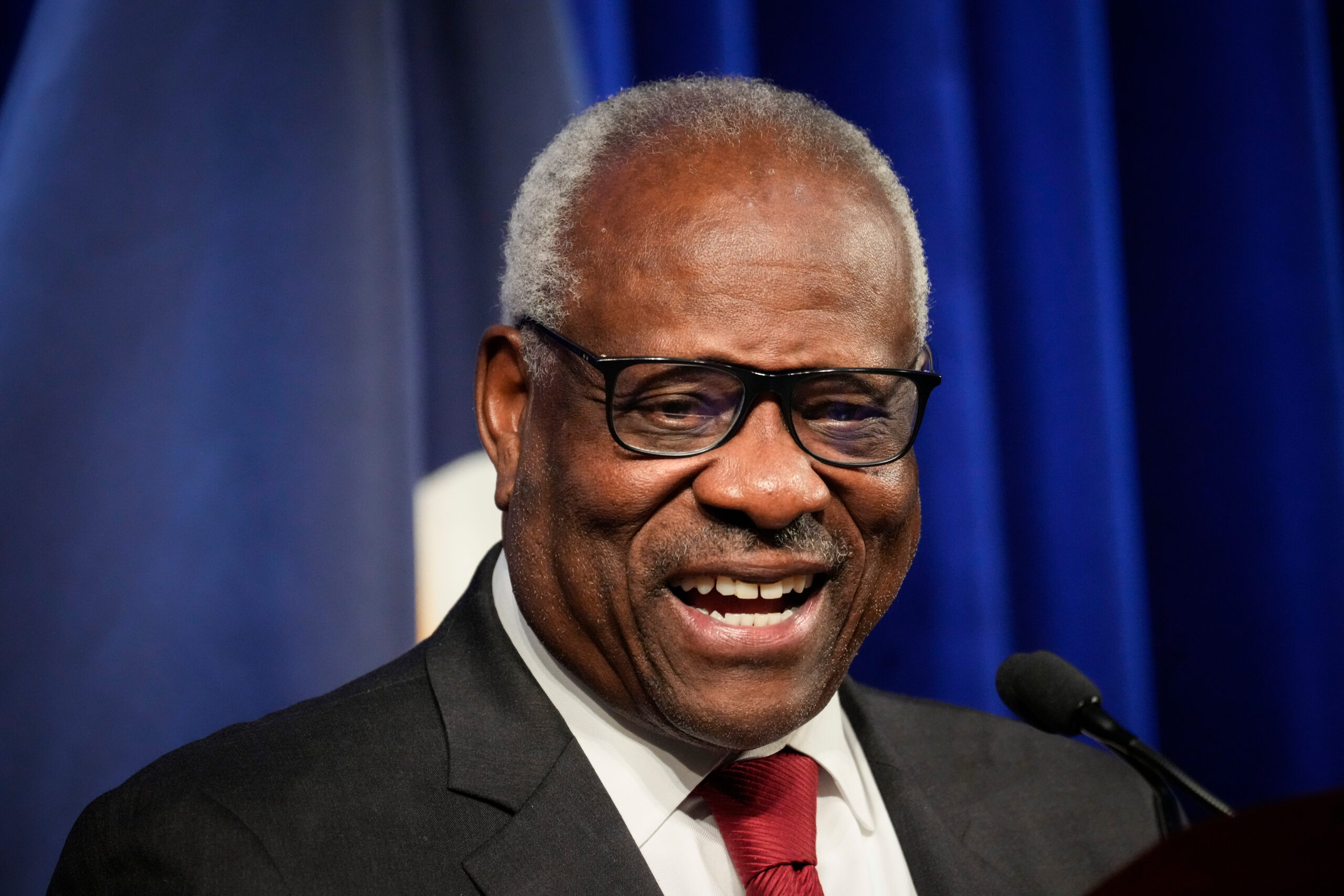

Justice Clarence Thomas‘ unconventional ideas, daring rhetoric and booming baritone have distinguished him from his Supreme Court colleagues over the past 30 years.

From the start, his image at the 1991 Senate confirmation hearings went beyond the world of the law. The 73-year-old Thomas remains a cultural icon, especially on issues of race and sex.

He is an enduring subject of books, movies and all manner of political debate, related to Anita Hill’s accusations of sexual harassment, the expectations of civil rights leaders and Thomas’ own views of racial stereotypes and constitutional conservatism.

Thomas himself has vividly filled in the contours of his persona over the past three decades. He remains one of the most quotable justices in court opinions, extracurricular writings and interviews.

Here is a sampling of some of Thomas’ remarks on flashpoints over the past 30 years.

Race

Thomas is the second African American to serve on the country’s highest court. He succeeded the first, Thurgood Marshall, a pioneering civil rights advocate, but shunned his predecessor’s liberal mantle and support for racial remedies.

Yet Thomas has demonstrated that “race is a core issue” for him, as he told as he told a 2020 audience. It emerges in his personal outlook and his legal emphasis.

In his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” Thomas said he found that a law degree from Yale was different for White and Black students because of “the stigmatizing effects of racial preferences.”

“I knew I’d made a mistake in going to Yale,” he wrote. “I felt as though I’d been tricked, that some of the people who claimed to be helping me were in fact hurting me. … At least southerners were up front about their bigotry: you knew exactly where they were coming from, just like the Georgia rattlesnakes that always let you know when they were ready to strike. Not so the paternalistic big-city whites who offered you a helping hand so long as you were careful to agree with them, but slapped you down if you started acting as if you didn’t know your place.”

Thomas’ experience and ideas about the limits of the Constitution have influenced his ideas as a justice. He opposes government remedies, such as affirmative action.

“I believe blacks can achieve in every avenue of American life without the meddling of university administrators,” he wrote as he dissented in the 2003 case of Grutter v. Bollinger involving a University of Michigan program boosting the chances of minority applicants to the law school. “The Constitution does not … tolerate institutional devotion to the status quo in admissions policies when such devotion ripens into racial discrimination. …. The Law School is not looking for those students who, despite a lower LSAT score or undergraduate grade point average, will succeed in the study of law. The Law School seeks only a facade–it is sufficient that the class looks right, even if it does not perform right. The Law School tantalizes unprepared students with the promise of a University of Michigan degree and all of the opportunities that it offers.”

Soon after his high court appointment, Thomas laid out arguments that judges had too broadly construed the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

“(W)e have devised a remedial mechanism that encourages federal courts to segregate voters into racially designated districts to ensure minority electoral success. In doing so, we have collaborated in what may aptly be termed the racial ‘balkanization’ of the Nation,” Thomas wrote in the 1994 case of Holder v. Hall. “… If one surveys the history of the Voting Rights Act, one can only be struck by the sea change that has occurred in the application and enforcement of the Act since it was passed in 1965. The statute was originally perceived as a remedial provision directed specifically at eradicating discriminatory practices that restricted blacks’ ability to register and vote in the segregated South. Now, the Act has grown into something entirely different. … (W)e have converted the Act into a device for regulating, rationing, and apportioning political power among racial and ethnic groups.”

In a separate vein, Thomas has responded passionately to America’s history of lynching and cross-burning.

During 2002 oral arguments in a controversy over a Virginia law against cross-burning, he told a government lawyer, “My fear is … that you’re actually understating the symbolism of and the effect of the cross, the burning cross. And I think that what you’re attempting to do is to fit this into our (First Amendment) jurisprudence rather than stating more clearly what the cross was intended to accomplish and, indeed, that it is unlike any symbol in our society. … There was no communication of a particular message. It was intended to cause fear and to terrorize a population.”

When the court issued its opinion in Virginia v. Black the next year, Thomas wrote, “In every culture, certain things acquire meaning well beyond what outsiders can comprehend. That goes for both the sacred and the profane. I believe that cross burning is the paradigmatic example of the latter.”

The response to Anita Hill and other personal criticism

When law professor Anita Hill accused Thomas of sexually harassing her when she worked for him, Thomas returned to race during his Senate confirmation hearing.

“From my standpoint as a Black American, as far as I am concerned, it is high-tech lynching for uppity Blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that, unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you,” Thomas said. “You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the US Senate, rather than hung from a tree.”

In a 2020 documentary, “Created Equal,” in which he fully participated, Thomas repeated his racial defense against the accusations of Hill, who is also Black: “Come on, we know what this is all about: This is the wrong Black guy. He has to be destroyed.”

In one of his most emotional public speeches, Thomas in 1998 broadly addressed criticism he has experienced from traditional civil rights groups.

“It pains me deeply, more deeply than any of you can imagine, to be perceived by so many members of my race as doing them harm,” he told the National Bar Association, a predominantly Black organization. “All the sacrifice, all the long hours of preparation were to help, not to hurt … Isn’t it time to move on? Isn’t it time to realize that being angry with me solves no problems? Isn’t it time to acknowledge that the problem of race has defied simple solutions, and that not one of us, not a single one of us, can lay claim to the solution?”

Constitutional conservatism

Thomas, the most conservative justice, is a committed practitioner of “originalism,” which looks to an understanding of the Constitution at its 18th Century origins. But Thomas, across a range of issues, is arguably the most provocative.

He began that way, with no-hedge, no-handwringing opinions. In the 1992 case of Hudson v. McMillian, he dissented as the majority sided with a prisoner who had been beaten by guards while shackled. They broke his teeth and dental plate.

In rejecting the prisoner’s Eighth Amendment claim, Thomas was joined only by Justice Antonin Scalia: “In my view, a use of force that causes only insignificant harm to a prisoner may be immoral, it may be tortious, it may be criminal, and it may even be remediable under other provisions of the Federal Constitution, but it is not cruel and unusual punishment. … Surely prison was not a more congenial place in the early years of the Republic than it is today; nor were our judges and commentators so naive as to be unaware of the often harsh conditions of prison life. Rather, they simply did not conceive of the Eighth Amendment as protecting inmates from harsh treatment. Thus, historically, the lower courts routinely rejected prisoner grievances by explaining that the courts had no role in regulating prison life.”

A New York Times editorial condemning his position was headlined, “The Youngest, Cruelest Justice.”

Thomas responded to some of the fallout from that decision in 1998 before the group of Black lawyers. “I, for one, have been singled out for particularly bilious and venomous assaults. … The principal problem seems to be a deeper antecedent offense. I have no right to think the way I do because I’m Black. Though the ideas and opinions themselves are not necessarily illegitimate if held by non-Black individuals … One opinion that is trotted out for the propaganda parade is my dissent in Hudson v. McMillian. The conclusion reached by the long arms of the critics is that I supported the beating of prisoners in that case. Well, one must either be illiterate or fraught with malice to reach that conclusion… . Indeed, we took the case to decide the quite narrow issue, whether a prisoner’s rights were violated under the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment as the result of a single incident of force by the prison guards which did not cause a significant injury. … Obviously, beating prisoners is bad, but we did not take the case to answer this larger moral question.”

More than a decade later, asked before a different audience at a 2020 Federalist Society event, Thomas adopted a lighter stance. He laughed when US appellate Judge Gregory Katsas, who was a law clerk for Thomas that first court session, asked about the New York Times’ “youngest, cruelest” line.

“I liked that,” Thomas quipped, as he referred to a long-running TV soap opera, “because it sounds like ‘The Young and the Restless,’ brought to you by Tide.”

Beyond his view that the Eighth Amendment should be constrained, Thomas has been most vocal in calling for the reversal of constitutional precedent on abortion rights, the separation of church and state and protections for a free press.

In 2019, he raised states’ interest “in preventing abortion from becoming a tool of modern-day eugenics.”

“The use of abortion to achieve eugenic goals is not merely hypothetical,” he contended in a concurring opinion as the justices declined to take up whether Indiana could prohibit abortions when a physician knows a woman seeks the procedure because of a fetal disability, its race or sex.

“The foundations for legalizing abortion in America were laid during the early 20th-century birth-control movement,” Thomas wrote. “That movement developed alongside the American eugenics movement. … Technological advances have only heightened the eugenic potential for abortion, as abortion can now be used to eliminate concurring children with unwanted characteristics, such as a particular sex or disability. Given the potential for abortion to become a tool of eugenic manipulation, the Court will soon need to confront the constitutionality of laws like Indiana’s.”

Relations in the Marble Palace

Thomas wrote alone in the Indiana abortion case, separating himself from colleagues on the law, as often happens. But Thomas has expressed fondness for fellow justices even in disagreement. He describes the internal debate on cases as “a model of civility.” In his writings, Thomas refrains from the personal shots that others sometimes take.

Despite his rocky early years, Thomas continues to speak fondly of the court in those days under Chief Justice William Rehnquist, with whom he served until Rehnquist’s death in 2005. He recalled in 2020 that when he expressed doubts about the task he faced to Rehnquist, the chief justice told him, “Clarence, your first five years, you wonder how you got here. After that, you wonder how your colleagues got here.”

Thomas and Scalia, who served from 1986 until his 2016 death, were ideological soulmates and especially good friends.

Thomas told me in a 2009 interview: “He loves opera. I prefer blues or jazz. We’re different. I’m a (Nebraska) Cornhuskers’ fan. I don’t think he even watches sports.” Thomas’ wife, Ginni, is from Nebraska, and Thomas has long rooted for the state’s college teams. As for professional football, Thomas made his allegiance clear in 1991 when, after spinning a metaphor involving referees, he told senators, “I’ve been a Dallas Cowboys fan for 25 years.”

“We’re just different,” Thomas continued as he talked to me about Scalia. “We happen to be going in the same direction in the same cases, so we run into each other a lot.”

At a memorial service for Scalia in 2016, Thomas recalled that the two were often alone in their views and criticized: “There were many buck-each-other-up visits. Too many to count. … And there were calls to test an idea or work through a problem. … I loved the eagerness and satisfaction in his voice when he finished a writing of which he was particularly pleased, ‘Clarence, you have got to hear this. It is really good.’ Whereupon, he would deliver a dramatic reading, after fumbling with his computer for a while.”

In a separate interview with me regarding Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Thomas recounted getting beyond an early conflict they had regarding standards for prisoners seeking a writ of habeas corpus to challenge their cases. It was an area of the law that O’Connor, appointed a decade earlier in 1981, had been taking a lead.

Rehnquist had assigned the court’s opinion in the 1992 case of Wright v. West to Thomas. O’Connor agreed with his bottom-line judgment against the prisoner challenging his conviction but declined to sign on to Thomas’ reasoning. She offered a sharply worded, point-by-point critique of Thomas’ position that she believed went too far in restricting prisoner appeals.

When I asked Thomas about those negotiations, he recalled O’Connor’s attitude without rancor, “At first I thought, ‘Whoa, she’s a tough cookie.’ … But they had been working on these (habeas corpus) problems for years and I come marching in like this.'” Thomas pumped his arms vigorously.

He added: “I was the new kid on the block. I was brash. … I just took it like the rookie football player who gets clobbered by the linebacker: ‘Welcome to the NFL.'”