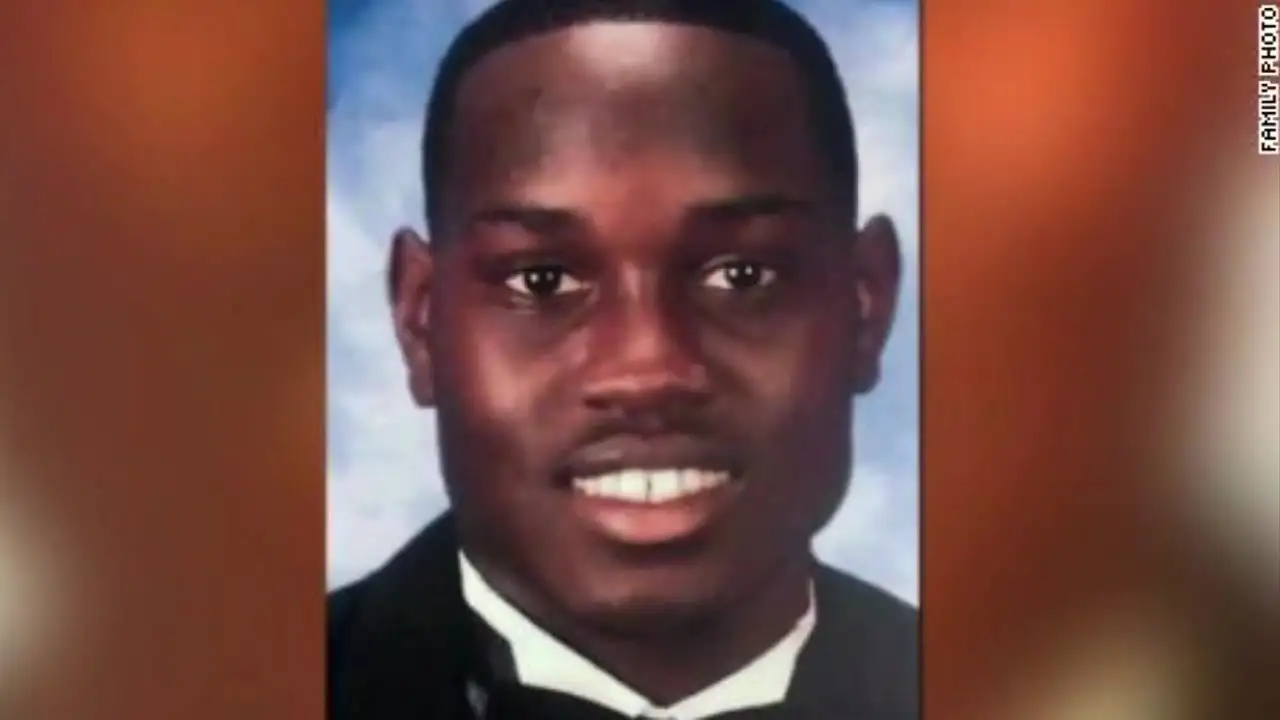

Prosecutors in the trial of three White men charged with the killing of Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery called their first witness on Friday, a police officer, after opening statements by the state and defense attorneys.

Glynn County Police Officer William Duggan testified he responded to the scene after finishing an off-duty job because he was nearby. He told the prosecution that he found a Black male on the ground and saw other people nearby, who he later identified as the defendants.

The officer testified that based on what he observed, he felt Arbery was dead and there was nothing else he could do for him.

In her opening statement earlier Friday, prosecutor Linda Dunikoski argued the defendants tracked down Arbery and cornered and fatally shot him without evidence or knowledge he’d done anything wrong, despite saying they were attempting a citizen’s arrest.

“In this case, all three of these defendants did everything they did based on assumptions,” she said. “Not on facts, not on evidence — on assumptions. And they made decisions in their driveways based on those assumptions that took a young man’s life. And that is why we are here.”

Jurors — 11 White and one Black — selected in a long and grueling process are tasked with deciding whether Gregory McMichael, his son Travis McMichael and their neighbor, William “Roddie” Bryan Jr., are guilty of malice and felony murder in connection with Arbery’s shooting. They also face charges of aggravated assault, false imprisonment and criminal attempt to commit false imprisonment. All have pleaded not guilty.

In their opening statements, attorneys for the McMichaels contended their clients were trying to conduct a citizen’s arrest of Arbery, whom they suspected of burglary after they and several neighbors had become concerned about individuals entering a home under construction. Travis McMichael only shot Arbery in self-defense, they said.

Arbery, 25, was out for a jog on February 23, 2020, near Brunswick, Georgia, when he was shot and killed. Video of the episode surfaced more than two months later, sparking widespread outrage and demonstrations just weeks before the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis set off a summer of nationwide protests against racial injustice.

Bryan, who recorded a video of the shooting, allegedly hit Arbery with his truck after he joined the McMichaels in chasing Arbery. The three men were allowed to leave the scene and weren’t arrested until after the video of the shooting became public.

On Friday, Bryan’s attorney, Kevin Gough, said he would wait to present an own opening statement until after the state presented its case.

Arbery’s mother weeps as graphic body cam footage plays

Duggan, the first witness, testified he responded to the scene of the shooting to find a Black man lying on the pavement and “a couple of other people walking around.”

Duggan’s body camera footage was played in court, appearing to show Arbery lying motionless, face down in the street. The footage showed Duggan turning Arbery over onto his back, his shirt and shorts saturated with blood.

“There’s nothing I can do for this gentleman,” Duggan is heard saying before removing his gloves and wiping his hands with a towel. EMS and fire personnel arrived soon after, the video shows.

Duggan testified the footage was an accurate representation of what he saw and experienced. In response to a question by Dunikoski, however, he said the sound did not capture everything.

Duggan determined there was nothing more he could do for Arbery, he testified, due to “the amount of blood loss I saw on the scene, the lack of rise and fall of the chest, and basically the gaping wound I saw in his chest. There was nothing I could do for him.”

Dunikoski asked Duggan if someone was standing behind him as this unfolded and he responded yes, that Travis McMichael was standing behind him.

According to a pool reporter present, Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, put her head in her hands and wept as the video was shown. One of the jurors was seen shielding herself with her notebook and appeared unable to watch the video as it played, the reporter noted.

The state also showed footage from the dashboard camera of Duggan’s patrol car, which showed another angle of the same scene from a distance. Duggan is seen approaching Arbery, turning him over and crouching beside him.

The officer identified a man pacing back and forth nearby as Travis McMichael, and two other men seen in the dash cam video as Gregory McMichael and Bryan.

During cross-examination from Jason Sheffield, an attorney for Travis McMichael, the officer confirmed Arbery’s eyes were not moving when he checked on him.

Duggan also testified he did not have to use verbal commands to de-escalate the defendants in any way but added that Greg McMichael started to walk toward him “two times” and the officer put his hand out and told him to stay back.

The court adjourned just after 5:30 p.m. Friday following Duggan’s testimony and is scheduled to reconvene Monday morning.

Prosecutors detail shooting and events leading up to it

In the months leading up to the shooting, Larry English, the owner of a home under construction in the Satilla Shores neighborhood, grew concerned about people wandering onto the “open” and “unsecured” construction site, Dunikoski said in her opening statements.

Prosecutors showed the jury surveillance videos of Arbery entering the site, each time wandering around and leaving without incident. Other individuals had also been present on the property, Dunikoski noted. The homeowner had contacted police about the issue several times, Dunikoski said, but told them Arbery — who was unidentified at the time — had never taken anything.

The day of the shooting, Arbery entered the construction site again and was seen by a neighbor who called authorities on a nonemergency line, Dunikoski said. Arbery soon left and ran further into the neighborhood, at which point he was seen by Greg McMichael, who was in his driveway.

“This is driveway decision number one,” Dunikoski said. McMichael went into his house, got his son Travis and both armed themselves — the younger McMichael with a Remington 12 gauge shotgun. They got in Travis McMichael’s truck and pursued Arbery, the prosecutor said.

At this time, neither had any knowledge Arbery had done something wrong, nor that he had been on the construction site, Dunikoski said.

Bryan soon joined the pursuit after he saw an exchange between the McMichaels and Arbery, during which Dunikoski said Travis McMichael asked Arbery where he was coming from and what he was doing. Arbery ran off and was followed by the McMichaels, video showed.

Bryan got in his own truck and joined the pursuit, though he also did not know what was going on, Dunikoski said.

Dunikoski characterized the next few minutes as an attack on Arbery, who turned away from the McMichaels, back down the road toward Bryan. Bryan tried to hit Arbery with his vehicle, getting so close that Arbery left a palm print and T-shirt fibers on the truck, Duniksoki said. Bryan redirected Arbery up the road, back toward the McMichaels.

At one point during the pursuit, Dunikoski, citing comments he made to police, said Gregory McMichael told Arbery, “Stop or I will blow your f**king head off.”

Prosecutors played footage that included the widely seen video of the fatal shooting, which occurred as Travis McMichael and Arbery wrestled over the shotgun.

Arbery’s father left the courtroom before footage of the shooting was played in court Friday, according to a pool reporter present. As the footage played, an audible sob or gasp was heard from Arbery’s mother.

Outside, Arbery’s mother told reporters it was the first time she’d seen the video of the shooting in its entirety.

“I avoided the video for the last 18 months,” Cooper-Jones said. “I thought it was time to get familiar with what happened to Ahmaud in the last minutes of his life. So I’m glad I was able to stay strong and stay in there.”

The “truly, truly tragic” part of the shooting, was that an officer dispatched in response to the initial call by the neighbor was in the neighborhood and heard the gunshots, Dunikoski said.

Despite their defense, Dunikoski said that at no point during subsequent interviews with police did the defendants state they had seen Arbery commit a crime, saying, “The defendants assumed the worst about Mr. Arbery and made their driveway decisions.”

Following the state’s opening, Judge Timothy Walmsley declined to grant a mistrial after defense attorneys complained prosecutors inappropriately raised the issue of the time-lapse between Arbery’s shooting and the arrest of the defendants in her opening statement (Walmsley had previously ruled any mention of this period should not be made in front of the jury).

Travis McMichael had ‘duty and responsibility,’ attorney says

Bob Rubin, Travis McMichael’s defense attorney, said the case was about his client’s “duty and responsibility” to his family and neighborhood, highlighting law enforcement training Travis McMichael received during his time in the US Coast Guard. This training was drilled into him to the point of becoming “muscle memory,” Rubin said.

Rubin similarly outlined the months before the shooting, as Larry English grew more concerned about people on his property and the disappearance of items he believed had been stolen from his boat stored at the site, Rubin said. English had shared that information with neighbors, along with video clips of people on the property.

On February 11, 2020, Travis McMichael had a run-in with Arbery, who had entered English’s house again, Rubin said. Travis McMichael called 911 and said the person he encountered had reached into his pocket, according to audio of the call Rubin played in court. This gave Travis McMichael the belief Arbery could be armed, the attorney said.

Twelve days later, the fatal shooting occurred. When Gregory McMichael, standing in his driveway, saw Arbery, he went inside and told his son, “it’s the guy,” referring to the person seen on English’s property.

“They’re not guessing,” Rubin said. “It’s not some random guy running down the street. It’s the guy, and they turn out to be right.”

While defense attorneys were not contending Arbery committed a crime in the defendants’ presence, Travis McMichael had probable cause to conduct a citizens’ arrest, Rubin said.

Travis McMichael grabbed a shotgun, he said, because he feared Arbery could be armed based on their encounter on February 11. Travis McMichael did not initially show his weapon, Rubin said. But he became fearful when he saw the encounter between Arbery and Bryan (who Travis McMichael did not know), believing Arbery was trying to steal Bryan’s truck, Rubin said.

Eventually, Travis McMichael asked his father when the police were coming. When Gregory McMichael said he had not called the police, Travis McMichael took out his phone, dialed 911 and handed the phone to his father.

“Before the first shot is fired, they call the police,” Rubin said. “That is not evidence of an intent to murder.”

Travis McMichael showed his weapon to try and de-escalate the situation, according to the training he’d received in the Coast Guard, Rubin said. Arbery ran at Travis McMichael, who pointed the weapon at Arbery though he didn’t want to kill him, Rubin said. When he did fire, Travis McMichael had no choice, Rubin said.

“The evidence shows overwhelmingly that Travis McMichael honestly and lawfully attempted to detain Ahmaud Arbery according to the law and shot and killed him in self-defense,” Rubin said.

When Gregory McMichael saw Arbery running past his yard that day, he was certain Arbery was the person seen in the surveillance footage, his attorney Frank Hogue said.

In his opening statement, Hogue pointed to the same events outlined by the other attorneys — the people going onto English’s property, his missing belongings and conversations with the police and other neighbors.

Based on those events, Gregory McMichael’s intent also was to stop Arbery on February 23, 2020, and detain him so police could arrest or speak with him, Hogue said.

For the most part, the events of the case — the “what happened” — would not be disputed, he said.

“The ‘why it happened’ is what this case is about,” he said. “This case turns on intent — beliefs, knowledge, reasons for those beliefs, whether they were true or not. …

“Were there good reasons to believe them?” Hogue asked. “Were there good reasons to believe this young man Ahmaud Arbery had been in this house where things had been taken and that he may have been the person who took them?”

Gregory McMichael’s “suspicions were well-founded,” Hogue said.