The exonerations, after 56 years, of two Black men convicted of the assassination of Malcolm X rights a grave miscarriage of justice and opens new questions about race and America’s criminal justice system.

Spurred by decades of effort by historians and further accelerated by the widely acclaimed 2019 Netflix documentary series, “Who Killed Malcolm X,” the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office reopened the investigation into Malcolm X’s February 21, 1965, assassination. I participated in this film as an on-air historical analyst.

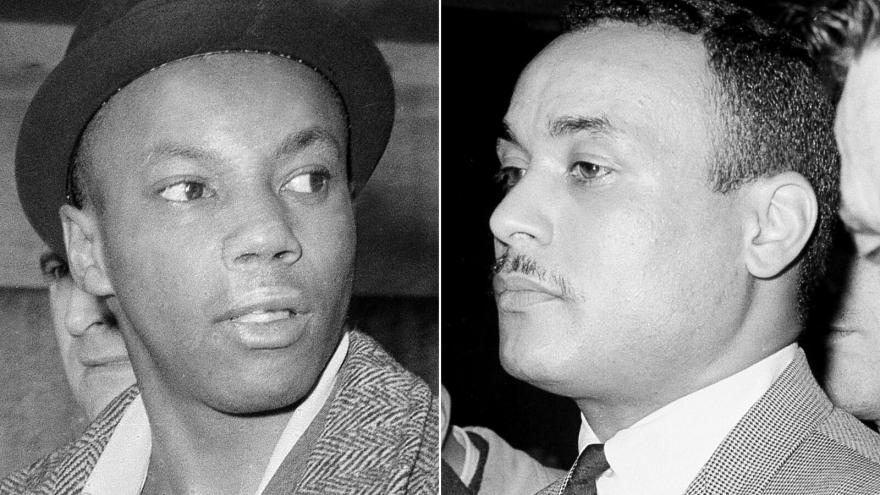

Two of the men found guilty in 1966, Muhammad A. Aziz and Khalil Islam (formerly Norman 3X Butler and Thomas 15X Johnson) have now been exonerated. Aziz, who is 83, was paroled in 1985 while Islam, who was released in 1987, died in 2009 at the age of 74.

According to The New York Times, the 22-month investigation — conducted jointly by the Manhattan DA’s office and lawyers for Aziz and Islam — revealed that after Malcolm X’s killing, the FBI and the New York Police Department withheld evidence that would likely have made a jury find the defendants not guilty.

Aziz, Islam and a third man — Mujahid Abdul Halim (known as Talmadge Hayer and Thomas Hagan) — were convicted. For years, Aziz and Islam said they were innocent; Halim said he took part in the assassination but affirmed the innocence of the other two men at trial and after. According to the New York Times, the recent inquiry uncovered FBI documents including information that implicated others and not Aziz and Islam.

Prosecutors’ notes indicate they failed to disclose that undercover officers were present at the time of the shooting. Police department files also showed that a local reporter got a call the morning of the shooting indicating that Malcolm X would be killed. Investigators also interviewed a living witness who backed up an alibi for Aziz. Overall, the Times reported, the reinvestigation found that had this additional material been shown to a jury, it may well have led to acquittals.

Cyrus Vance, the outgoing Manhattan DA, publicly apologized. “This points to the truth that law enforcement over history has often failed to live up to its responsibilities,” Vance said to the Times. “These men did not get the justice that they deserved.”

On Thursday, New York Supreme Court Administrative Judge Ellen Biben granted the motion to vacate Aziz and Islam’s convictions and expressed regret for the “serious miscarriages of justice in this case.” Vance apologized in court for “serious, unacceptable violations of law and the public trust” and said, “We can’t restore what was taken away from these men and their families, but by correcting the records, perhaps we can begin to restore that faith.”

In the case of Aziz, this exoneration means that he will have witnessed a kind of rough justice in his own lifetime. For Islam these admissions have come too late. Their exonerations join a spate of recent events that illustrate how America’s racial history is being rewritten and how the past continues to inform the present. For instance, Louisiana’s governor is poised to grant a posthumous pardon to Homer Plessy, convicted for boarding a White-only train car and the Black plaintiff in the landmark 1896 Supreme Court case that ratified “separate but equal” as constitutionally permissible.

These exonerations are especially relevant now, not only because they represent another instance of Black defendants receiving unfair treatment before the justice system but because they reframe history at a moment when the failures of that system continue to reverberate through national politics in the United States.

Knowing the fuller truth about his death allows us to see Malcolm X in a new light. Malcolm’s activism honed in on racial disparities in the criminal justice system from firsthand personal experiences. Malcolm X represents one of the most important working-class Black political activists and organizers in American history. Importantly, Malcolm became an ardent prisoner rights activist.

These new revelations about the corrupt investigation into his death helps us to better understand why, in life, Malcolm emerged as a relentless critic of the justice system’s mistreatment of Black America. A formerly incarcerated prisoner himself — turned religious leader, political organizer and public intellectual — Malcolm used the ministry of the Nation of Islam (NOI) to restore the lost promise of scores of Black men and women in postwar America.

After his release on parole from a Massachusetts prison in August 1952, Malcolm shared his story as a former inmate with all who would listen. He never forgot his time in prison nor the inmates who served as mentors, students, counselors and inspiration for his later activism.

And Malcolm continued to fearlessly confront police violence during his years as an activist. The 1957 police beating of NOI member Johnson Hinton helped cement Malcolm’s local legend after he compelled the NYPD to provide the battered Hinton with medical assistance.

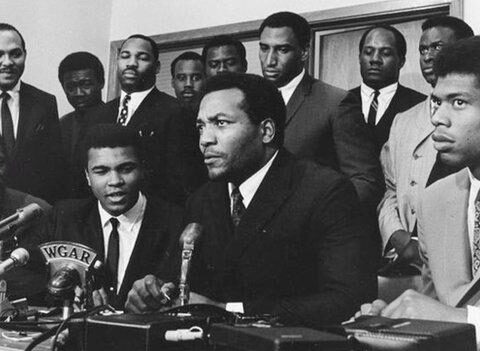

Malcolm’s arrival on the scene with a battalion of NOI members changed minds and hearts in Harlem. Five years later the police killing of Ronald Stokes, an NOI member whom Malcolm considered a friend in Los Angeles, inspired a crusade against law enforcement violence that found the NOI’s national representative crafting coalitions with civil rights leaders to denounce police brutality.

Malcolm’s greatest legacy remains his ability to speak truth to power. His activism echoes across generations and can be seen in the Black Lives Matter movement as well as efforts to end systems of punishment by investing in historically disadvantaged people.

Malcolm X’s 1965 assassination remains one of the most traumatic events of the 1960s. The case remains unsolved, a reflection of not just a racially biased justice system, but a criminally negligent one as well. For 56 years the murder of one of the most impactful political leaders in American history has been an open wound because of what Deborah Francois, a lawyer for Aziz and Islam, described to the Times as “extreme and gross official misconduct.”

This astonishing fact calls into question the integrity of some of the basic institutions within our democracy. The right to a fair trial, presumption of innocence and an investigation led by ethical servants of the public trust is sacrosanct — yet, in large parts of this nation, woefully absent then — and for some, now.

The struggle for Black dignity and citizenship to which Malcolm devoted his whole life continues. The lawyers and staff of the Innocence Project, the filmmakers and team behind the “Who Killed Malcolm X?” documentary, the scholarly work of the late historian Manning Marable, the late journalist Les Payne and Tamara Payne all contributed to this outcome.

Crucial to any understanding of what actually happened to Malcolm X is his public rupture with the NOI and conflict with its leader, Elijah Muhammad, over what Malcolm saw as his former mentor’s hypocrisy over marital infidelity and other transgressions. Malcolm was aware of his lifetime of rumors that NOI was a threat to him. “I live like a man who is dead already,” he told reporters at the time.

For decades scholars activists, and community members have railed against the incarceration of Aziz and Islam as a gross miscarriage of justice. It was this and surely much more.

And despite the welcome results of these decades of work and nearly two years of investigation on top of it, we still have more questions than answers when it comes to Malcolm X’s assassination. Why did law enforcement withhold evidence to convict Aziz and Islam? What role did the FBI and NYPD play? Why did it take 56 years to persuade the Manhattan DA’s office to reinvestigate?

Malcolm X’s legacy continues to haunt America’s criminal justice system in ways that are both sobering and hopeful. The exonerations of Aziz and Islam represent a continuation of Malcolm’s struggle. Malcolm, in so many ways, called America toward the racial and political reckoning it continues to experience. The trials of the White men accused of killing Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia and of Kyle Rittenhouse in Wisconsin illuminate both how far we have come since the civil rights era and the considerable distance we have to travel to achieve racial equity under law not only in theory but in practice.