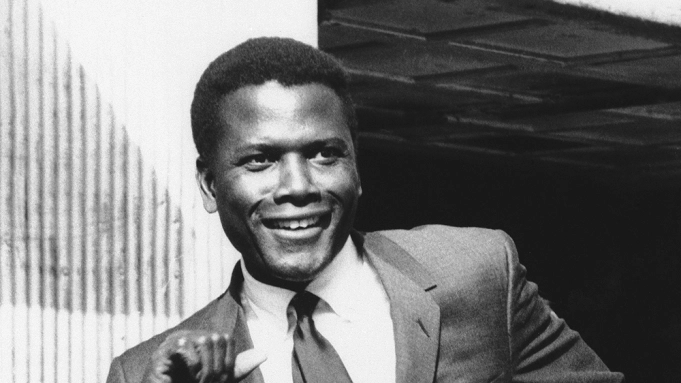

Sidney Poitier, whose elegant bearing and principled onscreen characters made him Hollywood’s first Black movie star and the first Black man to win the best actor Oscar, has died. He was 94.

Clint Watson, press secretary for the Prime Minister of the Bahamas, confirmed to CNN that Poitier died Thursday evening.

Poitier overcame an impoverished background in the Bahamas and softened his thick island accent to rise to the top of his profession at a time when prominent roles for Black actors were rare. He won the Oscar for 1963’s “Lilies of the Field,” in which he played an itinerant laborer who helps a group of White nuns build a chapel.

Many of his best-known films explored racial tensions as Americans were grappling with social changes wrought by the civil rights movement. In 1967 alone, he appeared as a Philadelphia detective fighting bigotry in small-town Mississippi in “In the Heat of the Night” and a doctor who wins over his White fiancée’s skeptical parents in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.”

Poitier’s movies struggled for distribution in the South, and his choice of roles was limited to what White-run studios would produce. Racial taboos, for example, precluded him from most romantic parts. But his dignified roles helped audiences of the 1950s and 1960s envision Black people not just as servants but as doctors, teachers and detectives.

At the same time, as the lone Black leading man in 1960s Hollywood, he came under tremendous scrutiny. He was too often hailed as a noble symbol of his race and endured criticism from some Black people who said he had betrayed them by taking sanitized roles and pandering to Whites.

“It’s been an enormous responsibility,” Poitier told Oprah Winfrey in 2000. “And I accepted it, and I lived in a way that showed how I respected that responsibility. I had to. In order for others to come behind me, there were certain things I had to do.”

As a young actor he overcame enormous challenges

The youngest of seven children, Sidney Poitier was born several months premature in Miami on February 20, 1927, so tiny he could fit in his father’s hand. His parents were tomato farmers who often traveled to and from Florida and the Bahamas.

He was not expected to live. His mother consulted a palm reader, who assuaged her fears.

“The lady took her hand and started speaking to my mother: ‘Don’t worry about your son. He will survive,’ ” Poitier told CBS News in 2013. “And these were her words; she said, ‘He will walk with kings.’ ”

When he was 15, Poitier’s parents sent him from the Bahamas to live with an older brother in Miami, where they figured he would have better opportunities. His father took him to the dock and put $3 in his hand.

“He said, ‘take care of yourself, son.’ And he turned me around to face the boat,” Poitier told NPR in 2009.

Poitier didn’t like Miami and soon headed north to New York, where he tried his hand at acting. It did not go well at first. With limited schooling, he had trouble reading a script.

But he got a job as a dishwasher in a restaurant, where a fortuitous encounter changed his life. An elderly waiter took an interest in the teen and spent nights after work reading the newspaper with him to improve his comprehension, grammar and punctuation.

“That man, every night, the place is closed, everyone’s gone, and he sat there with me week after week after week,” Poitier told CBS News. “And he told me about punctuations. He told me where dots were and what the dots mean here between these two words, all of that stuff.”

Soon after, Poitier landed work with the American Negro Theatre, where he took acting lessons, softened his Bahamian accent and landed a stage role as an understudy to Harry Belafonte. This led to roles on Broadway and eventually caught the attention of Hollywood.

He refused to take roles he felt were demeaning

Poitier’s first movie was 1950’s “No Way Out,” a noir film in which he played a young doctor who must treat a racist patient. That led to increasingly prominent roles as a reverend in the apartheid drama “Cry, the Beloved Country,” a troubled student in “Blackboard Jungle” and an escaped prisoner in “The Defiant Ones,” in which he and Tony Curtis were shackled together and forced to get along to survive. With that 1958 film, Poitier became the first Black man to be nominated for an Oscar.

But for a dark-skinned actor in the 1950s, finding complex roles was difficult.

“(Blacks) were so new in Hollywood. There was almost no frame of reference for us except as stereotypical, one-dimensional characters,” Poitier told Winfrey. “I had in mind what was expected of me — not just what other Blacks expected but what my mother and father expected. And what I expected of myself.”

Early on, Poitier made a conscious decision to reject roles that weren’t consistent with his values or that reflected badly upon his race. He told Winfrey that as a struggling young actor, he turned down a role that paid $750 a week because he didn’t like the character, a janitor who didn’t respond after thugs killed his daughter and threw her body on his lawn.

“I could not imagine playing that part. So I said to myself, ‘That’s not the kind of work I want.’ And I told my agent that I couldn’t play the role,” Poitier said. “He said, ‘Why can’t you play it? There’s nothing derogatory about it in racial terms,’ and I said, ‘I can’t do it.’ He never understood.”

Still, by the late 1950s, Poitier was landing regular acting work. He appeared in the first Broadway production of “A Raisin in the Sun” in 1959 and starred in the movie version two years later. Then came “Lilies of the Field,” biblical epic “The Greatest Story Ever Told” and the drama “A Patch of Blue,” in which his character had a chaste romance with a blind white woman.

Spurred by his friendship with the more outspoken Belafonte, Poitier also began embracing the civil rights movement. He attended the 1963 March on Washington and in 1964 traveled to Mississippi to meet with activists in the days following the infamous slayings of three young civil rights workers.

But Poitier sometimes bristled when interviewers questioned him too much about his experiences with racism.

“Racism was horrendous, but there were other aspects to life,” he told Winfrey. “There are those who allow their lives to be defined only by race. I correct anyone who comes at me only in terms of race.”

A year like no other

Then came 1967, and one of the most remarkable years any Hollywood star has had before or since. Poitier starred in three high-profile films, starting with “To Sir, With Love,” a British drama about an idealistic teacher who must win over rebellious teenagers in a tough East London school.

By this time, Poitier was commanding $1 million a movie, and the filmmakers weren’t sure they could afford to hire him. So they struck a deal to pay the actor scale — the minimum legal amount — in exchange for a percentage of the movie’s box-office grosses. Although common in Hollywood today, it was a radical idea at the time — and a savvy one for Poitier. “To Sir, With Love” became a big hit, earning him a huge payday.

Next up was Norman Jewison’s “In the Heat of the Night,” which gave Poitier his most enduring role. He played Virgil Tibbs, a homicide detective passing through Mississippi when he is detained by a bigoted White police chief (Rod Steiger) as a possible suspect in a slaying. Tibbs reluctantly agrees to stay and help solve the case, and the two men eventually find a grudging mutual respect.

The movie gave Poitier his most famous line — “They call me Mister Tibbs!” — an indignant cry for respect after a demeaning slur by Steiger’s character.

In another memorable scene, Tibbs is slapped in the face by a racist plantation owner and then slaps him right back. Before agreeing to do the film, Poitier requested a script change to add the retaliatory slap and even rewrote his contract to prohibit the studio from cutting the scene.

“And of course it is one of those great, great moments in all of film, when you slap him back,” CBS News’ Lesley Stahl told Poitier in 2013. He replied, “Yes, I knew that I would have been insulting every Black person in the world (if I hadn’t).”

Poitier followed that film with Stanley Kramer’s “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” another message movie about racial tolerance, in which his doctor character must persuade Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn’s characters to let him marry their daughter. The movie was released only six months after the Supreme Court made interracial marriage legal in all 50 states.

However, around the same time some Black people began grumbling that Poitier’s saintly, non-sexualized characters bore little resemblance to the complex realities of African-American life. Black playwright Clifford Mason, in a 1967 New York Times column, argued that Poitier played essentially the same character in every movie: “a good guy in a totally white world, with no wife, no sweetheart, no woman to love or kiss, helping the white man solve the white man’s problem.”

This criticism stung Poitier so much that he retreated to the Bahamas for months.

“I lived through people turning on me. It was painful for a couple years. … I was the most successful Black actor in the history of the country,” Poitier told Winfrey. “The criticism I received was principally because I was usually the only Black in the movies. Personally, I thought that was a step (forward).”

Later he became a director and turned to TV

In the 1970s, Poitier scaled back on acting and turned to directing, which he felt gave him more control over his film projects. He teamed up with his pal Belafonte for the Western “Buck and the Preacher,” his directorial debut. He directed and co-starred with Bill Cosby in the comedy caper “Uptown Saturday Night,” which, along with its spiritual sequels “Let’s Do It Again” and “A Piece of the Action,” featured largely Black casts.

And in 1980, he directed “Stir Crazy,” the Richard Pryor-Gene Wilder prison-break comedy, which became one of his biggest hits.

Although he faded as a big box-office draw, Poitier continued to appear onscreen sporadically into the 1990s, most notably with Tom Berenger in the 1988 action-thriller “Shoot to Kill,” with Robert Redford in the 1992 caper film “Sneakers” and with Bruce Willis and Richard Gere in 1997’s “The Jackal,” his final film role.

He also belatedly turned to television, where he was nominated for Emmys for playing US Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and South African leader Nelson Mandela in two miniseries. He also was considered for the role of President Josiah “Jed” Bartlet on TV’s “The West Wing,” which eventually went to Martin Sheen.

By 2000, Poitier had retired from acting, choosing instead to play golf and pen a memoir, “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography,” in which he described his lifelong attempt to live according to principles instilled in him by his father and others he admired.

In his later years, as Hollywood sought to recognize a man whose example had opened doors for so many other Black actors, the accolades poured in. In 2001, Poitier received an honorary Academy Award for his overall contribution to American cinema. The following year, in accepting his best actor Oscar for “Training Day,” Denzel Washington said, “Forty years I’ve been chasing Sidney. … I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney. I’ll always be following in your footsteps.”

In 2009, President Obama awarded Poitier the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, saying, “It’s been said that Sidney Poitier does not make movies, he makes milestones … milestones of artistic excellence, milestones of America’s progress.”

The Film Society of Lincoln Center bestowed its highest award on Poitier in 2011. Among the speakers praising him was filmmaker Quentin Tarantino, who said, “In the history of movies, there’ve only been a few actors who, once they gained recognition, their influence forever changed the art form.

“There’s a time before their arrival, and there’s a time after their arrival. And after their arrival, nothing’s ever going to be the same again. As far as the movies are concerned, there was pre-Poitier, and there was Hollywood post-Poitier.”