Kristen Berthiaume remembers when George Floyd was murdered, with body cam footage revealing his struggles to breathe and cries for his mother as a police officer knelt on his neck.

Berthiaume couldn’t stop thinking about Floyd, his loved ones, and the Black community as nationwide protests and demands for justice were often met with what she says was blatant racism and ignorance.

After talking with her family about what role they could play in promoting racial justice in their community in Homewood, Alabama, an idea was born.

“Our library was closed due to Covid, but I noticed that books about racial justice were high on bestseller lists,” Berthiaume, 43, told CNN. “We thought opening an antiracist little library at our house could be a way to make these crucially important books accessible to people in our area. We also wanted all kids who came to see themselves represented in the books we offered.”

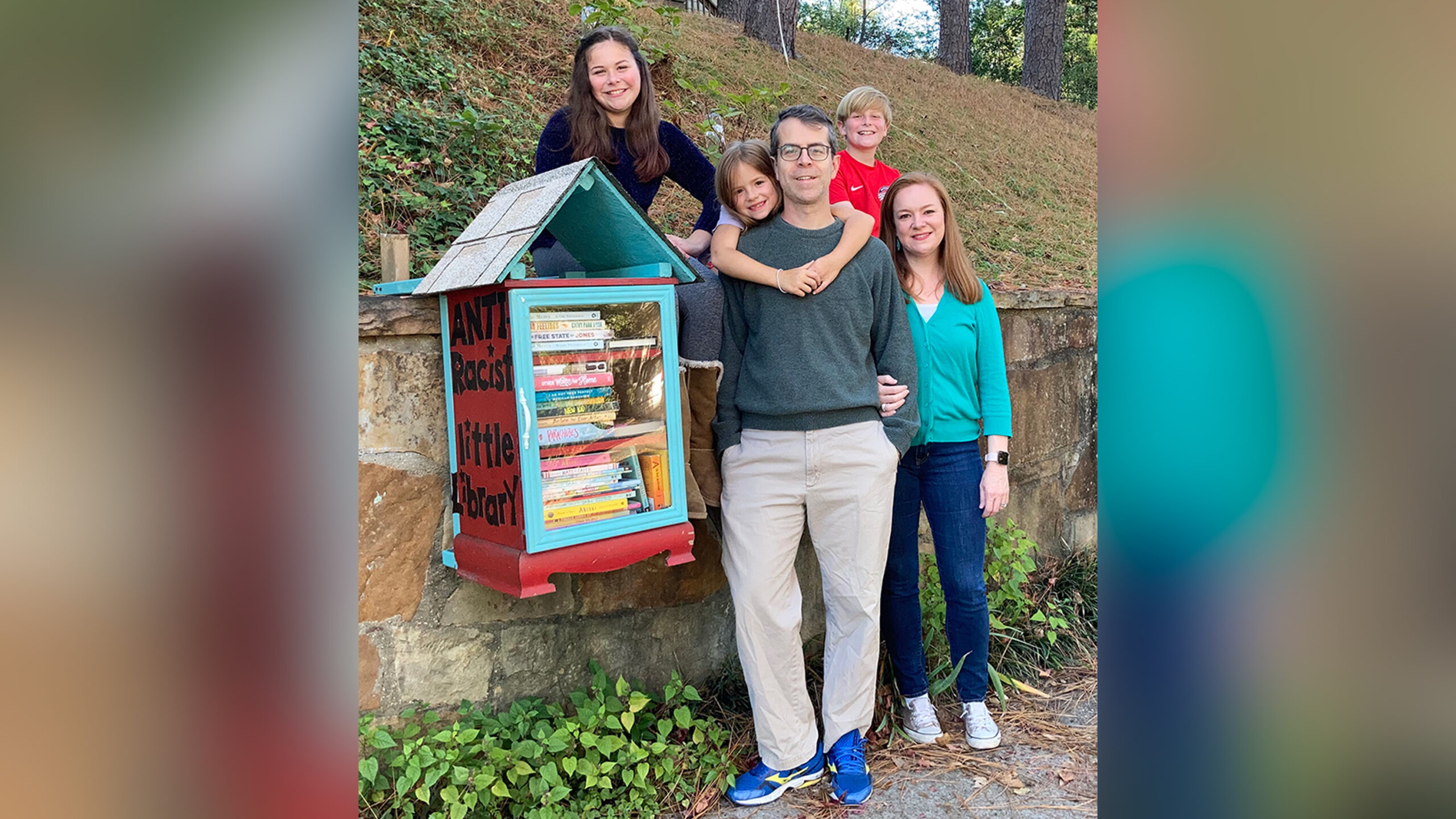

The mother of three children — Emma, Owen and Lily — and her husband built a little library out of discarded red chest drawers. They added a roof and painted it, finalizing it with the words “Antiracist Little Library” on the side.

Then the family got to work, researching and finding books about racial justice, stories with main characters of color, and titles written by authors of color.

After purchasing hundreds of books for children, teens and adults, the library was ready and open to anyone searching for knowledge — or just a good story where all the characters aren’t White, Berthiaume said.

“The response has been incredible. I would estimate around 320 to 350 books have been picked up,” she said. “Our neighbors have all been very supportive. Many people have stopped to say that they enjoy visiting and are glad to have the library in the neighborhood.”

‘Racism is absolutely inescapable’

When Ashley Jones discovered her book, “Reparations Now!,” was included in the Antiracist Little Library, she felt a tinge of hope.

Jones, Alabama’s Poet Laureate, is the first person of color and the youngest person to hold the position, according to Dean Bonner, a historian at Alabama Writers Cooperative.

“As a Black woman in America, racism is absolutely inescapable. It shows up in all the little places and all the big places and all the places you don’t expect. Sometimes it’s in a textbook. Sometimes it’s in a purse grabbed as I walk by, sometimes it’s in a question about my hair, my skin,” Jones told CNN.

“If anyone believes we have even come close to solving issues of racism and discrimination, they’re mistaken. If I’m afraid to go for a run, go buy a snack, go to sleep in my own bed behind my own locked door, we aren’t finished working yet,” she said, referring to recent high profile killings of unarmed Black people.

But the library, and the inclusion of her book, felt like a sign — a small indication that at least some of the world is ready for change.

“Reparations Now!” is a collection of poems about the Black experience and the demand for reparations to Black descendants of enslaved people in the United States.

“We need acknowledgment of wrongs done and still doing, we need empathy and liberation, we need to have the hard conversations,” Jones said. “I let the poetry lead me as I thought through and lived through my experiences with racism and discrimination as a Black woman in America.”

While the shelves of the Antiracist Little Library are full of stories like hers, they also include books aimed at helping people uncover their biases and privileges, such as Ibram X. Kendi’s “How to Be an Antiracist.”

“This library is important because it can maybe show people that some of the tangible steps to doing the interior work needed to address bias and racism can include reading. And it can start in the community,” Jones said.

“I hope this library in Homewood can show other suburban areas that it is part of their responsibility to engage in antiracism,” she said. “And that the books are a beginning — the knowledge gained can then be used in the world beyond the book.”

All the books in the library were stolen — twice

One morning in August 2020, the Berthiaume family drove by their Antiracist Little Library and found that all of the books had been stolen overnight.

“I had completely filled the box the evening before,” Berthiaume said. “It was really shocking and disappointing. We didn’t know their intentions, but we’re the only little library in our area to be stolen from.”

After posting about the theft on their Instagram page, the family received more than 400 donated books and around $1,500 to purchase more.

“We started the library with just enough books to fill it, and now we have an entire storage area so we can always refill the library when it’s running low,” Berthiaume said. “The books were all taken again a few weeks ago, but this time we were able to fill it again immediately.”

“It was a great lesson for our kids to see that, while one person did something destructive, there were way more people out there who wanted to help and build the library up,” she said.

In December, the family’s library became an official partner of the nonprofit group Little Free Library, which provides public bookcases around the US that allow for book sharing within communities.

Following Floyd’s death, the organization launched their own initiative, “Read in Color,” to ensure its mini libraries include diverse authors, stories and characters.

The initiative was launched in October 2020 in Minnesota’s Twin Cities with the addition of 7,000 books that celebrate diverse identities — including Black, Muslim, Native American and LGBTQ voices.

So far, more than 30,000 diverse books have been distributed to over 100 Little Free Libraries across the country.

“We are thrilled to see people across the country moved to share diverse books in their communities — both those who are part of the Little Free Library network and those who aren’t,” Margret Aldrich, spokeswoman for Little Free Library, told CNN.

“Diverse books are vital,” she said. “Everyone deserves to see themselves in the pages of a book, and everyone can learn from perspectives different from their own.”