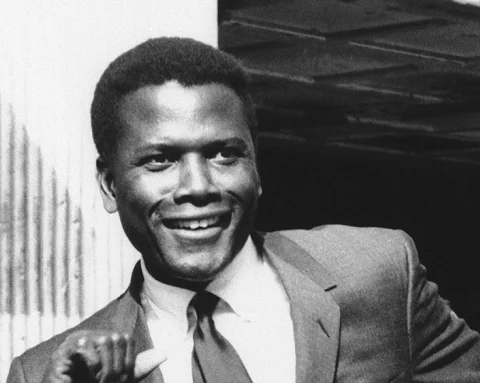

Being the first successful Black male lead in mid-20th-century American movies wasn’t necessarily Sidney Poitier’s greatest achievement. It was the example he set on and off screen to help ensure he wasn’t the only one. Or the last.

Poitier, whose death at 94 was announced Friday, lived long enough not only to reap full and proper acclaim for his groundbreaking body of work as a film actor, but to also witness wave after wave of Black actors, actresses, writers, directors and craftspeople following the path he helped clear for them to win their own Hollywood niches — and their own Oscars to go along with the one he historically won for lead actor for 1963’s “Lilies of the Field.”

As far as other Black male film stars are concerned, let’s put it as simply, and starkly, as possible: Without Sir Sidney Poitier, there is no Billy Dee Williams, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, Eddie Murphy, Forest Whitaker, Michael B. Jordan or, for that matter, that other Michael Jordan, whose ability to parlay his fearsome basketball skills into a cross-cultural, multi-media hyphenate was at least partly enabled by Poitier, who made it safe for Black culture heroes in all kinds of endeavors to connect with Whites as well as other Blacks.

Indeed, when you consider Black male presence in cinema before Poitier’s movie debut in 1950’s “No Way Out” up to a present day — with Black actors as diverse as Washington, Whitaker, Jordan, Delroy Lindo, Idris Elba, Jonathan Majors, LaKeith Stanfield, Leslie Odom Jr, Brian Tyree Henry, Anthony Mackie, Daniel Kaluuya and Aldis Hodge appearing in comparably diverse screen roles — the full measure of what Poitier managed to achieve, practically by himself, is, saying the least, awe-inspiring.

In a postwar America moving steadily, if warily, away from racial segregation, Poitier fulfilled Black movie audiences’ desire for an articulate, youthful and physically magnetic embodiment of their aspirations. He did so while appealing to White audiences for those same qualities — along with a disarming reserve, replete with wry mischief and just enough mystery to keep them guessing what lay beneath his cool, dry exterior.

His stardom emerged from Eisenhower-era “social problem pictures” like “Blackboard Jungle” (1955), “Edge of the City” (1957) and “The Defiant Ones” (1958), where his role as a chain-gang escapee handcuffed to Tony Curtis’s bigoted White convict garnered his first Oscar nomination. With the 1961 adaptation of Lorraine Hansberry’s play “A Raisin in the Sun,” where he reprised the role of put-upon family man Walter Younger that he created in the stage version, Poitier established himself as the most identifiable African-American leading actor in movies.

As he was testing the breadth of his mass appeal and, as film historian Donald Bogle writes, giving “Black Americans a significant reason for going to the movies,” Poitier was aware that he was also testing the levels of racial tolerance. Most of his roles from the 1950s through the 1960s, befitting an era shaped by Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement, were linked by varying tensions between his Black characters and Whites’ reactions to them.

In 1962’s “Pressure Point,” for instance, Poitier’s prison psychiatrist is compelled to check his anger while treating Bobby Darin’s flamboyantly vicious crypto-Nazi convict. In 1965’s “A Patch of Blue,” he was Gordon, a warm-hearted Black man who shows kindness to a poor and blind White girl (Elizabeth Hartman), whose growing love for him is shortchanged, at the end, by him.

This came three years after the role that won Poitier the Oscar for Best Actor (many, including Bogle, believe he should have won for “Raisin”) for “Lilies of the Field,” in which he played a jovial, if world-weary, ex-soldier who runs into a group of refugee German nuns in the Arizona desert in need of their own chapel. Considered light and fluffy even when it premiered in 1963, the movie nonetheless charmed viewers, and Poitier’s charisma and skills were as dominating as ever. Yet almost as many contemporary audiences wince at what they now see as a paradigmatic, anachronistic exemplar of what is now referred to as the “magical negro” movie, in which Black characters’ only real purpose is to carry out near-miraculous salvation for White characters.

Poitier was aware of the tightrope history had asked him to walk: having to widen the possibilities for both his career and his fellow Black performers and maintain his dignity and artistry without alienating Whites in the perilous years of the civil rights era. He was intent on finding roles where race, as such, didn’t matter to the plot, like 1965’s “The Bedford Incident,” or expanded the masses’ expectations for Black actors, as in 1966’s “Duel at Diablo.”

His greatest year, in terms of visibility, was 1967, which yielded the trifecta box-office triumphs of “To Sir, With Love,” “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner,” a romantic comedy about an impending interracial marriage where, in the role of a too-good-to-be-true doctor in the running for a Nobel Prize, he achieved apotheosis as a paragon of virtue who Americans at large would have to be insane to lock out of their living rooms. Yet once again, Poitier’s command of the screen and his delicate radar for nuance kept the saccharine from overpowering the enterprise.

Ironically, as Poitier reached this career peak, his image was under siege by increasing militancy among African American audiences and critics who believed the movement toward racial integration had been overpowered by imperatives for Black nationalism. The late Clifford Mason, a Black cultural critic, wrote a scathing piece for the New York Times that year, “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” which, while acknowledging Poitier’s heroic efforts to break down Hollywood’s once-impregnable race barriers and giving him props for being allowed to slap back at a White southern aristocrat in “In the Heat of the Night,” insisted that Poitier has over 20 years, “play[ed] essentially the same role, the antiseptic, one-dimensional hero.”

More than 50 years have passed and, saying the least, you don’t hear such things being said about Poitier or his oeuvre. That’s partly because Poitier, instead of retreating from or reacting badly to such criticism, continued to broaden both his movie image and his professional palate, giving Black audiences a romantic comedy of their own with 1968’s “For Love of Ivy,” playing a militant revolutionary in 1969’s “The Lost Man,” and directing his own movies, notably with a tandem of comedies written by award-winning playwright Richard Wesley, 1974’s “Uptown Saturday Night” and 1975’s “Let’s Do It Again,” which became “crossover” hits in their amiable depictions of working class Black life.

After his last film in 2001, nearly-75-year-old Poitier was given another Oscar for lifetime achievement. He had reached the kind of iconic stature once reserved solely for such male icons as John Wayne, James Cagney and Cary Grant. That same night, Poitier got to watch both Denzel Washington and Halle Berry receive lead acting Academy Awards, with Berry being the first Black actress to receive the award.

You can’t say for certain, but you have to believe that Poitier believed those latter two events represented a greater, more significant recognition of his long quest for acceptance and achievement than another gold statuette.