By Sholnn Z. Freeman

Each year Black History Month calls attention to the role that leading African Americans have played in shaping American life. Howard University proudly puts the spotlight on the contributions of Dr. Roland B. Scott, whose tireless research and advocacy in sickle cell disease deserve to be remembered. Later this year, the Howard University Center for Sickle Cell Disease will celebrate its 50th anniversary.

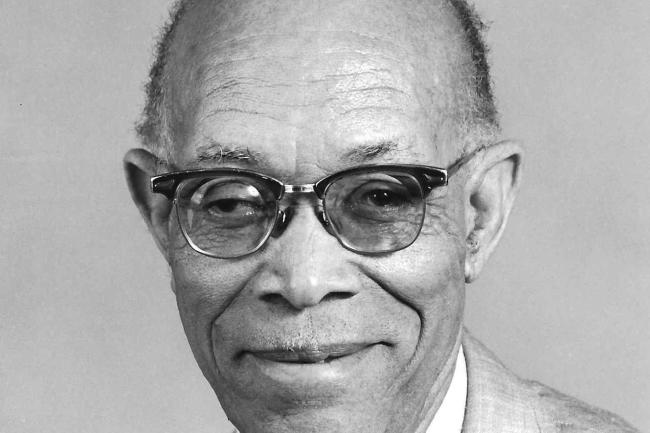

At the time of his death, on Dec 10, 2002, Scott was recognized as the father of research into sickle cell disease. He was a groundbreaking physician and researcher in an era of intense discrimination against Blacks. He was the primary advocate for the National Sickle Cell Control Act of 1972, and founding director of the Howard University Center for Sickle Cell Disease, the first center in the nation devoted to the disease. Scott was the first chair of pediatrics in the Howard University College of Medicine and one of the first two African-American fellows of the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1945.

“Dr. Scott is the person who put sickle cell disease on the map,” says Dr. Oswaldo Castro, who was recruited to Howard University by Scott and later became director of the Center for Sickle Cell Disease. “He put sickle cell disease at the forefront of government health policies.”

Scott was born on April 18, 1909 in Houston, and grew up there and in Kansas City, Missouri. He opted for Howard University for his undergraduate studies based on his mother’s desire for him to be educated in a comfortable social environment. He studied chemistry and went on to earn a medical degree from the Howard University College of Medicine in 1934.

As a medical student, Scott was encouraged to study diseases that affected children and later he decided to focus on pediatric medicine. But Scott had difficulty obtaining a residency in pediatrics because, at the time, hospitals were taking only whites, Castro observed.

“Dr. Scott grew up during a time of discrimination, at a time when it was very difficult to get ahead,” Castro says. “Most people would have been frustrated by the difficulty, but he was able to triumph.”

In 1939, Scott returned to Howard University to an appointment as assistant professor of pediatrics. He spent the rest of his career there. After seeing many children with symptoms of sickle cell disease admitted to Howard University Hospital, Scott began to focus on study of disease despite having no formal training in blood diseases.

Over the next few decades, Scott and co-workers at Howard University published hundreds of articles on sickle cell disease as well as on treatment methods. In 1948, Scott authored a pioneering scientific study on the incidence of red cell sickling in newborn infants. Outside of sickle cell disease, Scott was also the first to report growth and development norms for healthy African American children, which became the basis of nationwide standards.

Among his biggest challenges was persuading the government to provide funding for research. Scott lobbied the U.S. Congress tirelessly and testified on a number of occasions to get the 1972 and subsequent legislation passed. His years of advocacy culminated in the passage of the Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act of 1972, which finally provided nationwide federal funding into the most common genetic disease in the United States.

In 1972, Scott established Howard University’s Center for Sickle Cell Disease. In addition to implementing comprehensive patient care and research into the disease, Scott organized yearly national conferences on blood diseases. His legacy continues now through lectures such that bear his name at Howard University.

The Howard University Center for Sickle Cell Disease remains a key U.S. institute for the study of new sickle cell drugs. The center has a history of treating a high volume of patients and, as a result, has participated in nearly every major clinical trial that has led to FDA-approved medications for sickle cell disease.