By Elias Rodriques

In the 1960s, the Free Southern Theater, an organization founded by a group of activists with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), traveled to a church in a predominantly Black, rural corner of Mississippi. There they staged Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, an absurdist drama about characters conversing as they wait for someone who never arrives. The play may have seemed like a strange choice—who would imagine that Beckett might connect with rural Black Americans in the throes of the civil rights movement?—but it found at least one admirer in civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer. “I guess we know something about waiting, don’t we?” Hamer said from the audience.

Everyone agreed, and as they discussed the play, the conversation eventually turned to slavery and prisons. “We had this incredible discussion with people who barely had a sixth-grade education,” Denise Nicholas, an actress in the Free Southern Theater, said later. And drama—even high-modernist, experimental drama—functioned as political education.

This was the Free Southern Theater’s goal. As cofounder John O’Neal recalled of its creation:

We claimed to be playwrights and poets; yet the political facts of life presented by the situation we first learned of in the South called for a life of useful (political or economic) engagement. How could we remain true to ourselves and our own concerns as artists and at the same time remain true to our developing recognition of political responsibility?

Their answer was a theater group that aimed, as another cofounder, Doris Derby, put it, “to take the plays out to the rural areas, go around and perform out in the cotton fields or in the churches.” They did so out of the belief that, as Nicholas later explained, “the theater, the images, the language, the physicality of it would open doors in people’s minds that they didn’t necessarily need to read a lot of books to get to.” For the Free Southern Theater’s members, bringing the stage to the countryside made political education accessible while enabling artists to participate in politics.

As James Smethurst chronicles in Behold the Land: The Black Arts Movement in the South, the Free Southern Theater was just one of a number of institutions that sought to marry art with local Black Power politics in the South. In a sweeping history of arts institutions from the 1930s to the ’80s, the book tells the story of how the turn to Black Power politics in the ’60s produced a corollary Black Arts Movement that was especially long-lasting in the South. The Black Power and Black Arts movements, in Smethurst’s account, were “so twinned and joined at the hip that it is impossible, really, to tell where one begins and the other ends.” While Black Power generally aimed to develop Black autonomy rather than gain inclusion in American society, the Black Arts Movement sought to produce a culture that valued Black people and used cultural forms like theater to encourage their entry into Black Power politics.

How the Free Southern Theater and other Southern Black Arts Movement institutions were funded is central to Smethurst’s story. As he notes, among the enduring successes of the Black Power movement in the South were its electoral victories, which allowed politicians like Maynard Jackson, the first Black mayor of Atlanta, to allocate funding to Black arts institutions. “The movement in the South,” Smethurst writes, “saw some of the most intense publicly supported institutionalization of African American art and culture of anywhere in the country.” Financing these institutions enabled them to outlast not only the Black Arts Movement’s greatest period of success in Northern cities like New York but also the early stages of post-civil-rights Southern conservatism. Their longevity ensured that these institutions continued to provide essential services and arts instruction to Black communities. In his careful attention to this history, Smethurst reminds readers that building solid institutions can provide a means of outlasting the backlash that inevitably follows radical progress.

Smethurst’s history begins with Marcus Garvey’s early-20th-century Black nationalism and the Black communism of the 1930s, which together, he argues, laid the groundwork for the civil rights, Black Power, and Black Arts movements. In the 1910s and ’20s, Garvey pushed for the creation of a nation in Africa to which all the descendants of enslaved people could repatriate. His biggest organization was the Universal Negro Improvement Association, which likely reached millions of people at its height in the early 20th century. While Garvey was largely based in New York City, the association was especially prominent in the South: In Miami the UNIA organized self-defense, and in New Orleans it supported labor organizing and a clinic providing health care to Black people. It also sponsored a jazz band, foreshadowing the twinned emphasis of later Black nationalists on material change and cultural production.

Garveyism declined in the late 1920s, after Garvey’s 1927 deportation to Jamaica. In its wake, many UNIA members flocked to the Communist Party, which became increasingly prominent in Black politics, especially in the South, where the struggle against the Depression and segregation attracted many new members to the party and its subsidiary organizations. Art as well as labor politics were central sites for Black and white Communists organizing in the South.

Eventually headquartered in Birmingham, Ala., a Communist Party stronghold, the Southern Negro Youth Congress was founded in 1937 both to pursue revolutionary change and to promote Black art. The SNYC’s Puppet Caravan Theatre performed plays about labor and voting rights for Southern farmworkers. It also provided political experience for activists like Ernest Wright, who helped lead the People’s Defense League in New Orleans, which marched for jobs and the right to vote and against police brutality.

Elsewhere in New Orleans, the Dillard History Unit, founded in 1936 and funded by the Federal Writers’ Project, employed the novelist Margaret Walker and contributed to the history The Negro in Louisiana. And in Atlanta in 1942, the visual artist and professor Hale Woodruff joined W.E.B. Du Bois at Atlanta University’s People’s School in creating a program to educate local adults. In these and other organizations, Smethurst writes, the cross-organizational politics rooted in the Communist Party “became the most viable space for building radical African American institutions with a bent toward Black self-determination in most of the South.”

McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare resulted in the persecution of leftists in the early postwar years, but many of these Black cultural workers continued to be active in their communities. In 1941, John Biggers enrolled at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, where he was taught by Elizabeth Catlett, who had worked with the Dillard History Unit. In 1949, Biggers joined Texas Southern University, one of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), as head of the art department, where he pushed students and instructors to interact with local Black communities. In the 1950s, he began painting murals in poor Black areas in Houston. Biggers was not alone in his persistence: Organizers like Anne and Carl Braden in Kentucky and writers like Sterling Brown in Washington, D.C., continued the project of keeping radical ideas and Black organizing alive in a time of segregation and anti-communist repression.

The Black radicalism that informed the Communist Party and many of its subsidiary groups in the South also provided an impetus for Black activism in an era in which the civil rights movement was heating up. In 1949, the demise of the SNYC led several members, including Esther Cooper Jackson, to move north to work for Paul Robeson’s Black Marxist newspaper Freedom (where a young Lorraine Hansberry also worked). In 1955, Freedom succumbed to a lack of funding, in part because potential donors feared FBI harassment (and rightfully so, since the bureau was known to have photographed the license plates of those who attended Robeson’s concerts). But in 1961, Jackson and other former SNYC leaders started the journal Freedomways, which repurposed 1930s radicalism and socialism for the ascendant civil rights movement. Freedomways published older Black radicals like Shirley Graham Du Bois, rising stars like Audre Lorde, and Black nationalists like Sonia Sanchez. In Smethurst’s words, Freedomways “served as a model of what a radical Black political and cultural journal that embodied the principle of self-determination might be…and practically supported the work and institutions of younger Black artists and intellectuals.” In so doing, Freedomways created a bridge between different generations of the South’s Black left and helped to lay the foundations for a new era of social activism and radical arts.

The South proved to be an especially fertile ground from which civil rights organizers were able to harvest the fruit of seeds sown by past radical movements. In the 1960s, the region was home to about half of all Black Americans living in the United States. It hosted a large consortium of HBCUs, which provided shelter for teachers who might have fallen victim to anti-communism at other institutions. And the South provided a home base for SNCC, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and many of the other best-known civil rights groups and organizers. “By the early 1960s,” Smethurst writes, “the South was the terrain of the most vibrant and diverse grassroots Black political activity in the United States, ranging from direct action nonviolent protest to actual armed self-defense.”

Amid the tumult of the civil rights movement, Black artists sought out new means of making their work relevant to Black politics. In 1964, two members of SNCC’s literacy project and a journalist employed by the Mississippi Free Press put their interest in theater to good use by forming the Free Southern Theater. Conceived as a cultural wing of SNCC, the group offered a writing workshop and staged drama for Black Southerners out of its base at Tougaloo College, until police harassment forced it to move to New Orleans. Though rehearsed, the Free Southern Theater’s productions required improvisation because Black Southerners often interacted with the performers, including on one occasion when an audience member stood onstage for much of the play. One cofounder, John O’Neal, encouraged as much when he told the audience, “You are the actors.” The theater group may have read the lines and provided the set, but poor Black Southerners were the actual protagonists, and their lives were the central dramatic arc.

Like many radical Black organizations in the mid-1960s, the Free Southern Theater eventually moved past the integrationist politics of the early civil rights movement and began to concentrate on developing Black culture. This focus on cultural nationalism was occasioned in part by the arrival in 1965 of Tom Dent, a New Orleans native who had left the South for New York. In his time in the North, Dent had participated in Black cultural and political organizations whose members included Maya Angelou, Ishmael Reed, Amiri Baraka, Harold Cruse, and Archie Shepp. But Dent had grown frustrated with the factionalism of many Black Power and Black Arts Movement activists in New York and decided to return to the Big Easy to help bring their ideas (but not their infighting) home. Once there, Dent soon fell in with the Free Southern Theater, and through his extensive contacts the group garnered new financial, personal, and institutional support. The following year, Dent became chairman of the theater’s board and facilitated its move from “an integrated civil rights institution,” Smethurst writes, “to a more self-consciously Black theater with a strong nationalist bent.” This change meant the departure of the group’s white members, but it also provided new possibilities. Under Dent, the Free Southern Theater transitioned “from civil rights to Black Arts, from Negro to Black, from serving the folk of the Black South to being emphatically southern in a Black modality.”

Organizations across the South followed a similar trajectory. At Howard University in Washington, D.C., the poet Sterling Brown mentored students who became key organizers in SNCC as well as those who became noted Black Power activists, including Stokely Carmichael, and Black Arts Movement writers, such as Baraka and Toni Morrison. Off campus, the poet Gaston Neal used War on Poverty funds to establish the Cardozo Area Arts Committee, which in 1965 started the New School of Afro-American Thought, an education and cultural center that taught literature courses to nearby residents. Its opening event featured Black artists ranging from the Harlem Renaissance to the Black Arts Movement, from Brown to Baraka. In the following years, it hosted many important jazz musicians, including Sun Ra’s Arkestra and Joseph Jarman. At another HBCU, Nashville’s Fisk University, in 1966, the novelist John Oliver Killens organized the Black Writers Conference. Though Baraka was not among the participants, “the new militant nationalist writing was a specter haunting the conference,” Smethurst notes. In time, that specter made itself felt.

In the late 1960s and the early ’70s, Black Power radicals and artists opened new institutions and transformed older ones to marry the arts and politics. At the 1967 Black Writers Conference at Fisk, Baraka dominated the proceedings, while several older Black writers, including Gwendolyn Brooks, championed the Black Power and Black Arts movements. That same year, one of Brown’s mentees, Charlie Cobb, visited the pan-African Parisian bookstore Présence Africaine, which inspired him to create a Black nationalist bookstore, Drum and Spear, in D.C. with other SNCC alumni in 1968. Another of Brown’s mentees, A.B. Spellman, moved from New York to Atlanta, where he joined Morehouse professor Stephen Henderson and the historian Vincent Harding in forming what would become the first Black think tank, the Institute of the Black World, which they founded in 1969. And though the Free Southern Theater stopped its tours that year, in part because of diminished funding, its mission of spreading Black culture and inspiring Black people to create their own cultural institutions was sweeping the South.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 and the Black uprisings across the nation that followed pushed these organizers to reconsider the relationship between their institutions and local Black communities. At the newly founded Drum and Spear, Cobb and others hosted political meetings, classes, and readings, including poetry by Gaston Neal. Drum and Spear Press also reprinted C.L.R. James’s 1938 A History of Pan-African Revolt and a translated collection of Palestinian poetry, Enemy of the Sun. Elsewhere in the city, James Garrett, whose family had a history of radical organizing and who had helped found the Black studies program at San Francisco State, began running the Black studies department at the newly opened Federal City College. There, he hired Cobb and other SNCC alumni involved with Drum and Spear. As Cobb recalled:

The question of black education turned on the question or issue of what you were going to do with your education once you finished…. The question you had to confront as a college student was, “Upon graduation, how am I going to use my education for the black community?”

This pedagogical philosophy reoriented many disciplines, from science to literature, toward practical means of serving Black people. Though clashes with administrators led Garrett and others to leave Federal City College and establish a community school, the Center for Black Education, their new approach to the academy influenced other institutions.

Where D.C. became a hub for rethinking Black education, New Orleans served as a locus for rethinking Black art. In 1968, the Tulane Drama Review, edited by onetime Free Southern Theater member Richard Schechner, published its landmark “Black Theatre” issue. Among the offerings was Larry Neal’s foundational essay “The Black Arts Movement,” which described the movement’s ongoing efforts as the cultural wing of Black Power. If the Black Arts Movement sought to create culture that aided autonomous political efforts, as Neal suggested, the Free Southern Theater put that theory into practice. At the time, its theater troupe formally separated from the group’s writers’ workshop, BLKARTSOUTH, then under the leadership of Dent and Kalamu ya Salaam. “For Black theater to have viability in our communities we must have a working tie to those communities,” Dent wrote of the group’s mission, “something more than the mere performance of plays now and then.” Consequently, BLKARTSOUTH was composed entirely of New Orleanians, presented their original work, and primarily cast residents as actors. By valorizing the workshop over the production, BLKARTSOUTH embodied a defining trait of the Black Arts Movement: It valued “process over product.”

Groups across the South likewise experimented with creating new institutions to develop Black culture and political thought. In 1969, the Institute for the Black World began running seminars in Atlanta. “We were trying to put forward the idea,” Vincent Harding later recalled, “that Black scholarship and Black activism were not meant to be separated…and that all of that should be permeated by the arts as well.” Members of Duke University’s Afro-American Association followed through on Harding’s goals in Raleigh-Durham, when protests on campus led them to found Malcolm X Liberation University, which aimed to provide an alternative education for Durham’s Black residents, including Duke students seeking refuge from a violent campus. And in Nashville in 1970, HBCU faculty and staff founded People’s College to teach political and cultural analysis in ways that applied to everyday life. They did so because they saw educating Black people and creating a unique Black culture as essential to building Black nationalism.

As the Black Power and Black Arts movements progressed across the South, they increasingly directed their energy toward electoral campaigns as well as the arts and education. In his 1970 “Coordinator’s Statement,” delivered at the founding convention of the Congress of Afrikan Peoples in Atlanta, Baraka emphasized the importance of voter registration and mobilizing the Black vote. Art played a key part in that effort, with singers like Stevie Wonder, James Brown, and Isaac Hayes supporting Kenneth Gibson’s successful 1970 mayoral campaign in Newark. And these electoral victories, as Smethurst notes, also helped the Black Arts Movement by giving “Black people the administration of political apparatuses with significant control over material resources not before available to Black Power and Black Arts groups.”

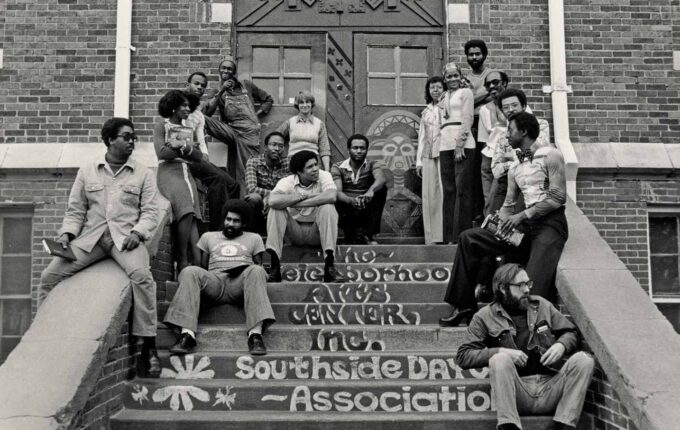

Perhaps nowhere was the importance of electoral victories to bolster the Black Arts Movement more on display than in Atlanta. Following his election in 1973, the city’s “culture mayor,” Maynard Jackson, pledged better funding for the arts. His former speechwriter Michael Lomax led that effort: In 1974 he, the poet Ebon Dooley, and another Jackson campaign staffer and writer, Pearl Cleage, founded the Neighborhood Arts Center, which provided arts education and hosted theater groups in a working-class Black neighborhood. Lomax also helped the writer Toni Cade Bambara secure a position as a writer in residence at Spelman College, another HBCU. In 1975 Jackson appointed Lomax as director of cultural affairs, a position through which he continued financing Black Arts Movement institutions; and in 1978 Bambara, Dooley, and Alice Lovelace founded the Southern Collective of African American Writers, which the Neighborhood Arts Center hosted. In 1979 Lomax helped establish the Fulton County Arts Council, which funded Black Arts Movement organizations throughout the county. By gaining control of the government’s spending power through the vote, politicians like Lomax and Jackson, and artists like Bambara and Dooley, developed Atlanta into a hub for radical Black culture.

Regional collaborations bolstered these efforts. As the Free Southern Theater and BLKARTSOUTH unraveled in the early 1970s, Dent turned his attention to arts organizations in the South more broadly. He had “a great dissatisfaction,” he later recalled, “with the situation in the early ’70s, because I knew that what they were doing in New York was about on the same level with us, but we just didn’t have any money.” Hoping to gain greater recognition and funding, Dent founded the Southern Black Cultural Alliance, which held yearly business meetings at which various organizations could learn from one another how to solve their problems. The alliance also held a yearly conference that brought Black theater troupes and artists across the South to perform. Dent, Salaam, and others then wrote about the conference for a variety of magazines—most notably Hoyt Fuller’s Atlanta-based First World, which replaced Black World—as a means of garnering new exposure for their work. By helping artists across the South, the Southern Black Cultural Alliance aided many Black Arts Movement groups in surviving difficult times.

Unfortunately, many of these organizations, in Atlanta and in the South more generally, faltered as the federal government scaled back its local funding in the 1980s. In the same year that Ronald Reagan was elected, First World published its final issue. In 1981, when Lomax became chair of the Fulton County Arts Council, the federal government defunded the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which had supported many local arts organizations; its 1982 replacement, the Job Placement Training Act, funded far fewer theaters than CETA had. The Reagan administration also provided fewer community block grants, while increasingly conservative Southern state legislatures slashed the funding for Black Arts organizations. Though some managed to persevere, many others had to change their political mission to survive. But as Smethurst reminds his readers, these organizations would have shut down much earlier had they been in other regions; their difficulties in the 1980s after surviving many other conservative turns was less a mark of failure than it was a sign of success.

In Behold the Land, Smethurst demonstrates that decades of organizing and institution building, from the Garveyite years and the Popular Front to the civil rights movement, helped preserve a Black radicalism in the South that eventually became central to the Black Arts Movement in the region. This radicalism was passed on both directly, as when SNYC members published Black Arts writers in Freedomways, and indirectly, as when the Southern Black Cultural Alliance provided a forum for Black Arts Movement workers to collaborate. But in all cases, the Black Arts and Black Power movements were driven by the goal “to build a new culture of Black cooperation and self-determination.” Doing so through the arts had the potential to reorient Black political relations toward a collective building of Black autonomy. “The great strength of Black Arts, its grassroots character, makes it hard to grasp,” Smethurst observes. “Black Arts activities and institutions appeared in almost every community and on every campus where there was an appreciable number of Black people.” By following some of the lines of Black Arts networks, Smethurst gestures toward the broader collaborative endeavors that enabled the movement to gain a foothold in the South and persevere through periods of conservatism.

Through interviews conducted with its surviving participants as well as archival research, Smethurst joins scholars like GerShun Avilez and Carter Mathes in revising the canonical understanding of the Black Arts Movement. Where Margo Crawford has argued, in Black Post-Blackness, that the movement foreshadowed contemporary Black artists in their complication of the meanings of Blackness, Smethurst demonstrates that one way that the Black Arts Movement did so was by building institutions that shaped, if not the contemporary artists directly, then the consumers of the art they produce, the venues in which they produce it, and the communities in which they grew up. This aesthetic legacy also bred a political one: The Black Arts Movement laid the foundation for contemporary community arts organizations, for the use of Black art in electoral campaigns, and for arts education as a Black radical, political practice. Though many Black Power organizations eventually folded, the Black Arts Movement helped spread and institutionalize their ideas.

This afterlife is especially clear in the long-lasting reach of Southern Black feminism. While scholars like Mary Helen Washington and activists like Mariame Kaba have worked to recover the often neglected history and legacy of midcentury Black radical feminists, Smethurst’s account also reminds us of the role of those and other Popular Front radicals in the formation of the Black Arts Movement, especially in the South. Among the SNYC leaders that Smethurst discusses, for instance, was one Alabaman, Sallye Davis. While she worked as a national officer for the SNYC, she was also raising her daughter, Angela, in the intellectual and physical presence of Communist Party members. This early exposure to Marxism, one imagines, influenced not only Angela Davis’s great Black Power autobiography, edited by Toni Morrison and published in 1974, but also her intellectual production and anti-carceral radicalism today.

In a similar fashion, the legacy of many Southern Black Arts Movement organizations lives on in the present. As Smethurst argues, they helped “build new African American cultural institutions in historic African American communities that one finds throughout the South today, and the desire to construct networks between these institutions.” This institutional and coalitional approach ensured that the unraveling of specific institutions did not mark the end of the Black Arts story. If, as Fannie Lou Hamer observed after viewing the Free Southern Theater’s production of Waiting for Godot, Black people know something about waiting, they also know something about the long campaign. Liberation may not come tomorrow, but building institutions might mean that freedom can be achieved in the future.