By Ian Abbey, Ph.D.

I spent a year teaching mostly dual-credit and early college United States history classes in a rural district in northeastern Texas. It was a good year; my supervisors and colleagues, along with the vast majority of my students, were wonderful to work with.

When we covered the Civil Rights Movement, I distributed copies of Louisiana’s voting literacy test from the 1960s and told my students they had ten minutes to complete it. It was a productive lesson because, although none of the students could pass the test, they learned that was the entire point. They then found out more about the barriers that prevented millions of black voters (and poor whites) from exercising their right.

That day, an observer visited to monitor and rate my teaching effectiveness. She seemed uncomfortable with the material and asked something along the lines of “but only some whites supported this, right?” She was a consummate professional and wrote me a glowing review, but it still seemed like an odd question. As if that biracial caste system had not been continually reinforced by white legislators, judges, police officers, and citizens for generations.

Under Texas’ new law, I would not be able to teach that same lesson to a high school class today.

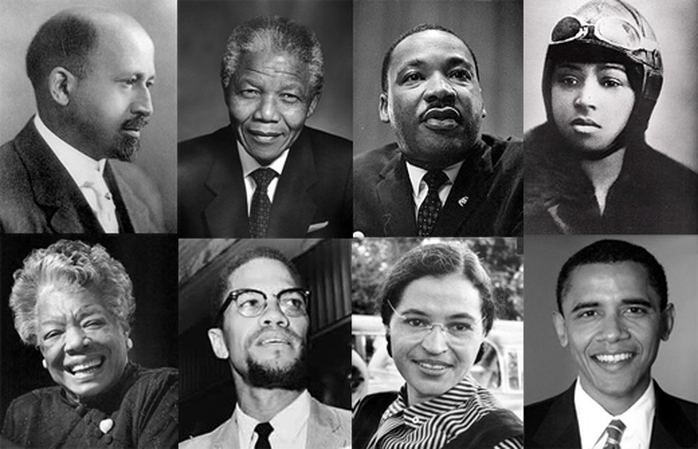

Black History Month is a time for reflection and an opportunity to celebrate the advances black communities have made both today and in the past. Unfortunately, a number of states are making it difficult to teach about those achievements by forcing teachers (and, in some states, professors) to ignore vital context.[1] Instructors cannot effectively teach about triumphs such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Harlem Renaissance, and Jackie Robinson without first teaching about Jim Crow legislation and the de jure and de facto discrimination that existed throughout the country. The Rosewood Massacre seems like an odd act of genocide in a vacuum unless students understand how white Southerners saw the world in the 1920s. Redlining and blockbusting also do not make any sense without considering the depth of bigotry that existed in suburbs from coast to coast.

In Texas, a bill was recently passed that makes it illegal for K-12 public schools to teach anything from the New York Times’ 1619 Project and material that critics might loosely define as critical race theory. Last summer, conservative Texas lawmakers compelled the Bullock Texas State History Museum to cancel a book event because that publication dismantled the fairy tales that many Texans hold about the Texas Revolution.[2] This is ironic considering those same legislators complain about “cancel culture” whenever one of their own gets penalized for spreading misinformation.

In Florida, the process is well underway to censor any classroom instruction that might make students uncomfortable. Florida’s governor, who once signed a bill to raise awareness of the 1920 Ocoee Massacre, is now campaigning against critical race theory in order to galvanize his voter base before the upcoming gubernatorial election. Other conservative states, such as South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Alabama, are methodically adopting similar laws. With midterms coming later this year, it is not hard to conclude that these activities are partly motivated by cynicism and self-interest since they tap into a sense of white grievance.

There have been many recent school board meetings throughout the country that involve outraged parents screaming and threatening violence towards school board members for two reasons. First, they are furiously objecting against mask mandates in schools. And second, because they do not want their children to be taught critical race theory, disregarding the fact that it is not part of the state’s K-12 curriculum and that those parents cannot even accurately define critical race theory. The backlash is not necessarily due to pandemic fatigue or a sincere desire to improve their children’s education, but to white panic.

There is a deep anxiety in many white communities that is not even exclusive to the South. That is why, before the pandemic, those three percent of gun owners who stockpiled half the privately owned guns in the country tended to be a specific category of white men who were anxious that a changing world no longer had a place for them.[3] There is a persistent fear that they will become a minority one day, and the thought of no longer being the default demographic frightens them. Even more, unfortunately, fears of replacement are no longer part of the far-right fringe and have metastasized onto elements of mainstream conservative discourse. The acerbic journalist H.L. Mencken had a point when he wrote, “the normal American of the ‘pure-blooded’ majority goes to rest every night with the uneasy feeling that there is a burglar under his bed and he gets up every morning with the sickening fear that his underwear has been stolen.”[4]

The white majority’s status, beliefs, and views had rarely been questioned for generations. There were certainly exceptions to this since white immigrants from non-Anglo countries were discriminated against, but those immigrant communities were gradually incorporated into the mainstream. White, heterosexual, Christian men, in particular, had the privilege of regarding themselves as the preferred demographic in American social, political, and economic life while other demographics were forced backstage. That arrangement is changing now, and other demographics are asserting themselves. Quite simply, historic atrocities are being exposed, the perpetrators are being castigated, and the communities that were targeted are now calling for more awareness when they had previously been intimidated into silence.

There is a history of persistent discrimination and periodic, intense violence inflicted by reactionary white communities onto their marginalized counterparts, and that must be taught in order to fully appreciate Black History Month. The end of Reconstruction saw unthinking savagery as Redeemers swept into Southern politics and removed blacks from the South’s political world for the next ninety years. In the early twentieth century, WASPs who had whipped themselves into hysteria over non-Anglo European immigration and the Great Migration engaged in wanton cruelty while the Klan became a nationwide organization. As the Civil Rights Movement gained traction, black activists and their allies endured harassment, intimidation, and outright terrorism in their attempt to achieve equality.

At the Capitol insurrection last January, in an obscene display that would not have been out of place in front of a Southern statehouse in 1877, an overwhelmingly white mob launched an assault against the very concept of a multicultural, multiracial, multireligious democracy. The attack failed, but the resentment that drove it has remained a powerful force as the insurrectionists and their sympathizers continue to exercise the rhetoric of the persecuted minority and spread the belief that they are the true victims because they were stopped.[5] The violence was not committed principally by poor rural types, but by middle-class whites who have always given such movements a veneer of respectability.[6] That is what makes those individuals such a danger to the very fabric of the republic.

Even over the past several weeks, a number of HBCUs have been targeted by bomb threats. There is a sordid history of white Southerners attacking HBCUs for daring to challenge white supremacy.[7] Black History Month makes it impossible for that history to be ignored. White communities are now being forced to reckon with their past (and present) instead of being allowed to deny their ancestors’ culpability, dismiss the violence as the actions of a marginal and universally despised white underclass, or shelter behind indifference.

This change taps into a profound sense of discomfort among a significant segment of white parents. That insecurity stems from the fear that their children will reject what they are taught at home. The younger generations are already more likely to have friends of other races and tend to not have issues with interracial marriage.[8] As a result, they are much more empathetic towards different groups and comfortable with diversity. The unease that some parents feel is compounded in small towns and rural areas where social anxiety is exacerbated by blighted local economies and lack of future prospects. The local church congregations are emptying, the grown children are leaving for greener pastures, and the parents and grandparents are left to survey their abandoned towns and theorize that cosmopolitan urbanites who look or think differently from them were responsible for that ruin and then kicked them while they were down.[9] By forcing schools to teach only history that is complimentary to whites – and to white men in particular – these communities are trying to cling to something that will give them a sense of security, even if that means censoring education and literature.

Books that school boards and parents object to for supporting critical race theory or “diverse content” are on the banned list.[11] Now that book bans in Texas, Tennessee, and elsewhere are gaining traction, this is the perfect time to bring exposure to the objectionable titles and encourage students to read them.

Black History Month is an ideal moment to ensure that students and the public at large are aware of this country’s struggles with racism. By doing so, they can better appreciate the effort that marginalized groups – including black communities – undertook to overcome those obstacles. As I tell my students every semester, history should make people uncomfortable. If a history book makes somebody feel good about their country, then they are reading the wrong history book.