Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana

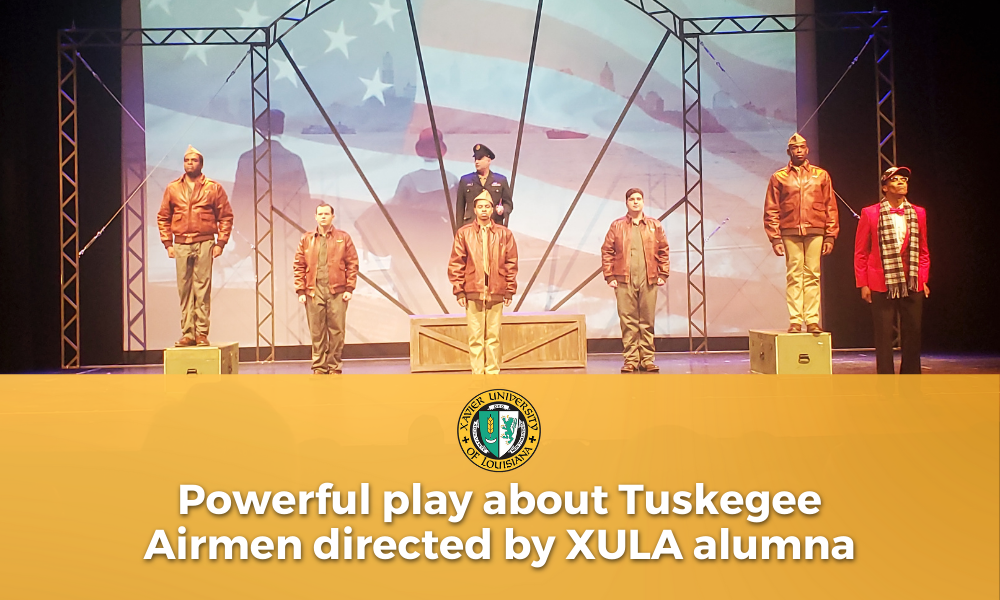

Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA) Alumna Tommye Myrick (‘74) directed the play “Fly,” which opened on February 3 at the Jefferson Performing Arts Center (JPAC) in Metairie, Louisiana. The show ran for two weekends, with the last performance held on February 13, and tells the story of four Tuskegee Airmen set primarily in the summer of 1943.

The Tuskegee Airmen refers to the group of Black pilots trained in Tuskegee, Alabama, to serve as part of the 332nd Fighter Group of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. Written by Trey Ellis and Ricardo Khan, “Fly” depicts their training before combat and uses their experiences as a reference point for other African American trials and triumphs.

The immersion of the play was evident starting in the lobby, where a photographic exhibit called “Souls of Valor” was on display. It featured faces of the Tuskegee Airmen and other Black and African American soldiers of World War II, both in their youth and old age. Seeing the multitude of unsung men and women of color who fought- and in many cases died- for a country that treated them as second-class citizens had a lasting impact on the viewer and set the stage for the performance to come.

The minimal set pieces of the show, including a projector screen, a suspended metal structure, some black wooden boxes, four chairs, and four trunks ensured that all the audience’s attention remained focused on the actors. By utilizing a dancing griot- a West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet, or musician- to express the stifled emotions of the protagonists, the play gives powerful symbolism to the rampant degradation and dangerous discrimination the Black soldiers frequently encountered.

After an opening sequence of projected images of the African coast and an interpretive dance by the Griot, the screen shows clips from the inauguration of President Barrack Obama, a historic moment for the nation. The main protagonist, Chet, appears in his old age attending the inauguration, to which surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen were invited to participate. Almost all of the approximately 330 surviving Tuskegee Airmen attended the real-life 2009 inauguration of the first Black President of the United States.

Chet peacefully laments how proud his fellows would be to see this day, an embodiment of the brighter future that he and his friends dreamed of. He recalls how it felt to be a pilot, a groundbreaking achievement at the time for a man of color. The audience feels his passion as he describes what it was like to fly and watches as time turns back to the era of World War II.

In 1943, Chet is a young man from Harlem, claiming to be 18 years old. The other protagonists, W.W. from Chicago, Oscar from Iowa, and J. Allen of the West Indies are introduced as a small sample of the diverse backgrounds of the actual Tuskegee Airmen. Three other actors portrayed white instructors and fellow pilots, the disdain and prejudice of their characters towards the Black airmen evident from the get-go.

To paraphrase historians, the Black American soldiers of World War II were fighting two wars- one against the enemies overseas and the enemies of racism and mistreatment by their own compatriots and others.

“America has much to learn from these voiceless brave souls who fought to keep America free.” Myrick recently stated to news outlets. “Despite a system of government that denied them full citizenship, they heeded the call to arms to defend and protect this country. Their sacrifice and courage must never be forgotten, omitted, or diminished.”

The audience witnesses the trials the four enlistees face, including many of their peers being “washouts,” with blatant prejudice contributing to much of their failings. J. Allen is one of those that becomes a “wash out” later in the play, and his heartbreaking cries as he is sent home tears at the soul.

Another challenge the men have difficulty overcoming is their own differences. Though a small representation of the diversity among the real Tuskegee Airmen, the protagonists come from very different backgrounds, geographical locations, cultures, and life experiences, leading to some disagreements. However, they soon realized that they could not allow the divisive actions of their prejudiced commanding officers to cause them to fight among themselves.

The abrasive W.W. from Chicago, easily the most pessimistic of the group, is the character to voice this realization aloud after he is named the “leader” of their subunit. After a few scuffles, W.W. eventually becomes determined to put aside the internal conflict and blossoms as a capable and effective leader.

Despite disagreements and differences, the pilots chose to find brotherhood and solidarity, focusing on being the best. Though not said directly in the play, the Black aviators had to prove themselves the best just to be acknowledged by their white commanders and peers.

Oscar, a self-proclaimed “race man,” is the most obvious example. He joined to pave the way for future Black pilots and prove wrong racist assertions made about the incapability of Black individuals. He often proclaims that his actions are “for my people.”

Meanwhile, the Griot is used to subtly expand the reactions and emotions of Chet and the others, especially when they go for their first “flight.” During this act, the Griot speaks his only lines during Chet’s flight, and as claimed by Myrick, the power of his words is unforgettable. His monologue embraces the beauty of what it was to see the world from the clouds, transferring to the audience the irrevocable passion and drive of the airmen who followed their dreams, no matter the obstacles.

It is revealed that Chet is underage and forged documents to enlist. Though the others are furious that his actions put them all in danger of being dismissed, they acknowledge his fervor and skills as a pilot. Oscar, Chet, and W.W. finally stand proud as they receive their pins marking them as graduates and official United States Air Force pilots.

The audience witnesses as they run missions and save the lives of white pilots. W.W., Chet, and Oscar take glee in revealing their identities as Black Americans, shocking the white flyers. Oscar is killed in action, and the heartbreak of W.W. and Chet is palpable.

The two white pilots that Oscar saved on his last mission come to the barracks of the Black soldiers to express their gratitude and tell them that they chose their unit to accompany them on a dangerous, war-changing mission. Though obviously uncomfortable with the Black airmen, the soldiers briefly bond and throw their written fears symbolically into a fire. The white pilots ask that the Tuskegee flyers get them safely home, but W.W. clarifies that he is not doing this for them- instead, like Oscar and in the memory of his fallen friend, he is doing this for his people.

They succeed in their mission, but W.W. is severely wounded. Chet struggles to keep his friend awake and alive as they race back to base when the familiar voice of J. Allen greets them. The two have made it. The audience is then brought back to the current era, and an elderly Chet is seen again.

History tells us what the play skipped over; despite all their contributions, the Black women and men who fought for their country were ushered out of sight, barred from celebrations, and continued to face discrimination and prejudice.

Even in 2000, there was a minimal representation of veterans of color. During the largest military parade in the nation since the end of World War II, held in celebration of the opening of the New Orleans’ National World War II Museum, then called the National D-Day Museum, very few soldiers of color were acknowledged. Myrick’s letter “We Were There,” published in the Times-Picayune Newspaper calling for a boycott of the museum for ignoring the contributions of soldiers of color, would eventually result in a 2001 parade specifically acknowledging the contributions of the soldiers of color during the second World War.

Myrick hoped that the play educated attendees and paid homage to the brave soldiers who fought two wars, one of which is still not over.

This was the play’s first performance in New Orleans.