By Ashleigh D. Coren

1. Amanda Smith

Orator and evangelist Amanda Smith forged a new role for women in the Methodist church in the late 19th century. Some of Smith’s many accomplishments include establishing an orphanage for Black children outside of Chicago, Illinois. She was most well known for her powerful speeches and she ministered to many in England, India, and West Africa.

2. Lynette Youson

Lynette Youson is a fifth-generation basket weaver from a Gullah community in South Carolina. The Gullah are a group of African Americans living in the Southeast who maintain cultural, linguistic, and artistic traditions from West African ancestors. Youson creates decorative and utilitarian baskets. Fanner baskets, like this basket from our Smithsonian American Art Museum, are used to separate rice from its hulls. Youson has woven baskets for more than 45 years, and she teaches her art. She also helps protect coastal habitats where basketry grasses grow, including native sweetgrass (Muhlenbergia filipes).

3. Mary Lee Mills

Captain Mary Lee Mills, USPHS, MSN, MPH, RN, CNM, began her career in public health as a nurse-midwife. In 1946, Mills joined the United States Public Health Service, where she completed tours of duty in Liberia, Lebanon, and South Vietnam. She helped to establish the first nursing school in Lebanon. She was awarded Lebanon’s National Order of the Cedar in response to her efforts.

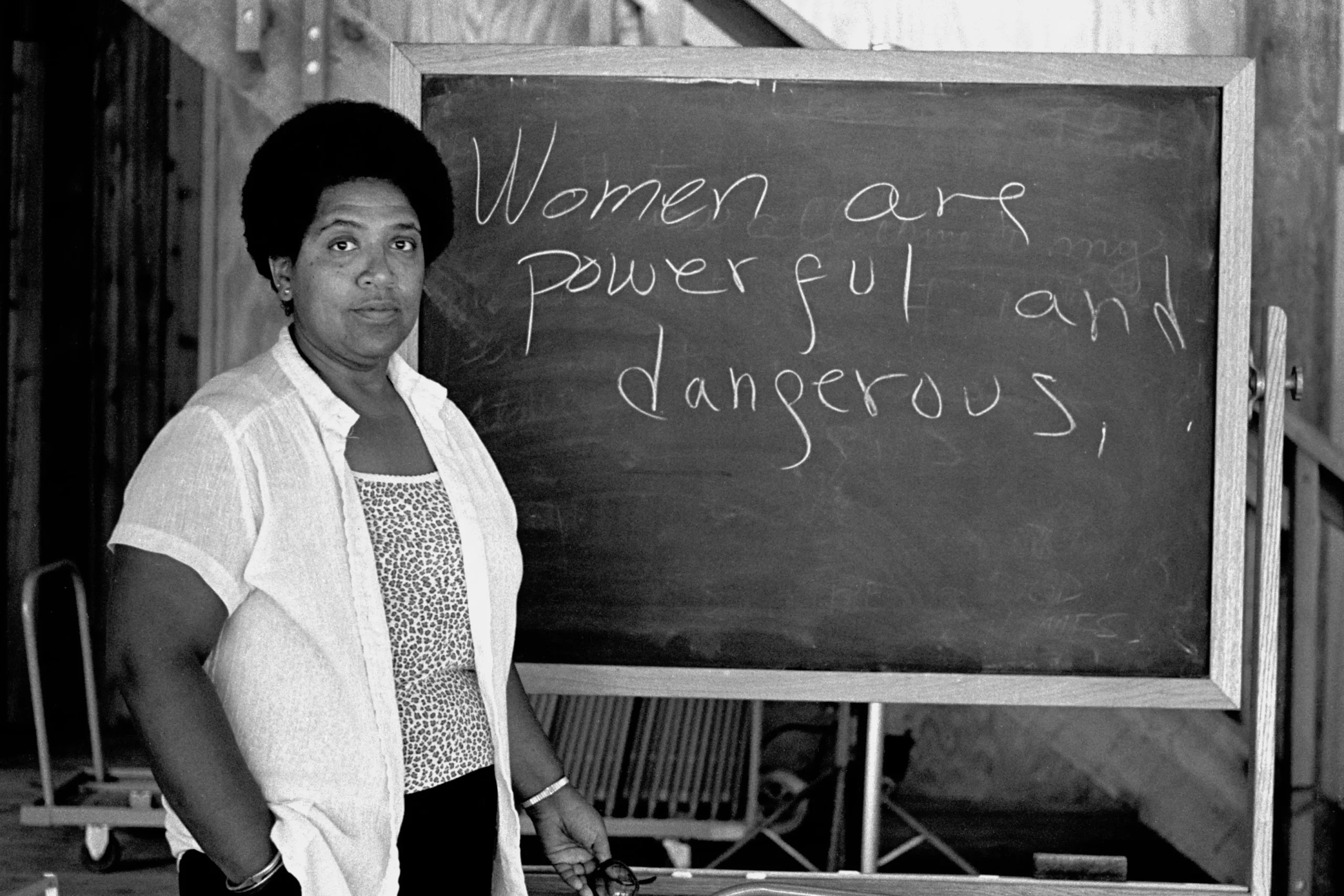

4. Sonia Sanchez

Born on September 9, 1934, in Birmingham, Alabama, Sonia Sanchez has inspired generations of women and African Americans through poetry, teachings, plays, and activism. As a prominent member of the Black Arts Movement, she made a name for herself by centering Black pride in creative expression. In 1975, she joined the English faculty at Temple University, where she taught and mentored young people for nearly 25 years. Her work includes dozens of books, essays, short stories, and other materials.

5. Ruth Temple

Dr. Ruth Temple was a leading figure in public health and focused most of her efforts on improving the lives of Black East Angelenos. In 1918, Temple became the first African American woman graduate of Loma Linda University in California. She went on to found the first medical clinic in Southeast Los Angeles. The community health clinic provided residents treatment for substance abuse, offered immunizations, and focused on teaching health literacy. In 1948, Ruth was appointed director of the Division of Public Health for the city of Los Angeles. A clinic in Los Angeles was named after her in 1983, honoring her legacy.

6. Renée Stout

Artist Renée Stout works in many mediums, including painting, photography, and mixed media installation. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Carnegie Mellon University. Today she lives and works in Washington, D.C. Stout’s work explores healing, spirituality, and divination in a creative and playful way. She creates work as her fictional alter-ego, Fatima Mayfield. Mayfield is an herbalist and fortune teller. “The Old Fortune Teller’s Board,” from the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection, represents the items Fatima would use in her fortune telling practice. For the Hirshhorn Artist Diaries series documenting artists during the COVID-19 pandemic, Stout speaks about the need for joyful moments before lacing up her roller skates for a spin around her studio.

7. Barbara Jordan

Politician, lawyer, and professor Barbara Jordan was an outspoken advocate for social equity. As a young Texan lawyer, Jordan volunteered for the Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy and his running mate, Texan Lydon B. Johnson. Volunteering inspired Jordan to enter politics. After two unsuccessful campaigns, Jordan won a seat in the Texas Senate in 1966. She became one of two African Americans elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1972. In 1976, she became the first African American woman to deliver a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. Jordan retired from politics and became a professor, teaching even after she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and began using a wheelchair. She lived with her companion Nancy Earl for over 20 years.

8. Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, and Allison Russell

Musical group Our Native Daughters shines light on African American women’s stories of struggle, resistance, and hope. Banjo-playing members Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, and Allison Russell draw from 17th, 18th, and 19th—century sources. They reinterpret old compositions and create original new works. With unflinching, razor-sharp honesty, Our Native Daughters use their Black women’s perspectives to confront stories about slavery, racism, misogyny, and empowerment. Their songs call on the spirits of the daughters, mothers, and grandmothers who have fought for justice.