By Fred Frommer

As Jackie Robinson prepared to take the field as the first Black player in modern baseball history on Opening Day 75 years ago this Friday, an Associated Press reporter asked if he had any butterflies in his stomach.

“Not a one,” Robinson replied, with a grin. “I wish I could say I did because then maybe I’d have an alibi if I don’t do so good. But I won’t be able to use that as an alibi.”

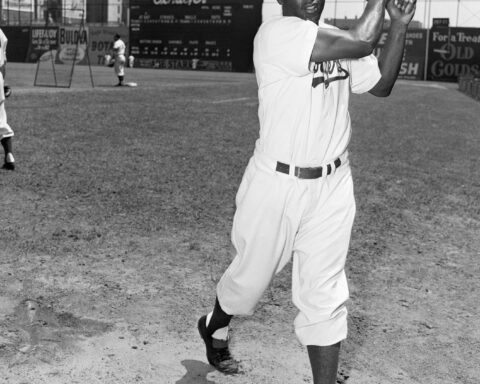

Two years earlier, in 1945, Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey signed Robinson to a minor league contract, after Robinson played a single season in the Negro Leagues. After a stellar year with the team’s top minor league team in Montreal, where he led the International League with a .349 batting average, Robinson was promoted to the Dodgers as a 28-year-old rookie in 1947.

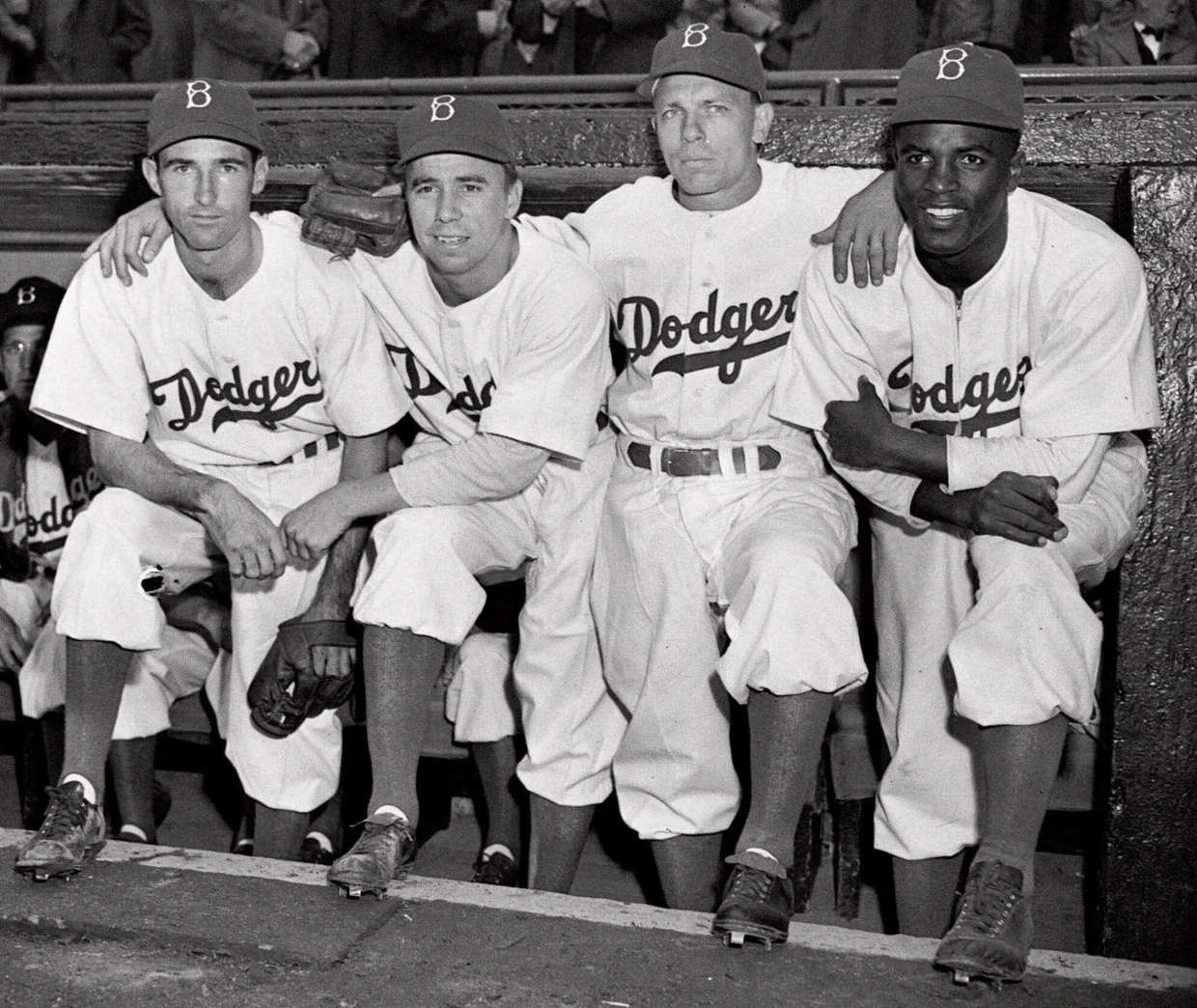

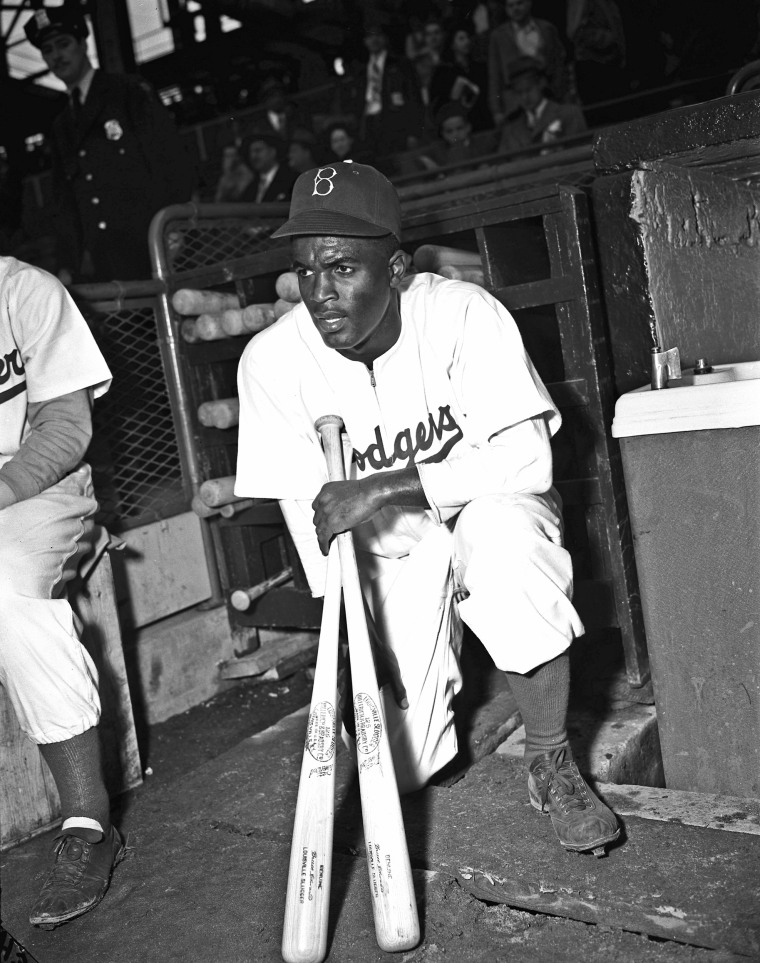

Before his MLB debut on a chilly spring day in Brooklyn, Robinson posed for a photograph in front of the Dodgers dugout shaking hands with interim manager Clyde Sukeforth — the scout who had brought him to meet Rickey in 1945. Both Robinson and Sukeforth are smiling, but on either side of them are glum-faced Dodgers players and coaches.

Some of Robinson’s teammates had organized a petition opposing playing with him. Rickey quickly snuffed out the protest, letting the players know he’d trade anyone who wasn’t on board. It was in that pressure-cooker atmosphere in the dugout that Robinson stepped out on the diamond on April 15 to break baseball’s color barrier.

As the team’s first baseman that day, he saw action right from the start. Boston Braves hitter Dick Culler led off the game with a ground ball to third baseman John “Spider” Jorgensen, who threw to Robinson. As the ball smacked into his glove, fans roared their approval for this routine yet historic out.

That trying first season, Robinson would face plenty of verbal abuse and worse from fans across the country, but on this Tuesday afternoon at Ebbets Field, where half the 26,000 fans were Black, he received a warm welcome. Among his champions in the tiny ballpark was his wife, Rachel Robinson.

“Black fans were so tense, and so enthusiastic — their expectations were so high, and their aspirations were so high — that they just reacted to everything,” she recalled in Ken Burns’s documentary, “Baseball.”

Many fans wore “I’m for Jackie” buttons.

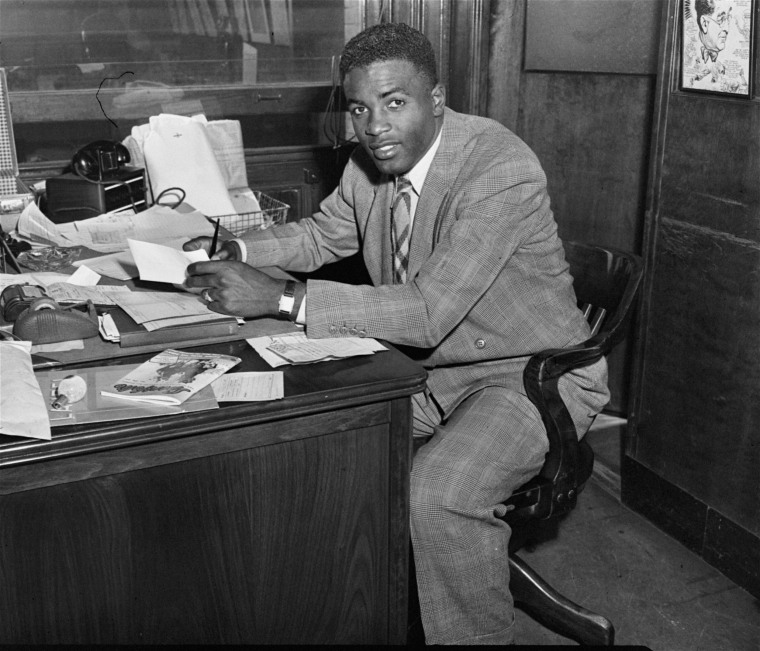

In that morning’s New York Times, columnist Arthur Daley wrote that “Robinson almost has to be another DiMaggio in making good from the opening whistle,” referring to legendary Yankees outfielder Joe DiMaggio. “It’s not fair to him, but no one can do anything about it but himself. Pioneers never had it easy and Robinson, perforce, is a pioneer. … It’s his burden to carry from now on and he must carry it alone.”

Hitting second in the Brooklyn lineup, Robinson came to bat in the bottom of the first inning to more enthusiastic cheers. Fans yelled, “Come on, Jackie,” and “We’re with you, boy,” The Baltimore Afro-American reported.

Facing one of the game’s best pitchers, Johnny Sain, who had gone 20-14 with a 2.21 ERA in 1946, Robinson grounded out to third. Two innings later, he flew out to left field. In the bottom of the fifth, there was more futility, when he grounded into a rally-killing double-play.

“With each failure, a groan went up through the stands as though every man, woman and child were trying as hard as he,” The Baltimore Afro-American wrote.

The dynamic rookie finally made things happen in the bottom of the seventh. With the Dodgers trailing, 3-2, he reached on an error after executing a well-placed sacrifice bunt, and eventually scored the go-ahead run on the way to a 5-3 Brooklyn victory. But his final tally for the day was anticlimactic — 0-for-3.

“I did a miserable job,” Robinson wrote in his 1972 autobiography, “I Never Had It Made.” If fans “expected any miracles out of Robinson, they were sadly disappointed.”

Despite the historic day, major newspapers downplayed it. Both The New York Times and The Washington Post, for example, reported on Robinson’s debut inside the paper, with the Times story barely mentioning him at all, focusing instead on the game. A Times column, also by Daley, headlined “Opening Day at Ebbets Field” didn’t get around to Robinson until the ninth paragraph, describing him as a “muscular Negro … who speaks quietly and intelligently when spoken to.”

“Having Jackie on the team is still a little strange, just like anything else that’s new,” an unnamed veteran teammate said in the column. “We just don’t know how to act with him. But he’ll be accepted in time.”

Robinson would face a barrage of abuse that year — including death threats, players deliberately spiking him, and racial epithets from fans and opponents. But he helped lead the Dodgers to the National League pennant with a .297 batting average and a league-best 29 stolen bases. He also won the Rookie of the Year — an award now named for him in both the National and American leagues.

“He was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides,” Martin Luther King Jr. said in 1962, following Robinson’s induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

David McMahon, co-writer and co-director of the PBS documentary “Jackie Robinson,” said in an email that Robinson “was truly on his own” on his opening day. “I don’t think he had friends in the mainstream press or on the team. No enemies, but no open support.”

“Now we think of it as a watershed moment — and it absolutely is — but the nation did not go on pause that day to see how Robinson’s debut played out,” he added. “The game did not sell out. There were 6,000 empty seats. I don’t think the coverage in the white press was underwhelming by design. These were different times.”