By Curtis Bunn

Grassroots organizers working to turn out Black voters on behalf of Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock in next month’s runoff election expected to encounter an exhausted electorate as voters prepare to head to the polls for the second time in as many months. They underscore the importance of educating Black voters about the significance of the Dec. 6 runoff between Warnock and Republican contender Herschel Walker.

Yet voting rights organizations supporting Warnock say Black voters they’ve spoken with remain energized because expanding Democrats’ majority in the Senate even by a single seat would have a significant impact. It would allow the party to combat occasional outliers like Sen. Joe Manchin, the West Virginia Democrat with a history of voting against his party.“It is critical we get the largest margin possible, and 51 is determinatively better than 50,” said Rahna Epting, the executive director of MoveOn, a progressive grassroots organization. “It means Republicans can’t block as much of our agenda as they could otherwise.”

In last week’s election, Warnock got 90% of the Black vote, compared with Walker’s 8%, according to the NBC News Exit Poll. In the 2020 general election against Kelly Loeffler, the white Republican incumbent, Warnock got 92% of the Black vote and 93% in the subsequent runoff, NBC News exit polls said. The show of Black support for Warnock in this year’s midterms, combined with African Americans’ role in turning the traditionally red state blue in 2020, has helped keep many Democratic Black voters engaged in the contest.

Epting’s group began working the day after the runoff was declared, “moving on all cylinders,” she said, to encourage Black voters to come out to support Warnock next month. That meant calling voters to remind them of the urgency of the runoff, a consistent email campaign with a similar message and door-to-door canvassing.

“We have to let people know we’re in a runoff and what’s at stake between electing Warnock or Walker,” Epting said. “If we do our job to educate folks about what’s at stake, that there is a runoff election and this is the day by which you need to vote and here’s how you do it … I think we can win.”

Lloyd Ramsey, an Atlanta voter who works in retail sales, agreed, saying voters “might be tired of having to go to the polls” but “aren’t too tired.”

“No doubt, we know we can influence elections here in Georgia, which was something we couldn’t say before 2020,” he said. “We’ve always wanted this power or whatever you want to call it. Now that we have it, we won’t misuse it by not voting in the runoff. That’s not happening — tired or not.”

Warnock is counting on Black people to flood the polls as they did in 2020 and 2021, when their record turnout was decisive for Joe Biden to win the presidency and Warnock and Jon Ossoff to win Senate seats.

“I’m concerned that people are tired, but I’m not convinced that will translate into lower voter turnout of Black people,” Epting said. “We have long been tired in this country from the problems and how we’ve been marginalized and how we’ve been treated. I think voter fatigue is real, but I think it’s fatigue across the globe around the challenges that we are all facing at this point. … But Black people have shown up for democracy for generations, and I believe that we will show up again in Georgia.”

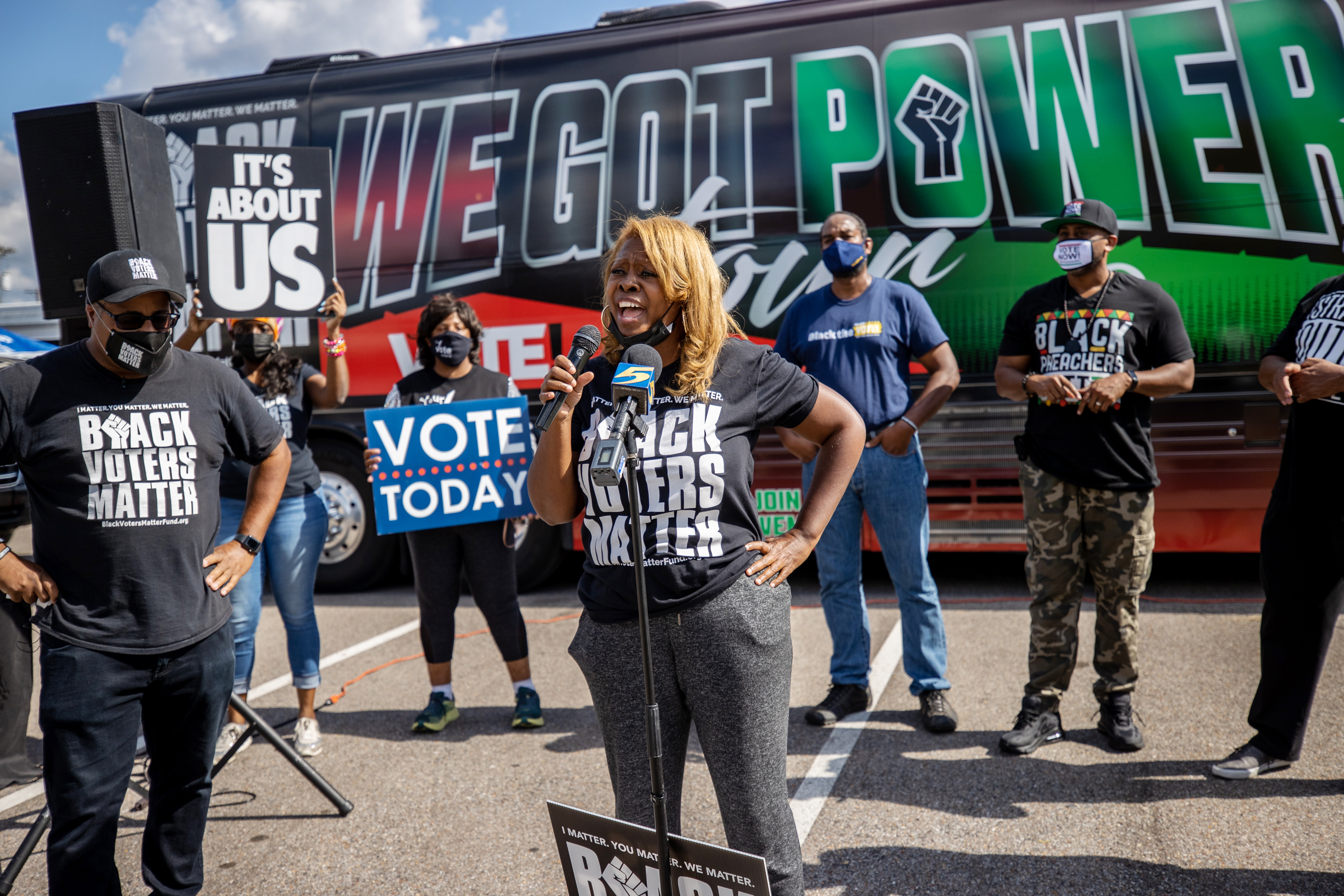

To ensure they will, grassroots organizations like Black Voters Matter have continued their work, attacking the runoff full bore.

“They say that the average voter needs to get at least five contacts in order to be reminded to go vote,” said Cliff Albright, a co-founder of Black Voters Matter. “So we’re doing text messages. We’re doing social media messaging. We’re doing radio ads. We’re doing door to door. We’re doing phone calls. We’re doing digital advertising on streaming services. … You name the kind of outreach, and we’re doing it.”

Georgia native Hillary Holley, the executive director of Care in Action, another voting and advocacy group, said she has felt a surge of energy from Black voters over the last two years.

“This is a story of resiliency,” Holley said. “My family and friends, they’ll say: ‘Oh my gosh. We have to vote again?’ But then they’re like: ‘OK. All right. When is it? What do I need to do?’ We are pivoting again, and people are ready.”

She said her organization was ready for a runoff before the general election. “We know that we live in Jim Crow still,” Holley said. “We started planning for the runoff weeks ago. And those plans are in motion. They’re literally knocking on doors.”

While advocacy groups in support of Warnock are finding ways to keep the Black voter momentum going ahead of the runoff, Walker’s team is also strategizing, hoping for more campaign funds from the GOP. NBC News reported this week that Walker’s campaign had taken note of fundraising by other Republicans, including former President Donald Trump’s Save America PAC, off his runoff but giving Walker only a small part of the proceeds.

“We need everyone focused on winning the Georgia Senate race, and deceptive fundraising tactics by teams that just won their races are siphoning money away from Georgia,” Walker campaign manager Scott Paradise said. “This is the last fight of 2022, and every dollar will help.”

Fundraising efforts and getting out the vote are major priorities for both candidates, but Holley, like other leaders of advocacy groups looking to rally Black voters, said there is also a need to counter voter suppression. Some insist that there are elements of it in a bill called SB 202, also known as the Election Integrity Act of 2021, which was passed last year in Georgia. The new voter guidelines mandate a four-week turnaround for runoffs, only one week of early voting and no opportunity to register and cast ballots before runoffs. To that end, Warnock’s campaign is suing the state because the new restrictions allow for only one Saturday to vote before Dec. 6.

“All the elements we’re talking about impact mostly Black voters,” Albright said. “They carved out this voter suppression bill in Georgia with surgical precision. Black and brown people disproportionately vote more on the weekends and early. This is all a response to the massive turnout we saw in the runoff in 2020 after eight weeks. But it’s also why what we do is so important.”

Albright said what he sees as voter suppression attempts have been vast but unsuccessful, as evidenced by the general election turnout. Instead, he believes the attempts “could be galvanizing Black voters.”

“People like to say: ‘Oh, you had such a big turnout in Georgia. I guess there wasn’t voter suppression,’” Albright said. “No, that’s not what it means. It just means that we’ve been able to organize and that Black voters have responded in a way where we’re resolute about not being blocked from voting. And tired or not, Black voters will come out for the runoff.”