By Kate Martin

The hospital where Sharita Godwin works in central North Carolina doesn’t have any Black nurses trained in administering forensic exams to sexual assault victims.

She’s aiming to become the first one.

Last week, Godwin joined seven other nurses from across the region at Fayetteville State University, as part of the historically Black school’s first class for aspiring sexual assault nurse examiners. The program, which took place over a couple of multiday sessions this fall, trained nurses to treat patients in crisis, including collecting forensic evidence for law enforcement and preventing sexually transmitted infections or pregnancy.

Godwin, an emergency room nurse at Betsy Johnson Hospital in Dunn, North Carolina, for the past eight years, said she wanted to become certified in sexual assault exams as a way of supporting some of the most vulnerable patients the hospital treats.

“It makes you feel a little bit more comfortable,” Godwin, 36, said of patients seeing a nurse who looks like them. “The patient might be more willing to open up.”

About 1 in 5 North Carolina residents are Black, according to census records, but nurses trained to treat sexual assault patients are overwhelmingly white, said Jennifer Pierce-Weeks, CEO of the International Association of Forensic Nursing, an industry group focused on training.

The training program at Fayetteville State was the first Pierce-Weeks had heard of at an HBCU, and she hopes to see more efforts to diversify the field of sexual assault nurse examiners.

“What Fayetteville State is doing is critically important and a huge step,” Pierce-Weeks said, “because I feel like nursing in general is struggling with this.”

A 2020 survey found that 81% of registered nurses in the U.S. were white and just 6.7% were Black, according to the Journal of Nursing Regulation.

Dr. Sheila Cannon, associate dean of the school of nursing at Fayetteville State, organized the recent training with funding from the state Legislature.

That $1.5 million appropriation for Fayetteville State came on the heels of a news report last year that showed few sexual assault nurse examiners worked in rural North Carolina hospitals, which meant some patients had to travel hours from home or wait days for care.

The reporting spurred a flurry of action at the state and federal level to pay for training and supporting sexual assault nurse examiners. Congress approved $30 million per year for the next eight years for this work, and Cannon hopes to secure some of the federal funds to expand the program.

It was a struggle to get this program to Fayetteville State University at all. Cannon had tried to secure a federal grant, but lost out to schools with more resources or their own hospital, like the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Training is typically offered at a few hospitals or universities and can cost hundreds of dollars.

Cannon, who is Black, said that before she worked at Fayetteville State she was a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner, and some of her psychotherapy patients were victims of sexual abuse or molestation.

“I know the impact of trauma is lifelong,” Cannon said. “You sustain such a level of trauma that you really need supportive intervention from the very beginning. You need someone there advocating for you, someone giving you compassionate care.”

Last week’s hands-on course, which was free thanks to the legislature’s funding, aimed to help the nurses feel more comfortable treating sexual assault patients.

On the first day of clinical training, the students practiced what they had learned in the classroom by doing exams on forensic teaching associates, who served as both models and teachers as the nurses asked them for consent to collect evidence from their bodies, look for injuries and practice speculum insertions. An exam can take up to six hours — and perhaps double that if a nurse isn’t trained and is reading the instructions of a rape kit for the first time.

Although Godwin knew it was an exercise, she was still nervous to get started.

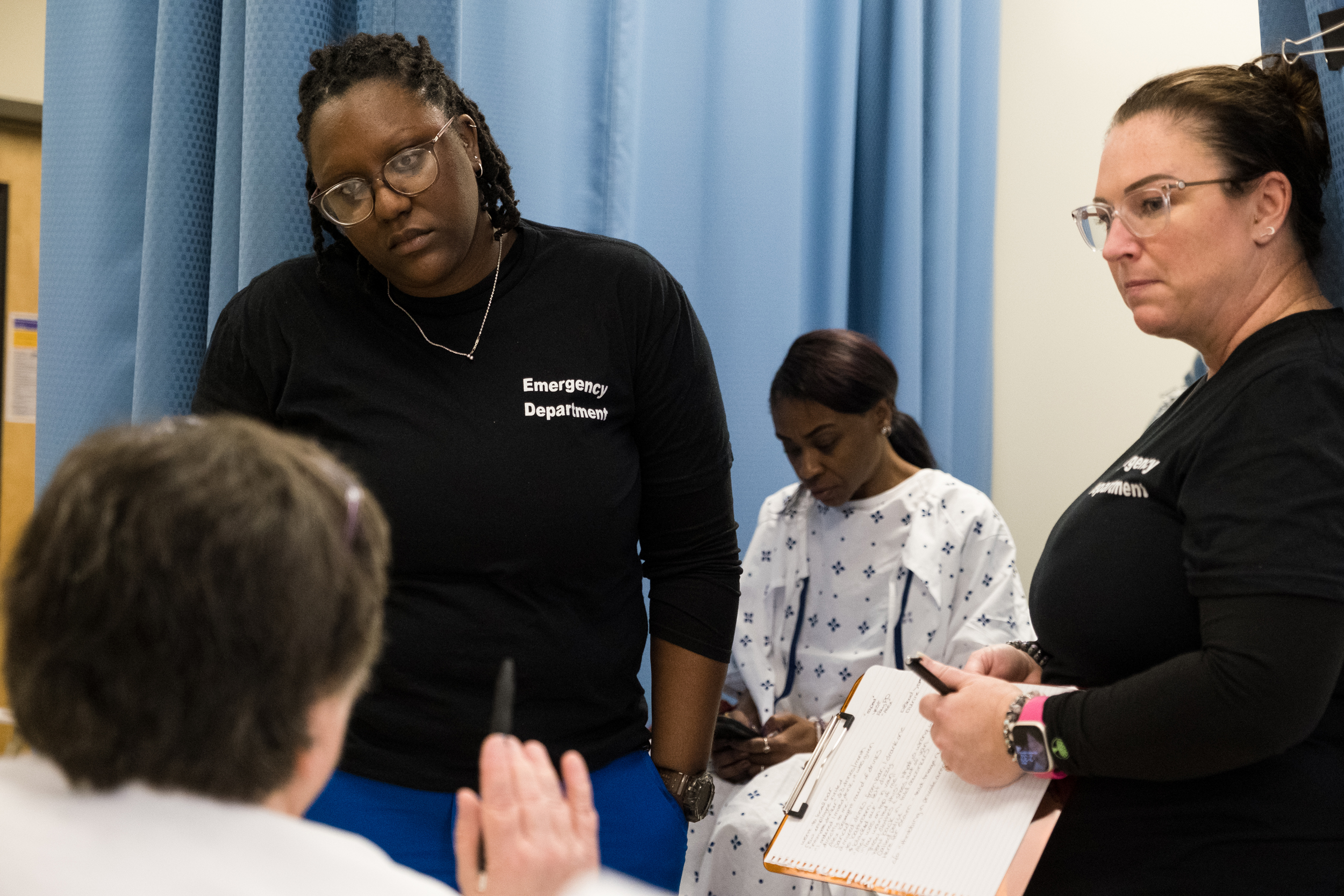

“Are we doing this now?” she whispered to Beth Andrews-Arce, her co-worker at Betsy Johnson Hospital, as they stood on one side of a thin curtain separating them from a forensic teaching associate who was acting the part of an assault victim waiting for care.

Andrews-Arce nodded and picked up a clipboard. Godwin pushed the curtain aside, sat down on a nearby stool and introduced herself to the woman. She tried to get a sense of what happened to her. The answers to those questions would help guide the exam toward DNA that may have been left behind by an attacker. Godwin paused occasionally to ask questions of her instructor.

Afterward, Godwin said the training helped her have more confidence in doing the exams.

“I want to learn my script of how I move through things so I can be more efficient and the patient can feel more comfortable and confident in what I’m doing,” Godwin said.

One of the forensic teaching associates was Ava Davis, a Black transgender woman from Atlanta. She said she does this work because she wants sexual assault exams for trans people to be “less nerve-wracking.”

“So many trans victims are afraid to report,” she said.

After last week’s training concluded, the students headed back to their hospitals. Some will try to secure a quiet space away from the busy emergency room for sexual assault victims to wait. They will also stock the supplies they will need for exams, and connect with rape crisis centers and law enforcement in their area to let them know someone at their hospital is trained to help sexual assault patients.

Each student will be assigned an experienced sexual assault nurse examiner as a mentor. The program will also pay for each student to sit for an exam within about two years for an official certification through the International Association of Forensic Nurses. Before they can earn that credential, they must perform exams on two sexual assault patients.

Cannon plans to hold three more training sessions next year and said more than two dozen people have signed up for one in the spring. By the fall, she expects to have trained about 60 to 80 nurses, with priority given to students from North Carolina, especially for the clinical portion. She hopes Fayetteville State can become a regional hub for this training. With more funding, she said the school could offer refresher courses for nurses whose skills have lapsed.

The work of examining sexual assault patients can be isolating, and many nurses let their credentials expire because of burnout, Cannon said. She hopes that having more nurses trained will allow them to share the work and stay in the profession longer.

“You know why it’s emotionally draining? It’s only one person serving one hospital,” Cannon said. “If you have more supply, and you have a person stationed in every ER — more than one — it’s not going to be too taxing on that person.”