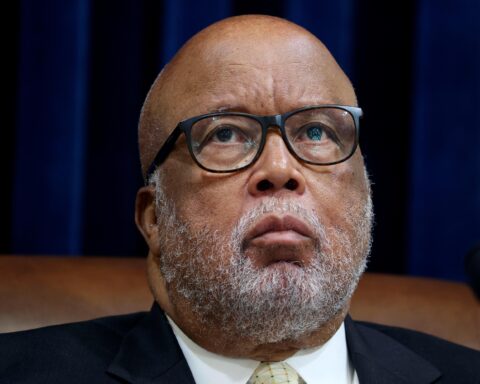

The House sergeant at arms, who was the head of the D.C. National Guard during the attack on the Capitol, told the Jan. 6 committee that the law enforcement response would have looked much different had the rioters been Black Americans.

“I’m African American. Child of the sixties. I think it would have been a vastly different response if those were African Americans trying to breach the Capitol,” William J. Walker told congressional investigators, in an interview transcript released Tuesday. “As a career law enforcement officer, part-time soldier, last five years full but, but a law enforcement officer my entire career, the law enforcement response would have been different.”

His testimony echoed the observations of many Americans, including President Joe Biden, who noted the stark difference in the law enforcement response to protests in Washington following the May 2020 murder of George Floyd and the lax security at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

William J. Walker, the head of the D.C. National Guard during the insurrection, also indicated he thought more people in the crowd would have died if the mob had been largely Black instead of overwhelmingly white.

“You know, as a law enforcement officer, there were — I saw enough to where I would have probably been using deadly force,” he said. “I think it would have been more bloodshed if the composition would have been different.”

Walker, a former Drug Enforcement Administration official who became the House sergeant at arms in April 2021, also described his personal experiences with discriminatory law enforcement stops, and discussed having “the talk” with his five children and his granddaughter about surviving police encounters as a Black American.

“You’re looking at somebody who would get stopped by the police for driving a high-value government vehicle. No other reason,” Walker said.

The D.C. National Guard was not authorized to assist at the Capitol on Jan. 6 until after a delay of 3 hours and 19 minutes that the House committee’s report pins on a “likely miscommunication between members of the civilian leadership in the Department of Defense.”

Walker told investigators that it was clear to him beforehand that Jan. 6 was going to be a “big deal” just from being aware of what was happening in the world.

“I’m an intelligence officer … to me, the intelligence was there that this was going to be a big deal,” he said, citing the civil unrest in November and December when Trump supporters came to Washington.

“You don’t need intelligence. I mean, everybody knew that people were directed to come there by the president. November was a run-up, December was practice, and January 6th was executed,” Walker said.

“I personally, William Joseph Walker, not General Walker, thought that it was just vastly different,” he said, comparing the unrest of summer 2020 to the unrest after the election. “National Guard is not called in December. National Guard is not called in November. And I watched on television the difference between people coming to the Capitol in November. And if you watch the film, and if these same groups came back in December, better prepare. Better prepare.”

As NBC News first reported last month, the Jan. 6 committee made a decision to focus its final report on former President Donald Trump, and not as much on the law enforcement and intelligence failures and other issues that committee staffers investigated. Part of the panel’s investigation into intelligence failures was ultimately relegated to an appendix, though the report did note that “Federal and local law enforcement authorities were in possession of multiple streams of intelligence predicting violence directed at the Capitol prior to January 6th.”

A spokesman for Jan. 6 panel member Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., told The Washington Post last month that committee staffers had “submitted subpar material for the report that reflects long-held liberal biases about federal law enforcement” and that she would not “sign onto any ‘narrative’ that suggests Republicans are inherently racist or smears men and women in law enforcement.”

Still, the testimony of Walker — a highly decorated commanding general and a long-serving DEA special agent who rose to top leadership positions at the agency before becoming the first Black House sergeant at arms — underscores some of the systemic issues that went unaddressed in the committee’s final report.