By Sara Weissman

Some students and faculty members at historically Black Atlanta colleges and universities are speaking out against plans to build an 85-acre, $90 million police training facility nearby in forested land owned by the city.

The Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, nicknamed “Cop City” by its critics, was approved by the Atlanta Council in fall 2021. The complex is expected to include shooting ranges, a mock city for police training and a K-9 unit kennel, among other amenities, and would be a little less than 10 miles from the Atlanta University Center, which is home to four HBCUs.

The project has been the source of heated opposition for over a year from environmental activists and residents who believe the increased police presence may lead to potential police brutality. Some opponents also see the move as a capitulation to residents of Buckhead, a wealthier and predominantly white neighborhood in Atlanta, where some want to secede from the city because of its crime rates.

Atlanta mayor Andre Dickens and DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond recently announced that they reached an agreement to move forward with the plans and provided details about environmental protections and community engagement efforts.

“Our training includes vital areas like de-escalation training techniques, mental health, community-oriented policing, crisis intervention training, as well as civil rights history, education,” Dickens said at a City Hall press conference. “This training needs space, and that’s exactly what this training center is going to offer.”

Opponents say military-style police training fosters an attitude that police are at war with the people they’re supposed to be protecting. Tensions and organizing around the issue have escalated, with no signs of abating, since the Jan. 18 killing of Manuel Terán, who was part of a group of environmental activists occupying the forest area in protest. Terán was shot more than a dozen times by law enforcement officials who were clearing protesters from the future building site, The Atlanta Constitution-Journal reported. Police alleged Terán shot and injured a state trooper, and multiple officers returned fire.

Students and scholars in the Atlanta University Center Consortium (AUCC)—a coalition of Atlanta HBCUs including Morehouse College, Clark Atlanta University and Spelman College—are among those fighting the plans. Their activism on the issue this month caught the attention of the mayor, who attended a reportedly tense meeting at Morehouse last week, and discussions continue to roil AUC campuses.

An Impassioned Protest

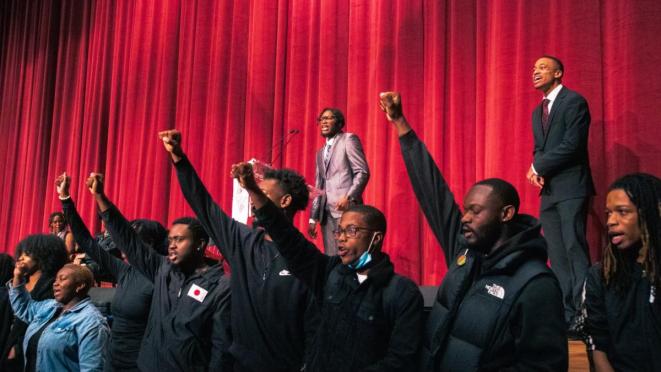

Student activists vocally brought attention to “Cop City” at a weekly speakers’ forum at Morehouse College on Feb. 2. A group of students from Morehouse and Spelman gathered in front of the stage in protest, and some denounced the planned facility in fiery speeches.

Students also pushed back on what they perceived as a tone-deaf joint statement made by Morehouse president David Thomas, the campus police chief, and the Student Government Association president, grieving the death of Tyre Nichols, an unarmed Black man killed by police in Memphis, Tenn., and calling for peaceful protest. The same statement said the SGA president had met with the mayor and the Atlanta Police Department chief to discuss the upcoming policing facility and “confirmed both leaders’ commitment to improved policing practices and relationships with the Black community.”

Daxton Pettus, a sophomore at Morehouse who grew up in nearby DeKalb County and spoke at the forum, said the statement seemed hypocritical for commemorating Nichols while also “giving support to a system that has harmed us as Black people and that harmed Tyre Nichols himself.”

“The seven police officers who engaged in the death of Tyre Nichols were trained,” he said. “We’ve been training police officers more and more, adding more training, but we still continue to see Black people murdered on television.”

The students made several demands, including that Thomas denounce the training center as a board member of the Atlanta Committee for Progress, a group of business, university and civic leaders that advise the mayor. The committee backed the creation of the training facility. Spelman College’s president, Helene Gayle, is also on the board.

Rumors have swirled on social media that Morehouse and Spelman, alongside other universities, financially contributed to the project. Gayle released a statement on Friday saying those claims are false.

The Atlanta Committee for Progress is “not providing financial support for this facility,” she said in the statement. “As such, Spelman is not directly or indirectly providing financial support.”

A statement from Spelman to Inside Higher Ed praised students and promised to support them as they “address the key social issues of our times,” such as police brutality. “We also recognize the important responsibility that the City has for maintaining public safety and the role that training can play in making needed improvements.”

Members of the Spelman student chapter of the National Action Network, a national civil rights organization, gathered over the weekend to draft a letter to Gayle, calling on her to denounce the facility.

Adrian Sean, a junior at Spelman, said it feels wrong to see so many resources go to Atlanta police given their track record. She noted that Atlanta officers killed Rayshard Brooks, a Black man, and forcibly removed a Morehouse student and a Spelman student from a car and Tased them in 2020. She doesn’t believe enough reforms have been made since these incidents to merit a state-of-the-art training facility.

She noted that many students are registered to vote in Atlanta and that more students might remain in the city after they graduate if they felt residents were listened to and their needs were better met.

”We, as well as the residents of the city of Atlanta, need to be taken seriously,” she said. “We’ve said it time and time again. We do not want Cop City.”

Picking Up Momentum

Scholars at Morehouse have also joined the fray. At least 51 Morehouse faculty members signed an open letter condemning the project and calling on “civic leaders and fellow educators” to do the same.

Andrew Douglas, a political science professor and chair of the Morehouse Faculty Council, said instructors were inspired to speak out after seeing the activism displayed by their students.

The issue has been divisive on campus and in the community at large, he said. Some colleagues see the training center as a tool to better protect residents, and students, from crime.

But “if we’re ever going to do anything to get at the root causes of crime, and the sorts of hopelessness and destitution that may lead people to feel like they have no choice but to engage in what we deem criminal behavior, we’ve really got to work on some of those underlying systemic issues,” Douglas said. He believes “throwing more police, even … better-trained police, at those issues” isn’t a fix.

He’s disappointed by the lack of a unified response from AUC campuses, though he recognizes administrators often “have to take a more conservative and cautious approach.”

“I think the AUC schools as a bloc have a tremendous amount of power that, if they were to take a position on this, that would garner a lot of attention,” he said.

Stephane Dunn, chair of the cinema, television and emerging media department at Morehouse, believes universities, and HBCUs in particular, have a critical role to play in the local protest movement.

Dunn, who’s also an English professor, noted that sometimes universities can be in an academic “bubble” and removed from the problems affecting their surrounding communities. But AUC campuses are different, she said. “How can we be quiet or act like nothing is going on when we have been in the streets, we have been writing about what’s happening in terms of police brutality, for years?”

Kamau Franklin, founder of Community Movement Builders, a Black community-organizing group that also has been protesting “Cop City,” said the activism by students, and the support of their professors, counteracts a pervasive idea that the protesters are “outsiders” making trouble. He noted Georgia State and Georgia Tech students held protest rallies against the project as well.

“These are students who were invited into Atlanta, some who are from Atlanta or the surrounding areas, who are here protesting and saying they don’t want a militarized police facility in their backyard,” he said.

Calvin Bell, a Morehouse junior who also spoke at the speakers’ forum, noted that AUC student organizing on this issue could create inroads for working with the surrounding community on other issues. For example, the area around the AUC is now a food desert after a Walmart temporarily closed, hurting students and local residents, he said.

”How can we work with the local community to ensure we all have the services, the social programs we need to lead successful lives?” he said.

A ‘Tense Encounter’

Mayor Dickens met with Morehouse students on campus on Feb. 7 in response to the protest. The meeting was only intended for AUC students and employees, but videos of the gathering were posted on social media, bringing more attention to students’ concerns.

“It was a very, very tense encounter,” said Douglas, who gave a short speech at the meeting as a faculty representative. Pettus spoke as well, as did the mayor and other officials. Dickens also answered questions at the event, which lasted several hours. Students asked about the environmental impact of the project, how the city planned to mitigate police brutality and why the training center is being prioritized over other city needs.

At one point, Dickens responded to hecklers in the audience who questioned his commitment to the community.

“I ain’t never been a sellout,” he said. “You’ve got the wrong résumé that you’re looking at. I know you like to yell … and shout out things just to be heard. You’ve been heard.”

Douglas gave Dickens credit for spending hours answering student questions, “but it was very clear that the mayor was not going to change his view on things,” he said.

Thomas said during the meeting that he personally believes Atlanta needs the new facility, though he emphasized that Morehouse, as an institution, has taken no such stance.

But Pettus said, “The absence of a stance is a stance in itself.” He described the event as unproductive and more about marketing the center than responding to student concerns.

Bell said at the very least “a lot of students were able to get what they had off their chest, in terms of their emotions, in terms of their feelings around this issue.”

Franklin, of Community Movement Builders, is hopeful that students can make a difference by possibly having a “ripple effect” and drawing solidarity from other students across the country. He sees their activism as “potentially a turning point” in the wider protest movement.

Pettus said he and other students plan to continue to raise awareness about “Cop “City” on their campuses. For example, he and others went to Spelman’s on-campus market on Friday and set up a table to engage students on the topic. A group chat they created for AUC students interested in learning more and keeping up with local protests has reached about 400 members in the last couple weeks.

“The numbers are always growing,” he said.