By Jasmine Wright

It was a rare show of emotion for the typically stoic barrier-breaking leader, often reticent to talk about her own plight as a Black woman in America. But at a makeshift podium in front of the cannons that stretch along the ocean, Harris’ voice broke as she talked, delivering at times off-the-cuff remarks to describe what she saw.

“Being here was immensely powerful,” Harris said at the castle, a relic of transatlantic cruelty. “The crimes that were done here. The blood that was shed here.”

“The horror of what happened here must always be remembered. It cannot be denied. It must be taught; history must be learned.”

Cape Coast Castle has become a feature of Western leaders’ visits to West Africa, a way to pay penance for the past sins of the nations that shipped and sold African bodies and chart an optimistic future for their descendants both still on the continent and across the globe.

Harris’ visit had echoes of those by former President Barack Obama, who visited the landmark with his family in 2009. And his mark on Cape Coast Castle, as the first president have a direct bloodline to the continent, was evident when Harris stared upon a plaque unveiled by Obama on the wall to the left of the male dungeon door.

But absent from her remarks was her personal connection as a Black American and woman in power. A daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants, Harris has often described her decision to become a prosecutor, her career before entering politics, to right injustices she witnessed growing up in a predominately Black neighborhood in Oakland, California.

At the castle Tuesday, Harris only talked broadly about Blackness and the progress that must be made for equality.

“We must then be guided by what we know also to be the history of those who survived in the Americas, in the Caribbean, those who proudly declare themselves to be the Diaspora,” Harris said.

“All these stories must be told in a way that we take from this place, the pain we all feel the anguish that reeks from this place. And we then carry the knowledge that we have made gained here toward the work that we do in lifting up all people. In recognizing the struggles of all people, of fighting for as the walls of this place talk about, justice and freedom for all people, human rights for all people.”

The plight for Black Americans that Harris and the wider Biden administration must confront has worsened in many ways since the last Black White House principal – Obama – took office nearly 15 years ago. That’s despite the increased focus on race and racial inequality in the US since the pandemic and uprisings to counter police violence of 2020.

Obama told CNN during a 2009 interview at Cape Coast that slavery, a terrible part of the US history, should be taught to connect past transgressions to current events. Harris repeated that belief on Tuesday as Black history studieshave come under fire in conservative circles in America, a move critics have called whitewashing history to distort the reality of slavery and its impact on America.

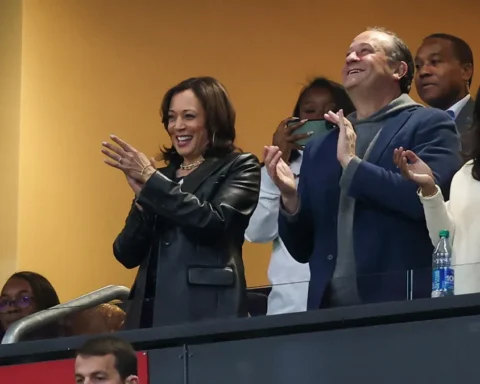

Throughout the tour, Harris and her husband Doug Emhoff frequently shook their heads in dismay at the inhumane way slaves were treated in the very place they walked. At one point, Harris broke off on her own to gaze across the water with her hand under her chin and appeared to wipe her eyes. The second gentleman often looked just as distressed beside her. In her remarks Tuesday, she described what she learned.

“They were kidnapped from their home. They were transported hundreds of miles from there not really sure where they went. And they came to this place of horror,” she said. “Some to die, many to starve and be tortured. Women to be raped before they were then forcibly taken on a journey thousands of miles from their home to be sold by so-called merchants and taken to the Americas to the Caribbean to be an enslaved people.”

Before the vice president toured the slave outpost grounds, she and her husband received a welcome ceremony from Cape Coast Chief Osabarima Kwesi and other officials.

There, he warned the vice president of what she would soon see.

“When you go there and you carefully look around, you will ask yourself so many questions. Why should anybody treat anybody the way our ancestors were treated. And this is a lot of thought,” he said to Harris. “But we are not in those days now. Now we are here to mend and build to hold each other’s hands for a better future.”

A vision for the future is the impetus of Harris’ diplomatic mission to the continent. She became the most senior Biden officials to travel to Africa this year as they attempt to reassert the US’ presence and reset relationships – all while China’s foothold on investments serves as a critical backdrop to her historic trip.

A reflection of the returns on diplomacy the US will find itself beholden to because of their acceleration push for partnership, Kwesi asked Harris to coordinate a trip for Cape Coast officials to the US to solidify their conversations and help build a slavery museum for the community. In response, Harris appointed the US ambassador to Ghana to act as a liaison between the White House and Cape Coast.

And as a show of community and a budding relationship with America’s highest-profile Black leader, Harris and Emhoff also were gifted traditional Kente fabric, Harris’ was draped on her shoulder and Emhoff’s was wrapped around his body.

Before departing the slave castle, Harris returned to a similar theme throughout her time in office: the fight for justice.

“The descendants of the people who walk through that door were strong people, proud people, people have of deep faith. People who love their families, their traditions, their culture, and carried that innate being with them through all of these periods,” she said. “Went on to fight for civil rights, fight for justice in the United States of America and around the world. And all of us, regardless of your background, have benefited from their struggle and their fight for freedom and for justice.”