By Sara Weissman

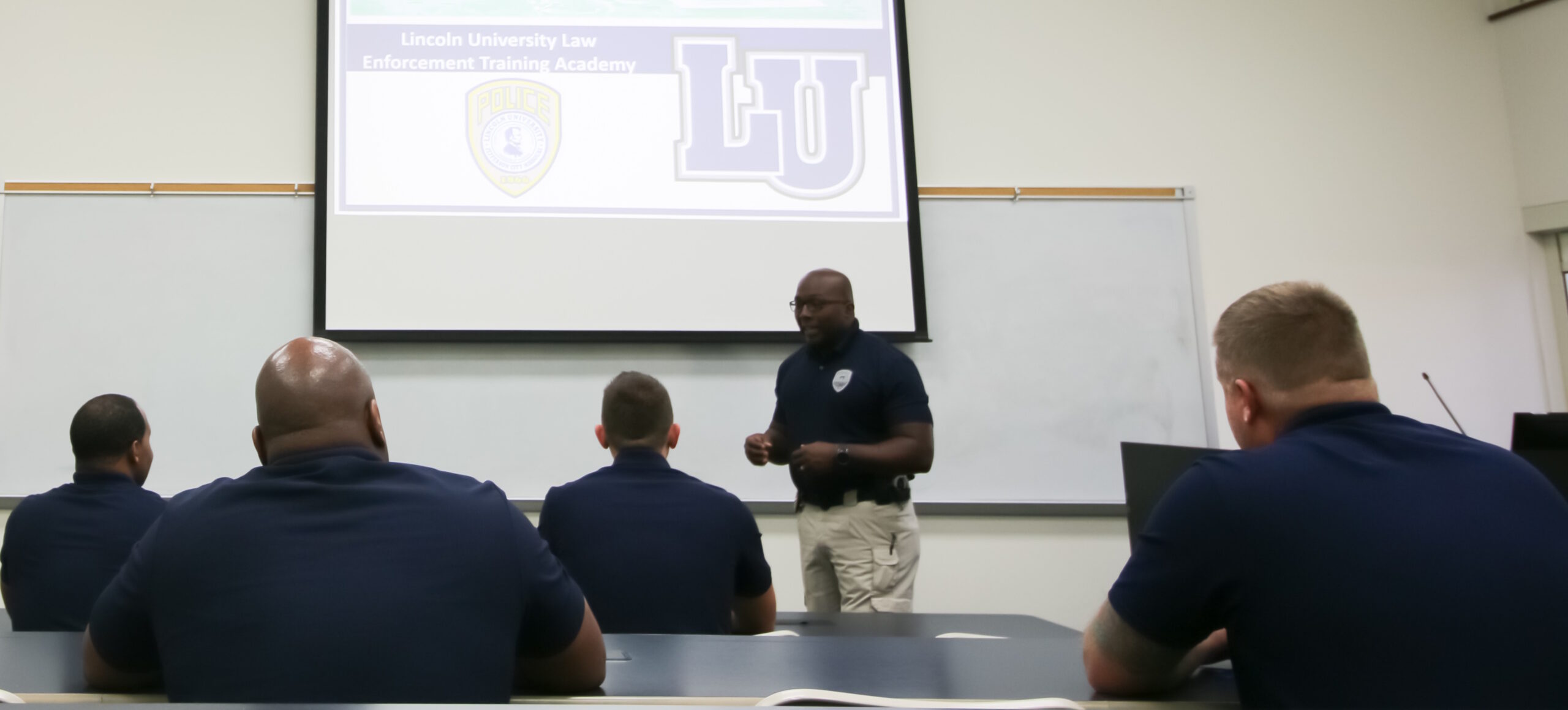

Students at the Lincoln University Law Enforcement Training Academy gathered on Wednesday for a class discussion about a policing incident in nearby Columbia, Mo. Two officers are under investigation after a video surfaced showing one of them beating a man pinned to the ground.

The police officers and the victim all appear to be white. The group also had a class discussion after the death of Tyre Nichols, a Black man killed by police officers.

“We play that, and we talk about it,” said Lincoln University Police Department chief Gary Hill. “What do we think about this? What did we learn about use of force, and how does that apply to what [the officer is] doing? We have example after example.”

Those conversations can be hard, Hill said. But at the same time, there’s a sense of security that comes with being in a “Black space, where people of color feel comfortable in their environment and pursue a career in a place that’s going to be inclusive.”

The academy, launched in 2021, is the first and only police academy at a historically Black university. But Hill said several HBCUs have expressed interest in creating similar officer-certification programs, and he’s repeatedly been contacted by police departments looking to recruit his students and build partnerships.

Interest from police departments in hiring HBCU graduates is “really, really growing,” he said. “You’re starting to see it all around the nation, not just here.”

As police departments seek to diversify, particularly after the national racial reckoning in 2020, some are turning to historically Black colleges and universities, like Lincoln, as a source of new hires and launching new efforts to engage HBCU students and fill their ranks.

The Cleveland Department of Public Safety, for example, sent recruiters to a series of career-related events at HBCUs in a push to attract more diverse officers in a city that’s about 47 percent Black and 12 percent Hispanic, The Marshall Project reported. The Baltimore Police Department also piloted a 10-week internship for HBCU students last summer in partnership with its local HBCUs, Morgan State University and Coppin State University, and plans to offer the program again this year. The North Carolina Department of Public Safety similarly offers a semester-long internship program for students at HBCUs or other minority-serving institutions.

Many police departments have long been less diverse than the communities around them. Out of 467 local police departments with at least 100 officers, more than two-thirds became whiter than the communities they served between 2007 and 2016, according to a 2020 New York Times analysis of U.S. Department of Justice data. A 2021 analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by ABC News similarly found that white officers were overrepresented relative to their surrounding populations in 99 out of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S.

Cleveland police chief Dornat “Wayne” Drummond said he wants to “build a lasting relationship” with local HBCUs in Ohio, such as Wilberforce University and Central State University, that creates a pipeline to Cleveland law enforcement so officers better reflect the city’s population.

“We’re trying our very best to get the most qualified persons to become police officers,” he said. “It’s also very important that we have a police force that’s representative of the communities that they’re serving.”

Tulsa chief of police Wendell Franklin, a graduate of Langston University, an HBCU in Oklahoma, said recruiting police, especially Black officers, has become more difficult in recent years as law enforcement came under heightened public scrutiny. He noted that the Tulsa Police Department has long looked to HBCUs as a valuable source of talent, particularly nearby institutions such as Langston and the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, but those efforts feel especially important at time when it’s so challenging to make hires.

“Every law enforcement entity is recruiting from the same recruiting pool, and … there’s less people in that pool, because there’s less people willing to go into the profession,” he said. He’s concerned that dynamic creates a cycle where police departments struggle to attract diverse officers who are passionate about improving how communities of color are policed. Currently, about 72 percent of the 803 sworn officers in the Tulsa department are white, 7 percent are Black, 6 percent are Hispanic and 10 percent are Native American.

“We are calling out and saying, ‘Hey, look—we recognize that there’s a need for us to be better, and we’re always striving to be better, and we would rather a person be a part of the solution …’” he said. As Americans “ask for change, as there’s this need for change, we have to get the right people in here. Otherwise, the only people doing this job are going to be the people who shouldn’t be doing this job.”

He also believes it generally pays off to hire highly educated officers, which is why his department requires officers to have bachelor’s degrees. Some research indicates police with a college degree are less likely to use force and garner fewer citizen complaints on average.

“We think we get a better critical thinker, a person who’s had some life experience,” Franklin said. “We want them in these roles.”

Leslie Parker Blyther, equity office director at the Baltimore Police Department, said police initiatives to engage HBCU students are still “scattered” and not as widespread as they could be, but she believes they have a lot of potential. Her department hired two of the eight students who participated in its paid internship program last year.

Blyther said initially some of the interns were “very uncomfortable,” and one was reluctant to join the internship program at all, because of negative associations with policing. But the program involved police leaders having frank, open conversations with students about the history of “unconstitutional policing of African American people and other marginalized people” and actively soliciting their feedback on day-to-day operations and how to further improve relationships between police and Black communities, she said. In that vein, the internship culminated with students presenting capstone projects in which they detailed aspects of the department’s policies or operations that they thought needed improvement.

Police department officials and local HBCU leaders came together around the idea that Black students can “play a significant part in police reform,” Blyther said.

Not everyone is enamored with the bridges being built between police departments and HBCUs. Some critics argue diversifying police forces with HBCU graduates is a Band-Aid solution to deeper problems with the policies and tactics employed by police departments.

LaTonya Goldsby, president and co-founder of the Cleveland chapter of Black Lives Matter, said these recruitment efforts at HBCUs give “the illusion that hiring Black officers will improve the relationship between Black communities and law enforcement, and that can’t be further from the truth.”

“Truth is that Black police officers kill Black people, too,” she said. “Once you become a part of that culture, you’re to conform to the way in which that culture operates.” She pointed to the killing of Nichols, a Black man who died after a beating by a group of Black Memphis, Tenn., officers in January.

She believes it’s important to have officers that “come from our community and have that degree of … cultural awareness,” but it can’t be marketed as a wholesale solution. She said she’d like to see more police departments require officers to have a college degree and policy makers focus on the conditions she believes lead to overpolicing in Black communities, including insufficient access to affordable housing, well-paying jobs and higher education.

Drummond agrees that more a diverse police force isn’t a panacea, but “individuals who believe there are inequities in police departments” are the people departments should be employing, he said. HBCUs are one place to find would-be officers who “understand what we’re trying to do, which is to foster really good relationships with our community” and who can “make a difference in the service we’re providing or will provide the community.”

Hill said plans to launch the police academy at Lincoln initially received a significant amount of pushback on the heels of the killing of George Floyd.

But “a lot of students stepped up to the plate and said, ‘I want to be the change,’” he said.