By Scott Tong

The new International African American Museum , which opened last month in Charleston South Carolina, stands at a location that is itself drenched in history.

The museum is on Gadsden’s Wharf, where ships carrying enslaved people from Africa arrived to bring them into bondage in America. Gadsden’s Wharf was one of the nation’s largest trans-Atlantic slave ports, says Tonya Matthews, president of the museum.

Historians estimate nearly half of enslaved Africans who came to America arrived and entered at the port complex in Charleston.

“It was a major point of commerce,” Matthews says. “And a big part of that commerce was enslaved people.”

Matthews calls it hallowed ground, with the museum transforming an entry point of enslavement into a location for education. She points out that the entire museum structure doesn’t actually touch that ground. Instead, it rises up on pillars.

Outdoor space for walkways, gardens, a reflecting pool are beneath the building and on the grounds overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Architect Henry Cobb designed the rectangular, single-story structure to appear to float 13 feet off the ground.

“He decided that his challenge was to design a building for which the ground it stood upon would always be more important than the building itself,” says Matthews. “He decided that therefore the museum would not touch the ground.”

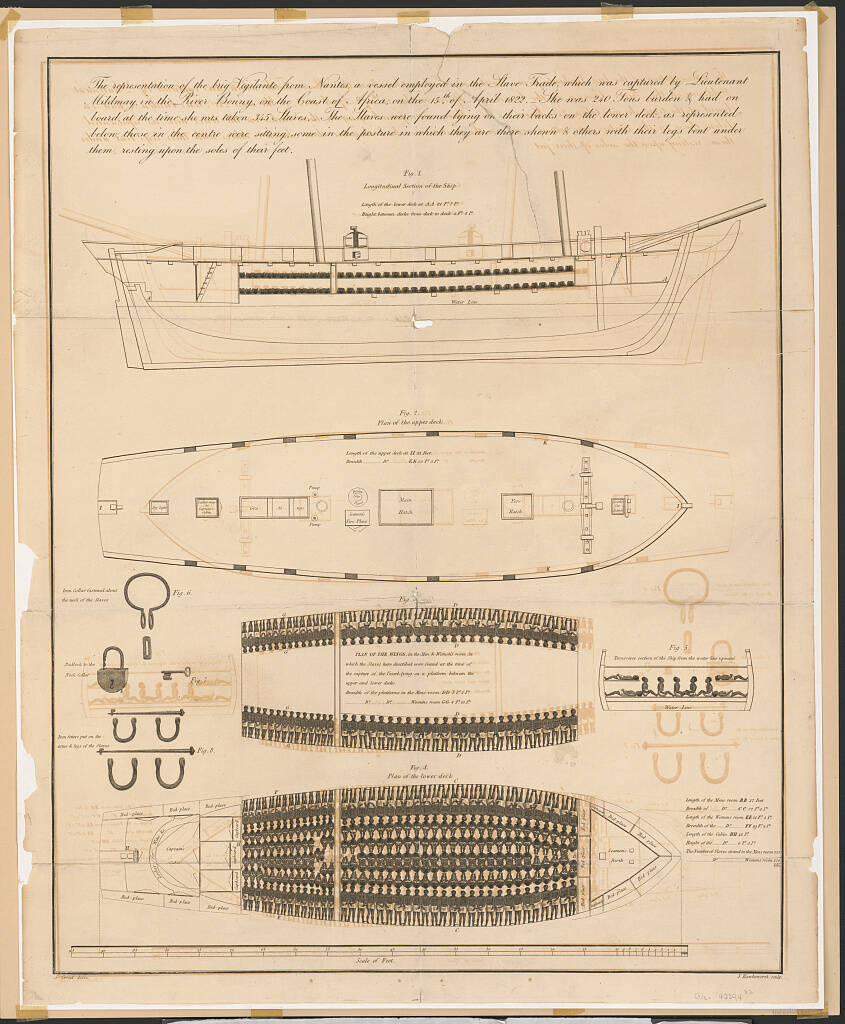

The grounds include a Tide Tribute pool with an art instillation at the bottom. Embedded in the concrete ground is an engraved relief inspired by the Brooks diagrams which illustrate how Africans were shackled and packed into ships.

“It’s a place with all the emotions. As the waters are going down, there are days I am reminded of those that we lost,” says Matthews. “But as the waters are coming up, there are days I am reminded of those who did ultimately rise up out of this space to give rise to everything we are trying to do today.”

The museum includes a Center for Family History where people can investigate their ancestry.

“It was thought that African Americans couldn’t go back very far because of the record keeping, because of the family separation, because of slavery itself,” says Matthews.

Civic leaders, artists, elected officials have been working and contributing for more than two decades to bring the museum to life. And Matthews says the museum strives to bring a rich history fully to life.

“It’s not always trauma, and it’s not white washed to give you a false sense of joy,” she says. “It’s this African American ethic of trauma and joy constantly interwoven, simultaneously inside every story that we tell.”