By Liam Knox

Over the past few weeks, a steady stream of highly selective colleges have reported significant declines in first-time Black student enrollment, a drop most institutions have pinned on the Supreme Court’s 2023 affirmative action ban.

But one college’s challenge is another’s opportunity: Historically Black colleges and universities appear to be benefiting from a windfall of applicants and new students this fall.

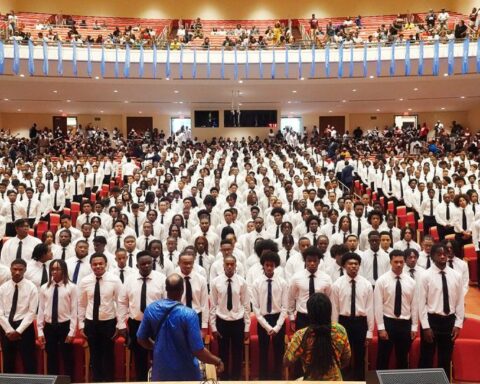

Applications to Hampton University, a private HBCU in Virginia, rose from 13,000 to 17,000 for the Class of 2028. Morehouse College, an all-male institution in Atlanta, had more than 8,000 applications this year, a 34 percent increase from last year’s 6,000, according to data that the college made available to Inside Higher Ed. At Howard University—often called “the “Harvard of HBCUs” for its selectivity and list of notable alumni, including Vice President Kamala Harris—applications rose by 10 percent over the previous cycle, from 33,000 to 36,300.

Initial data for the Class of 2028 suggests that fall enrollments at HBCUs are following suit. First-time enrollment at Alabama State University increased by 12.5 percent, according to a university statement, though that includes first-time graduate students. At Bethune-Cookman University in Florida, first-year enrollment increased from 814 in fall 2023 to 1,150 this year.

Such increases build on a 4 percent overall enrollment boost at HBCUs for the spring semester, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

At Howard, first-year enrollment increased from 2,268 in 2023 to 2,796, according to Tashni-Ann Dubroy, Howard’s executive vice president and chief operating officer. Dubroy told Inside Higher Ed that her institution had been anticipating an increase in applications since last year.

“After the Supreme Court decision, we knew we’d see an uptick in interest from African American students who ordinarily have multiple options, including predominantly white institutions,” she said.

Harry Williams, president of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, a nonprofit that advocates for public HBCUs, said he’s been hearing about enrollment jumps from leaders at almost all of the fund’s 42 member institutions, including those that have yet to make enrollment data public.

“Alabama State, North Carolina A&T, Morgan State—they’re all seeing record numbers. Even smaller schools like Bowie State [in Maryland] are bursting at the seams,” he said. “After [the] affirmative action [ruling], interest in historically Black colleges and universities is at an all-time high.”

‘Value in a Sense of Belonging’

This isn’t the first time HBCUs have seen an enrollment boom. Interest in the universities has been on the rise for nearly a decade, with a notable uptick in 2020, when the murder of George Floyd prompted a national reckoning with systemic racism in higher ed and beyond; President David Thomas said that Morehouse saw a 60 percent jump in applications that year.

Williams said that over the past two years, as the pendulum has swung away from the 2020 reforms and attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion have intensified, interest has only increased.

“Everything that’s been going on politically, from affirmative action to DEI, sends a message to Black students that they don’t belong,” he said. “At an HBCU, you’re never going to have that question, and all of the support, resources and scholarship money being taken away elsewhere are already built into the structure [at HBCUs] … there’s value in a sense of belonging.”

Williams added that the enrollment increase at HBCUs is especially remarkable given the likely impact of last cycle’s botched federal aid form rollout, which disproportionately affected low-income students of color—a population with a substantial representation at most HBCUs.

Thomas said HBCUs should capitalize on the burst in interest, especially from middle-class, millennial Black families, by demonstrating that their degrees can be just as valuable as those from highly selective predominantly white institutions, if not more so.

“I’ve been telling my colleagues, we’ve been elevated by the social and cultural moment,” he said. “Now we need to make our value proposition.”

Too Much of a Good Thing?

The influx of student interest in HBCUs raises an important question: Can the often-underfunded institutions afford to take on so many new students?

Williams said that concern has been on HBCU presidents’ minds for years as enrollments have steadily risen. But the post–affirmative action application spike has put their capacity in stark contrast to predominantly white institutions they’re now in closer competition with.

“The [enrollment] boost has created another challenge for our institution, and that is infrastructure,” he said. “It is certainly a positive thing, but the presidents at all our institutions worried about whether it can be sustainable.”

Thomas said that Morehouse exceeded all of its enrollment targets this fall; the current student body of 2,584 is nearly 300 students over the number they’d budgeted for. He said the college implemented a three-year on-campus residential requirement for students in 2016, but enrollment growth forced them to abandon it due to lack of housing.

“We have a real limitation on how many students we can physically support, and the same goes for Spelman, Howard, Morgan State and many more,” Thomas said. “Those are issues that more funding would solve.”

Despite receiving a whopping 12,000 more applications than last fall, North Carolina A&T, the largest HBCU in the country, actually enrolled a smaller class this fall than last. That’s partially to avoid incurring another fine from the state Legislature, which enforces a limit on the university’s out-of-state student enrollment, A&T spokesperson Todd Simmons said.

But it’s also because they don’t have the housing or infrastructure to grow right now. Over the past two years, the university has purchased six off-campus apartment buildings, and work on a 405-bed residential hall is nearing completion. The new housing is crucial; in January, officials had to relocate hundreds of students to hotel rooms after the heating systems in dorms malfunctioned.

“We’re growing incrementally, in ways that we can manage,” Simmons said.

Thomas, the Morehouse president, noted another issue that can result from the influx of applications: If HBCUs can’t afford to accept more students, they will simply become more exclusive. In 2020, Morehouse accepted 75 percent of applicants; this year that number fell to 43 percent, he said.

“We don’t want to present exclusivity as a virtue, like so many of the Ivy League–type colleges,” he said. “HBCUs have always been about giving opportunity to the most people possible. We don’t want to lose sight of that as we start to become more competitive.”