By Bianca Quilantan

Leaders of the nation’s historically Black colleges aren’t sold on either Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, even though both candidates tout their support on the campaign trail.

School presidents — usually key in galvanizing local communities to vote — have stayed uncharacteristically quiet this election due in part to the candidates’ thin policy agendas and concerns about how their historically underfunded institutions will benefit. Their silence risks the loss of an influential force in Black communities just two months before the election.

“As a president, we should say who is speaking to our issues, and then we should tell our constituents to say, ‘We need to vote for people who will work with our issues,’” said Walter Kimbrough, interim president at Talladega College in Alabama. “We do understand the symbolism and the historical significance of what is happening. But we still have real policy issues and items that we want to have addressed.”

And yet Democrats have a tangled history with the institutions’ leaders, who don’t formally endorse candidates but whose schools rely heavily on federal funds. The Obama administration initially suggested cutting funding to Black colleges and House Democrats declined to meet some Biden administration requests to direct more money to HBCUs. These actions stung.

Trump, as president, vowed to make HBCUs a top priority. He authorized millions in funding, including for scholarships and research. He also returned a Black colleges initiative from the Education Department to the White House, an HBCU demand. President Joe Biden surpassed that funding with billions in additional investment. But HBCU leaders want guarantees Harris will continue on that track and prioritize issues like college affordability and student debt, which affects a majority of their students.

“By this time in 2020, we’d had all the discussions and we knew what they agreed with and what we didn’t agree with,” said Lodriguez Murray, senior vice president of government affairs at the United Negro College Fund, the nonprofit that represents private HBCUs. “Because this campaign has been much more personality focused than policy-focused, you don’t have that galvanizing force of, ‘I have talked to them about this substantively, and I know that they are invested.‘“

The schools carry an outsized influence in their communities. The institutions produce nearly 20 percent of Black graduates, often serve as polling places and play a critical role in educating voters in their communities — particularly in Southern swing states, such as Georgia and North Carolina, where many HBCUs are located.

“HBCUs have been instrumental in setting up polling; they’ve also done voter registration drives, they have stepped in and filed lawsuits when students were not allowed to vote in some Southern counties,” said Marybeth Gasman, a leading HBCU expert who heads the Center for Minority Serving Institutions at Rutgers University. “I also hear the leadership of HBCUs regularly telling their students to vote, telling them to encourage others who they know or in the community to vote.”

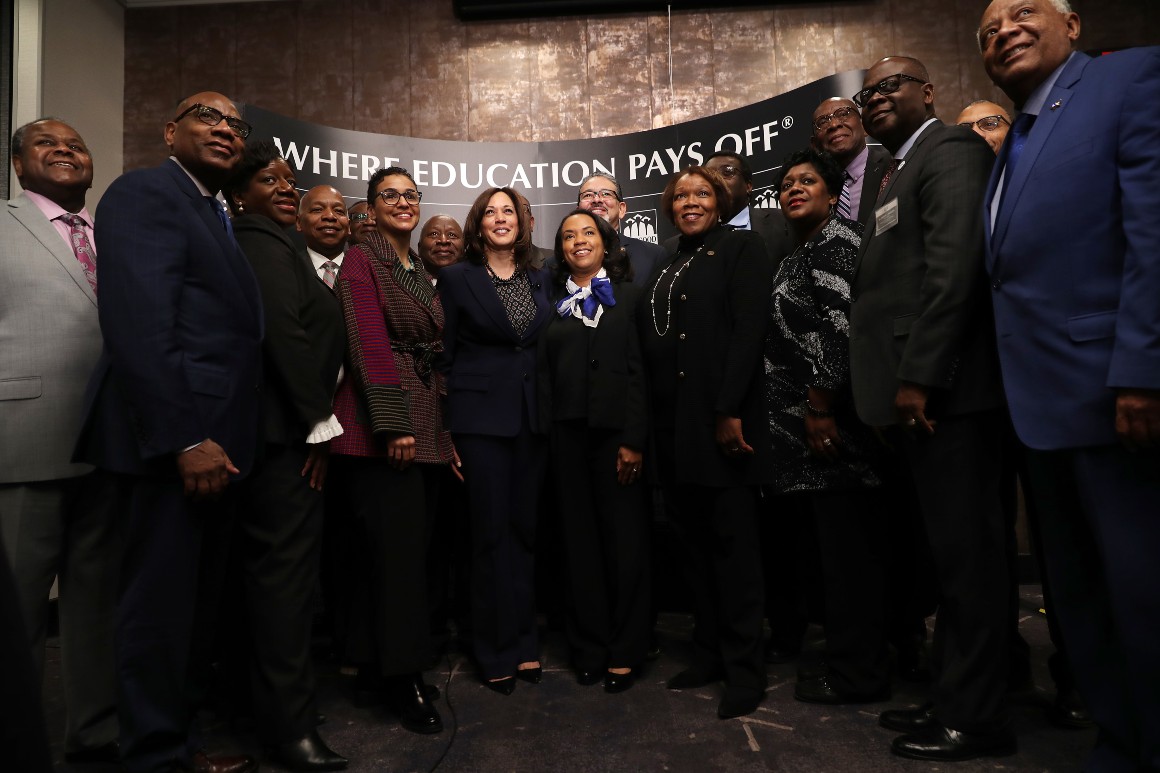

Both candidates appear to recognize the power these colleges hold in garnering votes. Trump regularly flaunts his record on HBCUs in his pitches to Black voters, while Harris hired a former president of an HBCU to lead her outreach to the institutions. She credited the success of the 2020 Biden-Harris ticket to HBCU student turnout.

“They do a very important job and a great job,” Trump said of HBCU school leaders at a June campaign stop in Detroit. “So I got you long-term financing and I think all of them are voting for Trump. … I’d say 99 percent of them.”

Trump signed a bill in 2019 that reauthorized $225 million in mandatory funding to minority-serving institutions, which included $85 million in recurring funds for HBCUs. That money supports efforts like university scholarships, faculty research and other programming. But he faced criticism from some HBCU advocates for budget proposals that called for cutting programs on which the schools rely.

“These institutions are a vital part of our country’s future, and [Trump] is committed to keeping them strong, keeping them funded, and making sure they continue to succeed,” said Janiyah Thomas, the Trump campaign’s Black media director.

Biden provided significantly more support to HBCUs. They received more than $16 billion in funding under him, including emergency grant dollars after scores of institutions faced bomb threats. The administration also sought to highlight past wrongs such as a $12 billion funding disparity between historically Black colleges that received land grants and their peers.

“The most offensive statement I’ve heard was when Mr. Trump said that he had done more for HBCUs,” said Glenda Glover, former president of Tennessee State University, who is leading the Harris campaign’s HBCU Initiative. “That’s just absolutely not true.”

Glover shrugged off the leaders’ silence. “Many of them are happy to participate in voter registration and voter mobilization efforts, but we haven’t asked anybody to take a side yet,” she said.

School leaders have played more vocal roles. Howard University’s former president, for example, touted Harris’ nomination for vice president as an “extraordinary moment” for the college.

But historically Black colleges face a balancing act since appearing too partisan could jeopardize their federal funding or nonprofit status. Howard in July warned its faculty, staff and students to “avoid any inadvertent attribution of political campaign activity to the school ” because it “could have significant consequences that would jeopardize the financial future of the University.”

Rep. French Hill (R-Ark.), who co-chairs the HBCU caucus, attributed such discretion to political savvy. “If your institution is a frequent user of federal programs and positioning itself to make appropriations requests to the Congress, I don’t know why you would want to get in the middle of presidential politics with a super high profile,” he said.

But he also disputed the idea there was a “retaliation-type risk” for administrators who work with either presidential campaign. “Both campaigns, frankly, have a strong message to talk to African Americans who are concerned about HBCU financial viability,” Hill said.

The institutions want to hear more about college affordability, funds for aging infrastructure and an increase in the maximum Pell Grant award, which is reserved for the nation’s lowest-income students. More than 70 percent of HBCU students are eligible for it and more than half of their students are the first in their families to go to college.

“We are very grateful and acknowledge the past support that we’ve gotten on these campuses, but the problems in terms of infrastructure are really dire,” said Rep. Alma Adams (D-N.C.), co-chair of the HBCU caucus.

Adams, who taught at Bennett College, a private women’s HBCU in North Carolina, said voters would welcome details on Harris’ HBCU priorities.

“Students want to know,” she said. “Faculty, staff, the community wants to know.”