By Sara Weissman

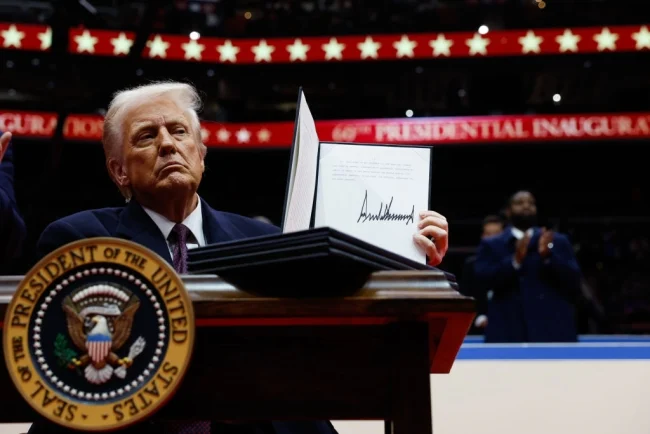

On his first day in office, President Donald Trump rescinded a slew of Biden-era executive orders and actions that he deemed “harmful.” In his order disbanding the initiatives, he slammed the former president for injecting diversity, equity and inclusion work “into our institutions,” calling DEI a “dangerous preferential hierarchy.”

Among the programs Trump slashed were initiatives Biden created to support Hispanic-serving institutions and tribal colleges and foster greater collaboration between federal agencies and the institutions. Another initiative that included “breaking down barriers” to federal funding for predominantly Black and historically Black colleges also bit the dust. That same week, federal webpages with information about HSIs and tribal colleges went dark.

Trump’s early moves raise questions about how colleges and universities with a federally recognized mission to serve underrepresented students will fare under the new administration. Leaders of these institutions wonder to what extent government officials see their colleges as entangled with the DEI principles Trump is working so hard to root out. They’re also asking themselves what it would take to change lawmakers’ minds before key funding streams and programs suffer. Some advocates for minority-serving institutions argue they shouldn’t fall under the president’s definition of DEI and are distancing themselves from the term. Some conservative thinkers argue these institutions don’t have to worry; they’re not the president’s target in his attacks on DEI.

Such institutions, whose designations were created under federal statute decades ago, have distinct histories and funding structures. To qualify for designated federal funding, Hispanic-serving institutions, Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–serving institutions, and predominantly Black colleges all have to meet specific enrollment thresholds for underrepresented student groups, while HBCUs and tribal colleges exist by charter and have no such requirements.

But these colleges and universities are united in a moment of precarity. According to one estimate, nearly 900 colleges that serve millions of students are considered minority-serving institutions.

Leaders of these institutions are “looking for clarity, and I think right now, we don’t have so much to give,” said Deborah Santiago, CEO of Excelencia in Education, an organization focused on Latino student success. She’s being bombarded by questions from HSIs about how to discuss their mission to recruit and serve Hispanic students without running afoul of the DEI bans.

Santiago is urging calm because she believes the administration’s intentions toward their colleges remain unclear. She noted that when President George W. Bush was elected, he rescinded former president Bill Clinton’s White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics (where Santiago worked as deputy director) but later released his own version. She’s also seen federal webpages temporarily go down during presidential transitions.

“I’ve been trying to field conversations where people are saying, ‘Are HSIs under attack?’ It’s a little premature to say that,” Santiago said. She doesn’t rule out that campus leaders’ fears could be realized, “but I wanted to take the time to educate our constituency about whether those things were direct attacks, and I don’t think they were.”

Others are preparing for the worst. Yolanda Watson Spiva, president of Complete College America, an organization dedicated to raising college completion rates that works with HBCUs and other institutions, is skeptical any of them are safe.

“I think that we should presume and expect that their very existence is under threat, the missions that they’re seeking to advance are under threat, and that funding for any of the programs and initiatives that they perpetuate are potentially ripe for rescission as well,” she said.

Fears for the Present and Future

Some MSI, HBCU and tribal college advocates say they’ve already been affected by Trump’s whirlwind first weeks of new policy.

Antonio Flores, president and CEO of the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, said Trump’s move to axe Biden’s initiative to support HSIs, signed just last year, was a “big deal.” Biden’s executive order, which hadn’t yet been implemented, would have created an advisory council on how federal agencies could invest more in HSIs and build up their capacity and infrastructure. It followed a Government Accountability Office report last year that found these institutions are saddled with millions of dollars of deferred maintenance.

“It was the first time in history that the president of the United States recognized formally through executive order the importance of HSIs, for the national interest and economy, the workforce and so forth,” Flores said. “Symbolically, it definitely does mean a great deal.”

He’s hoping to “regroup with the administration” and encourage them to reinstate the initiative.

Other Trump policies—though not specifically targeted at MSIs, HBCUs or tribal colleges—have sent shock waves through these institutions, like the federal funding freeze, which was rescinded after a federal judge blocked the move. If allowed, the freeze would be a blow to many of these institutions, which tend to lack large endowments and depend heavily on tuition dollars. That same memo called for a review of federal programs to ensure compliance with Trump’s policies, including his executive order that federal agencies curb DEI work. Recent reports of Trump’s plans to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education also bring fresh worries about possible disruptions to students’ federal financial aid at institutions where many rely on Pell Grants, financial aid for low-income students.

For some of these colleges, “if they are starved fiscally in any way … it could actually have an impact on those institutions’ existence,” Watson Spiva said.

Their federal research dollars could also be at risk—or delayed—because of “pre-emptive compliance” or overcompliance from federal agencies scrutinizing all their allocations, said Andrés Castro Samayoa, associate professor of higher education at Boston College. The National Science Foundation, for example, is reviewing its research projects to ensure they don’t fly in the face of Trump’s anti-DEI order, by looking for a list of flagged terms including “female” and “male dominated.”

What if federal agencies become “unable to fund Indigenous communities because the word ‘Indigenous’ is triggering?” asked Cheryl Crazy Bull, president and CEO of the American Indian College Fund, a scholarship provider for Native American students. She noted that rural communities more broadly would suffer if tribal colleges lost funding.

She finds the anti-DEI climate creates a chilling effect even on nongovernment funders. She said the American Indian College Fund lost two scholarship programs, which supported about 100 students, because organizations pulled their support.

“Naturally, we’re concerned that there’s this ripple effect,” she said.

Separate From DEI

Even more frustrating to Crazy Bull and other tribal college advocates is that, as far as they’re concerned, tribal colleges have nothing to do with DEI. They argue that belonging to a tribe is separate from race or ethnicity; tribes are sovereign nations, yet their higher ed institutions could suffer based on a fundamental misunderstanding of their identity.

Ahniwake Rose, president and CEO of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, said in a statement to Inside Higher Ed that her organization isn’t especially concerned about Trump revoking Biden’s initiative to support tribal colleges and universities—versions of it have been rescinded and reintroduced across administrations. But her “greatest concern” is that Trump cut the initiative in a list of other Biden executive orders with the word “equity” in the title, symbolically lumping them together.

“To be clear, the conversation around diversity, equity, and inclusion is entirely separate and distinct from the matter of Tribal Sovereignty and the Nation-to-Nation relationship between Tribal Nations and the Federal government,” Rose wrote. She called on Trump to sign a new executive order that “reaffirms the importance of TCUs as extensions of the federally recognized Tribal Nations that charter them.”

Santiago similarly argued that HSIs aren’t practicing DEI, at least in the way Republican lawmakers define it.

DEI is taken to mean “communities of color … are looking to get some benefit that they haven’t earned,” she said. “And I think … HSIs probably deserve to be cautious about being put under that.” She noted that while HSIs, by definition, have student bodies that are at least a quarter Hispanic, they serve all kinds of students.

Flores framed supporting HSIs as a workforce development issue. He noted that Latinos are projected to make up 78 percent of people joining the U.S. workforce between 2020 and 2030, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

“The more these institutions are able to prepare those new entrants to the workforce for the new jobs of our economy, the better off the entire nation is,” he said. HSIs train disproportionate numbers of low-income and first-generation students of all backgrounds, “and that has nothing to do with DEI. It has everything to do with uplifting the talent pool that all of those individuals represent for the country.”

Safe From the Crosshairs?

But will Trump administration officials see it that way, or will they see these institutions as a part of the DEI infrastructure they’re trying to quash?

Some conservative think tanks, including the Manhattan Institute and the American Civil Rights Project, have previously proposed abolishing MSIs and expanding funding for low-income students instead. But other conservative thinkers believe Trump is unlikely to go after those institutions. Even if he did, they say Congress generally controls the purse strings for the money allotted to HBCUs and tribal colleges.

Frederick Hess, senior fellow and director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, said ideologically, he doubts the Trump administration has a problem with the idea of “an institution that has a historic mission,” given Trump has previously touted his support for HBCUs.

Instead, he said that the president is taking issue with “particular programs or practices that create hostile learning environments, that label some students as oppressors, that are explicitly political rather than educational in their agendas,” Hess said. He suspects MSIs, HBCUs and tribal colleges’ programs might be subject to that scrutiny, alongside other higher ed institutions.

Preston Cooper, a senior fellow at AEI focused on higher education, agreed with Hess that MSIs seem unlikely to be “in the administration’s crosshairs.”

“I think that the sorts of institutions that the Trump administration is really not happy with and might want to go after are more the very elite, very wealthy institutions of the likes of Columbia and Yale,” Cooper said.

Nonetheless, amid all this uncertainty, Watson Spiva said some of the institutions she’s working with are thinking through different case scenarios: What programs would they need to cut or merge if they receive less federal funding? How would they support students if the Education Department were abolished and financial aid was disrupted?

Flores said he’ll continue lobbying for more funding for HSI capacity-building and infrastructure, among other legislative priorities. The association is also being “proactive” about building up partnerships with foundations and corporations, so “some of the programs that might diminish on the federal side can be complemented by private sector investments.”

And to government and nongovernment funders, he’ll keep making the case for HSIs and their value to the U.S. economy, outside of a DEI context.

“We don’t have to be permanently attached to words that are hindering the advancement of the very communities that we want to make sure have a shot at the American dream,” he said.