Poetry and football. Two words you don’t often hear in the same sentence.

One is a lyrical, niche art form. The other is a violent, mass-consumed sport. There’s something discordant about putting them together, like a mash-up gone wrong or two mismatched people on a bad date.

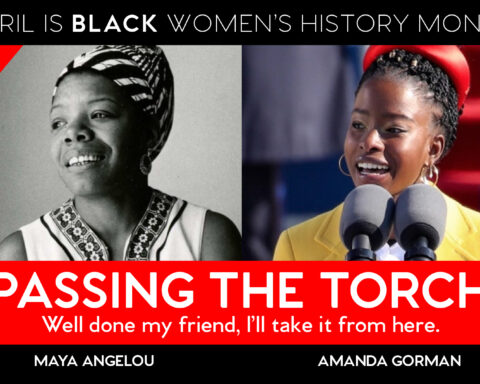

And yet Amanda Gorman, fresh off her stunning appearance at President Biden’s inauguration, will recite an original poem today at Super Bowl LV in Tampa. It’ll mark the first time poetry has been an official part of America’s biggest unofficial holiday.

Poetry has no business at a football game, you might say. Football games are for stirring renditions of the national anthem, neck-twisting military flyovers, the unfurling of vast American flags at stadiums packed with cheering fans. Pageantry, not poetry.

Poetry, on the other hand, is for Elizabethans, swooning lovers, starving writers and dreamy prep school boys under the spell of Robin Williams. It is traditionally consumed quietly, in a personal pact between poet and reader, without marching bands or Bud Light commercials.

The two seem SO different. After all, football is measured in yards, poetry in meters.

There’s no crying in baseball. And there’s no poetry in football. That’s the perception, anyway.

The perception is wrong.

“At their best, football and poetry both reach sort of a state of grace,” says Quentin Ring, executive director of Beyond Baroque, a literary arts center in Venice, California, where Gorman took poetry workshops as a teenager. “When you see somebody like Tom Brady when he’s in the zone, it’s sublime. And poetry is also something that large numbers of people can be enraptured by.”

Consider:

Football and poetry have a history

“Football combines two of the worst things in American life,” George Will once said. “It is violence punctuated by committee meetings.”

Poetry, on the other hand, has been called nothing less than “the history of the human soul.”

But yes, there is poetry in football. There’s the graceful arc of a perfectly thrown spiral, the slow-motion ballet of a halfback weaving through tacklers, ESPN’s Chris Berman rhapsodizing about “the frozen tundra of Lambeau Field.”

There’s also history.

The Baltimore Ravens are named for “The Raven,” the famous poem by Edgar Allan Poe, who spent the later part of his life in the city.

The climax of the Marx Brothers’ 1934 movie “Horse Feathers” is a college football game in which Chico calls out plays with rhyming verse. “Hi diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle,” he says, “This time I think we go through the middle.”

And the battle hymn of the Raiders franchise, dating back to their early days in Oakland, is “The Autumn Wind,” a poem adapted by Steve Sabol and narrated by NFL Films’ John Facenda, whose thunderous baritone earned him a nickname, “The Voice of God.”

Its last verse goes like this:

The Autumn Wind is a raider,

Pillaging just for fun.

He’ll knock you ’round and upside down,

And laugh when he’s conquered and won.

It’s not Shakespeare, but Raiders fans still blast the poem from their trucks at tailgates.

NFL players write poetry

Cleveland Browns defensive end Myles Garrett, the first overall pick in the 2017 NFL draft, is 6-foot-4, 272 pounds and hell on opposing quarterbacks.

He also loves the poetry of Maya Angelou, and writes poems in his spare time.

“If I’m feeling stress or anxiety, I’ll escape into another world. With books, you’re going on an adventure, imagining and wondering. Poetry is different,” he told ESPN. “When you’re a poet, or reading poems, you feel every single word.”

Garrett is just one of numerous NFL players who have dabbled in writing verse.

Another, Seattle Seahawks receiver Tyler Lockett, wrote a poem, “Reality vs. Perception,” about social injustice and the prejudices Black men face in America.

It goes, in part:

When I look in the mirror, I see more than a Black man

But what do you see, America?

An entertainer? An athlete?

What else do you see?

A gangbanger? A drug dealer? A criminal? A lowlife?

Why not a lawyer? Why not a doctor? Why not a son? Why not a father?

A video of Lockett and other star NFL players reciting the poem is on the NFL’s website.

Even Tom Brady has been known to share poetry as a way of getting fired up for a game — as he did on Instagrambefore his last Super Bowl appearance two years ago. It must have worked. He won.

Poets have written poems about football

Baseball, with its sepia-toned mythology and leisurely rhythms, has long been seen as the more literary sport. From “Casey at the Bat” to John Updike’s tribute to Ted Williams at his last home game, writers have waxed poetic about its sun-dappled ballparks, crafty pitchers and heroic batters striving for bursts of glory.

Football, not so much.

After all, Alfred Lord Tennyson didn’t write, “‘Tis better to have played and lost to the Jacksonville Jaguars than never to have played at all.”

But there is a vibrant subgenre of football poems by professional poets. Their verses describe graceful young bodies in their prime, touch football games in the street and fans huddled on rickety school bleachers on Friday nights.

One, “football dreams” by Jaqueline Woodson, begins like this:

No one was faster

than my father on the football field.

No one could keep him

from crossing the line. Then

touching down again.

Coaches were watching the way he moved,

his easy stride, his long arms reaching

up, snatching the ball from its soft pockets

of air.

Poetry spoken aloud has a ‘physicality’

This evening in Tampa, Amanda Gorman will not be reading a poem about football.

Instead she will recite an original poem recognizing three honorary captains at the Super Bowl — a nurse, a teacher and a veteran — “who served as leaders in their respective communities during the global pandemic.”

It’s just the latest in a flurry of recent triumphs for Gorman, the nation’s first-ever youth poet laureate.

Ring remembers Gorman from her years in the poetry program at Beyond Baroque and was immediately struck by her precocious talent.

“It was pretty clear that she was destined for great things,” he says.

Ring couldn’t have imagined those great things would include bringing the ancient art of poetry to America’s biggest sports spectacle.

But he says the pairing of poetry and football is not the shotgun marriage it may seem. Like football, spoken-word poetry is a communal activity. And like football, its carefully chosen words can land with impact.

“There’s a physicality to it,” he says. “People can actually feel it when Amanda is reading her poetry.”

Some, watching Gorman tonight, will feel it. Some will shrug and turn back to their chicken wings. But the Super Bowl will never be quite the same.