The era of good feelings enjoyed by President Joe Biden and the Democratic Party’s progressive wing will face a stern test of its staying power as the administration pushes forward into the next phases of its big-ticket policy agenda.

Biden’s first hundred days in office saw the passage of his $1.9 trillion Covid relief and economic stimulus package, along with the escalation of an unprecedented mass vaccination campaign that appears, at last, to be beating back the coronavirus pandemic. The success of those high-stakes government interventions has, in the eyes of many on the left, laid the groundwork for broader enhancements to the social safety net on a scale to match the ambitions of Democratic Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, author of the New Deal, and Lyndon B. Johnson, who enshrined Medicare and Medicaid as part of his Great Society.

But the heady comparisons are, at most, premature, and more likely wishful thinking. Even if Biden’s aspirations have been severely underestimated, the governing environment today — even with Democrats in control of Congress — is less conducive to the kind of enduring rewrites to the American social compact composed by his predecessors.

Still, it is undeniable that Biden has so far succeeded at a practice that either eluded or had been largely dismissed as a useful practice by more recent Democratic administrations. The most unexpected political success of Biden’s first three months in office is not a healthy approval rating or even the broad popularity of the “American Rescue Plan.” It is, instead, the strategic work that seeded those outcomes — the building and prodding along of a fragile but effective coalition within his own party.

Now, though, comes a more intricate, complicated political challenge. The green shoots of economic recovery, juiced by March’s relief package, has created a welcome problem for Democrats. Absent the consuming impetus for action, both party centrists and progressives figure to be emboldened to drive tougher bargains on new legislation.

Worries of a lost summer

With Republicans electing to effectively sit out talks with Democrats in Washington, Biden has pressed forward, refusing to be drawn into protracted, dead-end negotiations. His deeply rooted, near ideological devotion to finding bipartisan consensus has, for the moment, been pacified by the realities of the day (and lessons from the past). Instead, Biden has focused his deal-making efforts on lawmakers from within own party, whose slim congressional majorities mean that a single Senate defection or the loss of even a minor bloc of House members would be enough to grind his presidency to a halt.

As the first 100 days spill out into what leading progressives worry could become a lost summer, there is a growing sense that the window for generational action on issues like climate change is closing. Biden is loath to squander the opportunities presented by what his chief of staff, Ron Klain, has described as a series of overlapping crises, but his willingness to take on more ambitious projects — the kind that fit under Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s heading of “big, structural change” — is less plain to see.

What’s clearer is how he’ll go about his business. Biden is a politician in the purest sense and his ability to position himself, through a combination of aggressive outreach and intuition, within touching distance of both poles of his party is a unique talent. He did not ride into the White House on the shoulders of a movement, but he clearly understands their power, just as his decades of experience counting votes in the Senate made clear their limitations.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez nodded to both realities in a recent virtual town hall, when she said the administration has “definitely exceeded expectations that progressives had,” before pointing to the crossroads ahead.

“I do think that the infrastructure plan is too small, but I think that (Biden’s) vision was right — I think that what he advanced as some of these key goals were the right ones and they were admirable ones,” Ocasio-Cortez said. “But I have real concerns that the actual dollars and cents and programmatic allocations in the bill don’t meet the ambition of that vision of what’s being sold.”

Ocasio-Cortez and her allies in the increasingly effective Congressional Progressive Caucus, led by Washington Rep. Pramila Jayapal, have been measured in their public remarks. In a way, their positioning reflects Biden’s own calculus — that there is little margin for error and fights will need to be chosen with care, or else they’ll consume and undermine the coalition.

A test of trust

After Biden secured the Democratic presidential nomination early last April, when Sen. Bernie Sanders dropped out of the race and quickly endorsed him, the Biden team and leading progressives carved out a strategic partnership rooted in a shared desire to unseat Trump and launch a coherent, effective and equitable pandemic response. But baked into their election-winning alliance was another understanding: that relationships mattered and, down the line, confrontation was inevitable.

So, they set about to create some padding.

First came the “unity task forces,” working groups with members appointed by Sanders and Biden, charged with hashing out policy differences and establishing some kind of framework for future action. The meetings produced some meaningful consensus, mostly on climate change policy, but were more valuable to both sides as social exercises or dry-runs for the intra-party debates to come.

Then, after the election, another hurdle: staffing the White House and administration. Despite installing many of the usual suspects — a handful of them distrusted or even loathed on the left — in the highest ranking jobs, Biden’s team also embedded a new generation of progressive policy thinkers into less flashy but influential roles, setting them up well not only for the coming months and years, but to begin a slow transition toward a more progressive-minded Democratic policy establishment.

Those early moves are inextricable from the confrontations on the table now, creating a more hospitable environment for constructive debate and a base of goodwill — and good faith — that could spare the party a return to its recent history of more corrosive clashes.

For example: Though the parameters of Biden’s infrastructure package, the “American Jobs Plan,” are still being drawn and the sticking points only vaguely in focus, the size and scope of its climate investments are already picking at doubters on the left.

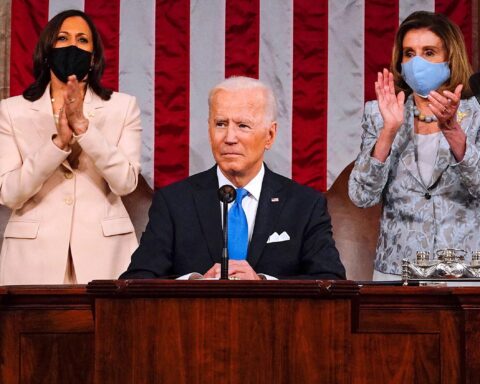

Biden has said he wants to cut US greenhouse gas emissions by 50%-52% from their 2005 levels by 2030, but his proposed spending — $2 trillion over eight years — is a retreat from his campaign pitch, which called for the same amount over just four years. There is no Republican support for anything close to either outlay, which means Democrats will — again — ultimately be negotiating with themselves in an effort to get to the 50 votes (plus Vice President Kamala Harris’s tie-breaker) to pass the final bill through budget reconciliation rules in the Senate. Anything less than unanimity in the upper chamber and something close to it in the House would kibosh the plan, whatever it looks like.

A group of progressive organizations, including Justice Democrats and the Sunrise Movement, highlighted the pressure points in a memo published this week that graded Biden’s first 100 days and spelled out the left’s agenda going forward.

The authors described the American Rescue Plan as “an important step toward stabilizing the country” and cheered the administration for acting decisively when it became clear Republicans weren’t coming onboard. They also highlighted Biden’s rapid Covid response, his early rhetoric on climate change and the creation of a White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy, choosing progressive Deb Haaland to run the Interior Department and his recent commitment to fully withdraw US troops from Afghanistan.

But its kicker, after listing the issues where Biden had yet to move, was stark.

“The honeymoon,” they wrote, “is over.”

Rhetoric vs. reality

The left’s agenda is indeed broad, ambitious and, to date, largely unfulfilled. There is also an emerging gap between Biden’s spoken words and those that appear, on paper, in his legislative agenda.

In his address to a joint session of Congress this week, Biden made the public case for boosting the minimum wage and passing the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, a top priority for labor and the left. He also touted what could be his signature achievement: an expansion of the poverty-busting child tax credit, written into his Covid relief bill, that he wants to extend another four years. (Its supporters, a broad-based group in the Senate, want to make the benefit permanent.)

Biden also discussed lowering prescription drug prices by giving Medicare the ability to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies, a curious inclusion given the longtime progressive priority was left out of his first draft of the “American Families Plan,” the legislation Democrats have teed up to follow their infrastructure bill. Whether his remarks were, as STAT News described them, “an empty call to action,” or a signal that he was giving way and inviting pressure to change course is one in a growing collection of open questions facing progressives, who have been welcomed — literally — into the Biden White House.

But no amount of high-level meetings and robust, all-hours communication with progressive leaders can paper over the fact that the federal minimum wage remains unchanged, there has been no talk of expanding Obamacare to include a public option, as Biden proposed on the stump, or that a federal voting rights reform bill is stuck in the congressional muck. The Senate’s 60-vote filibuster remains in place and Biden doesn’t appear to have the appetite to pressure the moderate Democratic holdouts in the chamber, like Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema, to climb down from their positions in support of it.

And without cracking that lock, the “go big” mantra embraced by the White House will remain just that: sloganeering. Biden, of course, can only do so much. There are 50 Democratic senators, not 60 — like President Barack Obama had for a brief period after taking office — or closer to 70, which helped FDR and LBJ get their signature programs over the line. But the new left is different from the last generation of liberals. They are younger, generally, and cut their political chops in the unrelenting cauldron of movement politics. That movement has matured over the past few years, and now has, in Sanders, the Budget Committee chair, one of its leaders in a seat of remarkable influence.

None of this is news to the White House, which navigated those tensions in the run-up to the passage of the American Rescue Plan and avoided any headline-grabbing brinksmanship over issues like stimulus checks early on in the process. When the Senate parliamentarian ruled out a minimum wage hike to $15 an hour, effectively striking it from the legislation, progressives fulminated but never threatened to pull their support.

That understanding of Biden’s domestic constraints and the left’s selective engagement on contentious foreign policy issues, like continued US support for Saudi Arabia as it carries out a deadly war in Yemen, has been critical to the President’s early success.

But there is a line between cooperation and capitulation — and as the next 100 days of the Biden presidency unfurl, progressives will need convincing that the President isn’t daring them to cross it.