Patti Eisenbraun had been anxiously waiting for the pandemic to subside so the dining room and patio at the Brown Iron Brewhouse would be bustling once again.

Yet the lights were off, and her business was closed here Monday — not for a lack of thirsty customers, but for a lack of employees.

“We went from 92 hours to 55 hours a week,” said Eisenbraun, who opened the brewery and restaurant in 2015 with her husband, after a decade of planning. “It’s a tough business model right now to be closed during those hours.”

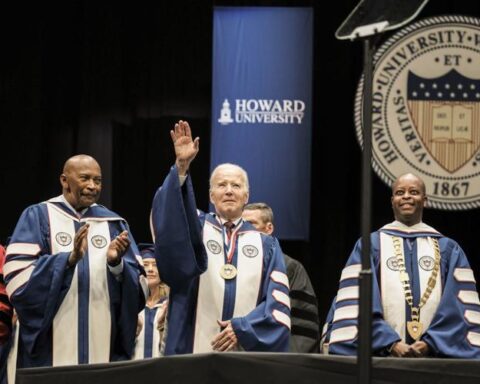

A labor shortage is one of the persistent headwinds facing President Joe Biden as he builds support for his economic agenda to invest trillions of dollars in new federal spending to move the country from relief to recovery. From restaurants and retail to manufacturing and construction, signs declaring “Now Hiring” hang outside businesses most everywhere you look.

“We’re trying everything we can,” Eisenbraun said. “There’s just not the people out there right now.”

From Washington Township, which sits less than an hour’s drive north of Detroit, the hiring challenges are a critical piece of the complicated economic puzzle facing the Biden administration. It’s a stark warning sign here in Michigan and across the nation, but one that White House officials argue helps make the case for their sweeping economic proposals.

It’s an open question whether the economic speed bumps — from a labor crunch to rising prices in the grocery store and at the gas pump — signal a short-term headache or a long-term challenge for the President. He visited Michigan on Tuesday to tour an electric vehicle center at Ford Motor Co., highlighting the new F-150 Lightning that adds an electric battery option to the highest-selling truck in America.

But just as Biden’s fortunes were tied to taming the coronavirus pandemic, so too are they linked to an economic recovery. The rest of his presidency will likely rise or fall on the strength of that rebound, creating a ripple effect for the congressional elections in 2022 and his agenda.

“Yes, he will be judged on how the economy is doing — as will all of us,” said Rep. Debbie Dingell, Democrat of Michigan. “So, our job is to work together and keep the economy strong.”

In an interview on Monday, Dingell said the labor shortage is very real — as are its root causes, including childcare concerns that could keep people from returning to work. She said lingering Covid-19 fears — particularly in a state only recently coming out of the grips of a springtime surge — as well as women leaving the workforce in droves also contribute to a labor shortage.

Asked whether she was optimistic about the economy, Dingell said: “I’m going to choose to be optimistic, and it’s my responsibility and everybody else’s to make sure we deliver on that optimism.”

But delivering on that optimism means fighting the unmistakable economic headwinds — many of which revolve around rebuilding America’s vanishing workforce.

“Throughout the pandemic there has been a need for workers and now we’re starting to see an uptick in the number of people that are coming in looking for work,” said Eva Garza Dewaelsche, president of SER Metro-Detroit Jobs for Progress, a workforce development organization. “There are a lot of jobs that are going unfilled, which is why we’re going to need job training.”

She added: “Finally, I see a bright light at the end of the tunnel.”

There are, of course, many reasons for optimism — economic and otherwise — as the country begins to move beyond mandatory mask policies and other restrictions imposed during the pandemic. But the economic recovery remains remarkably fragile so long as the fight against the coronavirus continues.

Margie Martin is an employment specialist in Detroit, matching workers to jobs. She’s on the front lines of one of the biggest policy questions hanging over the President’s economic agenda: Are government unemployment checks keeping potential employees on the sidelines?

“I don’t think so,” said Martin, who believes challenges finding child care, transportation to work and lingering fears of Covid remain looming factors driving the labor shortage.

“Obviously we’re going to have people that might take advantage,” she added, “but my own personal experience is that there’s other issues that don’t allow someone to get employment, like, a single mom doesn’t have a support system, or her kids are at home.”

A growing number of states — at least 14 and counting — have called for cutting off enhanced federal jobless benefits this summer. Michigan is now restoring its requirement for workers to show they are looking for jobs to receive benefits, a practice that was discontinued a year ago when the pandemic began.

“There is no longer a shortage of jobs,” said Brian Calley, president of the Small Business Association of Michigan. “I have never heard or seen this level of frustration and concern over the inability to find or fill open jobs.”

In the city of Sterling Heights, which sits just north of Detroit, Mayor Michael Taylor is a Republican who’s been watching the new President closely. He supported Biden in the election last fall and said in a weekend interview: “I’m very happy with my decision.”

But Taylor said the labor shortage is the biggest concern facing business owners.

“In the very short term, I think it’s a problem,” Taylor said. “It certainly seems to me that there are enough jobs out there that people who need to work can find a job.”

As the summer season begins, the lack of workers is coming into sharper view.

Eisenbraun is offering “a bounty program” for employees who recruit new workers. She also offers health care, dental care and a 401(k) plan — far more competitive than many restaurants or bars.

“Happy employees mean happier customer experience. Happier customer experience means more revenue,” she said. “It’s something that we’re investing in, but we’ve got to get these employees back here.”

She dismisses critics, including those in elected office, who blame employers for the labor crunch. She said that she and many other small business owners are being generous and creative to try and fill the open staffing positions.

“I think the misconception that I see from the politicians is that the reason why people aren’t going back to work is that the jobs aren’t worth it, that these are low-paying jobs,” Eisenbraun said. “But they aren’t.”