Saleemah Graham-Fleming had been told she wouldn’t be able to have children. That’s why she always called Sanaa Amenhotep, the oldest of her three daughters, a miracle.

The two loved each other fiercely: they had frequent “cuddle time” sessions and dedicated Friday girls’ nights. The teen would often join her mom for errands, riding in the passenger seat and snapping photos for her social media accounts, which she always kept up to date.

On April 5, Sanaa stepped out with her younger sister to take some pictures near their Columbia apartment, but she never came home, her mother said. Sanaa’s body was found on April 29, Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott announced. She had been shot multiple times. Sanaa likely met two males she knew and voluntarily left, but was later kidnapped, Lott said.

Days after the announcement, an 18-year-old and two minors were arrested and charged with kidnapping and murder among other charges, the Lexington County Sheriff’s Department said.

“It’s every parent’s worst nightmare,” Graham-Fleming told CNN. “Not only has it been devastating for me, but I have two other children who have been affected by this. So our whole family has been dismantled.”

Alabama’s biggest city has a growing gun — and homicide — problem

While national leaders sound the alarm over a recent surge in violent crime across major US cities that shows no signs of letting up, local authorities in Richland County say they’re fighting their own gun violence spike.

After Sanaa’s killing, Lott announced the arrest of two 17-year-olds in the May 27 shooting death of 18-year-old John Kelly. Days later, 19-year-old David Green was shot and killed at a party, and an 18-year-old was arrested and charged with murder. Earlier this month, Columbia police said they were investigating the fatal shooting of 19-year-old Trinity Sanders.

Richland, the state’s second most populous county and home to the capital city of Columbia, recorded a violent crime rate of more than 530 per 100,000 residents in 2019, according to FBI data. That was more than 60% higher than Greenville, South Carolina’s most populous county, and nearly 45% higher than the national average that year.

It’s now facing a gun violence “crisis,” the sheriff says, and many of the victims are teenagers. The county has already recorded at least 19 shooting deaths so far this year, according to the sheriff’s office — one more than last year’s total and on pace to also surpass both 2018 and 2019.

Eight of this year’s fatal shooting victims were 24 or younger — double what was recorded by this time in 2020 and four times what the same period in 2019 saw.

Louisiana residents grapple with gun violence gutting their communities

The increased violence continues across county lines.

In 2020, South Carolina logged its highest number of murders in more than six decades, since the state began keeping records, and a 51% jump from 2015, when it recorded 378 homicides, SC Law Enforcement Division Chief Mark Keel said in a June news conference.

This year will likely be worse, Keel said. Gangs, drugs and criminals’ access to guns are driving the surge, he said. They’re among key things President Joe Biden vowed last month his administration would crack down on in response to the nationwide spike in violence.

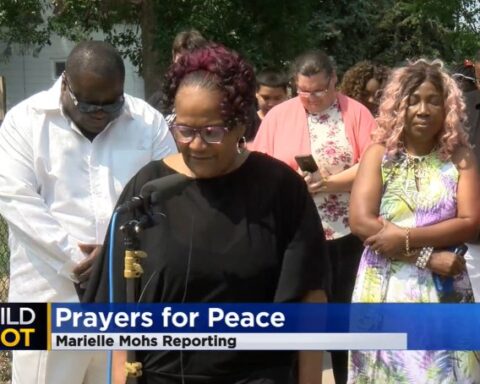

But those in Richland County aren’t waiting for outside help. Local authorities have appealed to their community for help in curbing the shootings. And residents — often themselves touched by gun violence — are organizing events to raise awareness of the problem, including the county’s first-ever gun violence prevention summit this weekend.

Pandemic shuttered teens’ outlets

Inside the small office Perry Bradley rents in one of Columbia’s highest crime areas, preparations were underway this month for the Gun Violence Prevention Summit he’s putting together Saturday.

Columbia police, the sheriff’s office and other community organizers have partnered with Bradley’s non-profit, Building Better Communities (BBC), to speak to youth in an attempt to slow down the killings.

“These kids are carrying firearms and they don’t know how deadly they are,” Bradley said. “Fourteen-year-olds, 15-year-olds, they’re actually killing each other out here in the streets and it’s really over nothing.”

The organization has worked for more than a decade with teens and has expanded its mission over the years. It now offers everything from life skill courses, food, shelter, clothes for court or job interviews to mental health resources and mentorship programs.

A stack of more than a dozen boxes filled with masks for the summit lined one corner of the BBC office. It’s a response to the coronavirus pandemic — which officials say is contributing to the gun violence spike.

The pandemic forced community centers, schools, libraries and other programs to close, which made it harder to reach out to teens, said Columbia Police Deputy Chief Melron Kelly.

“We missed the opportunities to intercede on the lives of young people that were going through crisis,” Kelly said. “So I think the default to that was a lot of times indulging in either social media or television or things that weren’t healthy.”

Richland County teen Chardonnay Jackson said frequent online posts about shootings normalize the violence and cause many other youth to have little regard for life.

“I feel like people don’t value other people’s lives because it’s just, they see people dying and dying and dying and it’s starting to get normal,” the 14-year-old said. “It’s normal for people to pass away. It’s normal for people to get killed.”

Some community members have focused on getting more teens involved in sports, which they say have always played a critical role in helping keep youth out of illegal activity. Playing football and running track and field was what has helped 17-year-old Desmond Martin stay focused, he said.

“You’ve just got to keep your head on straight,” he said. “You gotta make sure you make it home every day.” A close friend — a role model who was just two years older than Desmond — was shot and killed last year, he said.

“It was hard, but I kept going, I went hard in football, basketball, track, everything. I did it for him.”

‘I’m just fed up’

Longtime Richland County residents say while news alerts about shootings seem to have exploded recently, gun violence in the community has been a problem for years.

Pamela Dinkins can attest to that. Her 17-year-old son, who was preparing to graduate high school, was killed in 2015 after what Columbia police said was an altercation that “escalated and ended with the shooting.”

Biden warns of ‘more pronounced’ summer crime spike as he announces plan to tackle gun violence

Seven months ago, her husband was also fatally shot multiple times outside a convenience store. Dinkins, who’s scheduled to speak at the upcoming summit, said she founded an organization, Mothers Against Gangs and Guns (MAGGS), and most recently started the group Women Against Violent Encounters (WAVE).

That group, which works in collaboration with BBC, is made up of residents who meet weekly to discuss the latest incidents and steps they can take to address the problem. She joined BBC last month, adding to a growing number of local volunteers who have joined the non-profit to help fight the violence.

“I’m just fed up,” said Dinkins, surrounded by pictures of her son that adorn her living room walls. Down the nearest hallway, her son’s room remains nearly untouched, his basketball shoes still tucked neatly in one corner.

“The pain never goes away,” she said. “They say it gets better with time. That’s a lie.”

Though it may have been exacerbated by the pandemic, violent crime in the community has long been fueled by conditions of poverty and a vicious cycle of untreated trauma among youth that comes with the recurring violence, community members told CNN.

“Poverty creates invisibility in so many communities. People feel like they need to be heard and when they are heard, it’s only from the sense of violence,” Lester Young Jr. said. “How do we help people become visible? Invest money in these communities that have been neglected for generations.”

Young founded Path2Redemption, a non-profit in Richland County for formerly incarcerated individuals and at-risk youth, after he spent more than two decades behind bars for fatally shooting someone over a drug dispute.

He said many of the youth he works with live in low-income areas, in single-parent households and some didn’t have Wi-Fi during the pandemic to keep up with their classes. Teens in those types of environments, Young said, often turn to gangs and drugs for a sense of belonging and validation.

“There are a lot of deep core issues that we as communities and organizations have to be willing to address in order for us to curb gun violence in the community,” Young said.

Part of the change, residents say, must come from the top. For example, many here feel the community’s problems were not helped by Republican Gov. Henry McMaster’s recent decision to sign a bill letting people with concealed weapons permits carry their guns in the open. Others say they want tougher sentences for those repeatedly arrested for gun crimes.

Columbia City Councilman at-large Howard Duvall, the only one of the city’s six council members who responded to CNN’s request for comment, said city leaders are working to tackle the problem by helping to build the city’s economic base, offering a wider range of opportunity to residents, and providing more resources to the local police force.

In 2019, Columbia police implemented ShotSpotter, a gunshot detection system that Kelly, the deputy police chief, said has helped boost the department’s gun seizure numbers.

“We know that young people can get their hands on a gun very quickly, most through a burglary or someone that left their car unlocked,” Kelly said. “The availability of guns is just terrible.”

This year, Kelly said, the department hired an attorney who will be embedded in the U.S. Attorney’s office and will focus on prosecuting gun crimes in the city of Columbia.

But what drives gun violence — and has for decades here — is a lack of resources, Sheriff Lott and residents here say.

“There needs to be money for programs to go into these neighborhoods and help get these kids to do something positive,” Lott said. “Every child has something that they’re interested in doing. We just have to find out what that is and give them the means to do it. And if we don’t, they’re going to find something else to do.”

A call to action

For Kelly, with the police department, each loss feels personal.

“Probably over 90% of where the homicides happen in the city is where I grew up, North Columbia,” he told CNN. “Of those individuals that were murdered, over a vast majority of them looked like me. They’re African American males that grew up in my old neighborhood.”

The city is 40% Black. Columbia police say the suspects and victims in gunfire incidents tend to be “young, African American males” and the victims are between 21 and 23 years old. The killings, Kelly said, are often over something “very minor.”

“Conflict resolution was something that was taught in schools years ago that I think we’re missing now,” Kelly said.

“Those are things that are taught not only in the home, but also in the community, because it does take a village,” he added. “How do we better wrap our arms around the young people that most need us, even if they don’t even realize it?”

That’s what Bradley said he wants his organization to do.

“There’s no resources in our communities that help these young men and women out like they should,” Bradley said. “When people don’t care about you, you tend to stop caring about you. And when you don’t care about yourself, you don’t care about others either.”

With the help of local authorities and community members such as Young and Dinkins, Bradley said he hopes his organization and the summit can get more residents involved in the conversation about local gun violence and help pull youth out of illegal activity.

It’s a problem law enforcement alone won’t be able to solve, the sheriff said, urging more community members to get involved. The same message was echoed by the state’s top law enforcement leader last month as he cautioned for what may still lie ahead.

“Now’s the time to work together,” Keel said in June. “We cannot do it alone. As we’ve said many times before, this is not an issue where we can arrest our way out of it. We need communities to help if we are truly to make our nation, our state and our home safer.”

Residents in Richland County agree. Graham-Fleming says change begins with more programs that engage with the youth and keep them active.

“I don’t sit here with a holy grail book of all the answers, because I don’t have them,” she said. “But something has to be done, not just because it was my daughter. Just because it’s too many kids dying. Too many.”

She’s preparing to host a walk in honor of her daughter on August 7, three days after what would have been Sanaa’s 16th birthday.