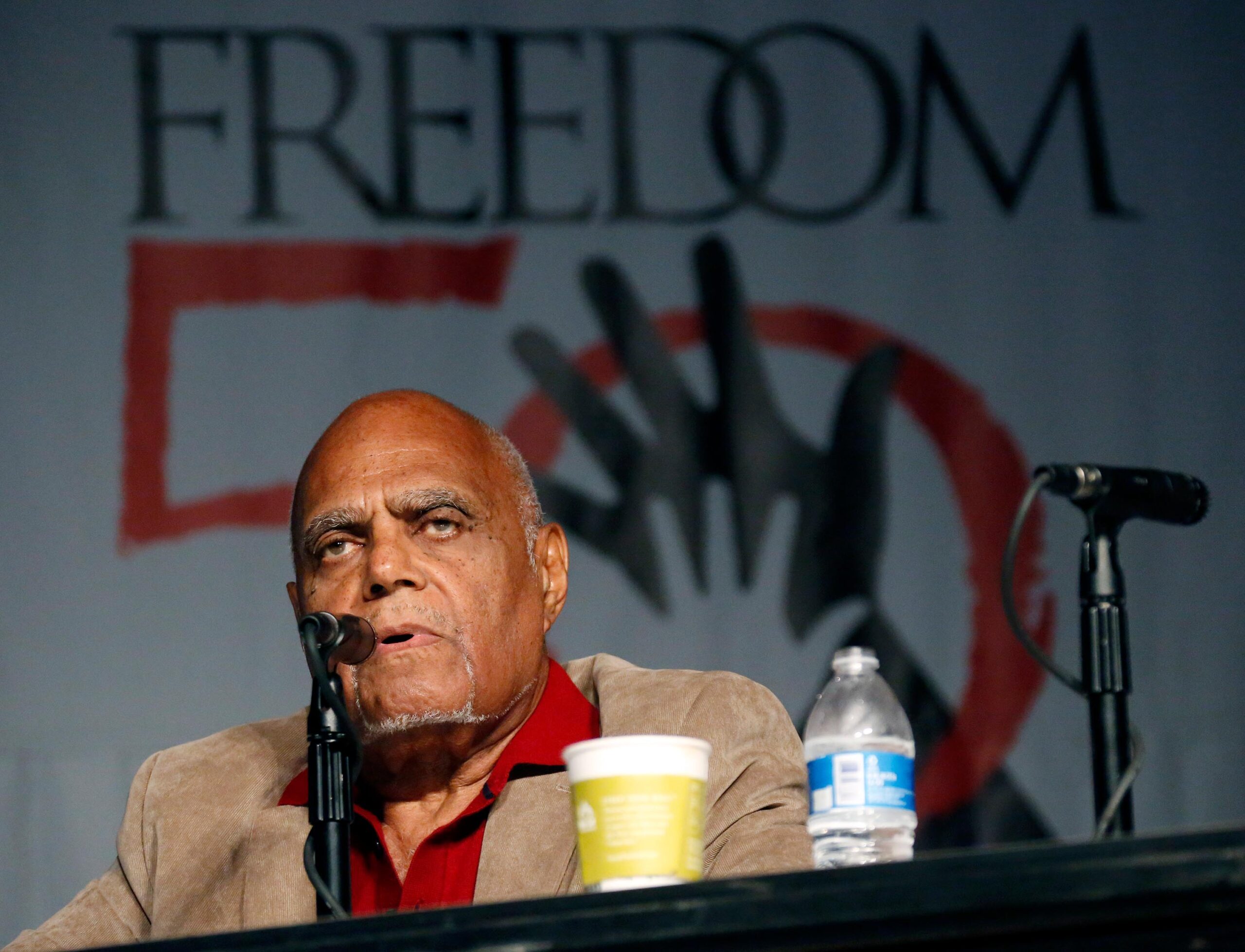

Bob Moses, who died this week at age 86, was an unconventional civil rights leader. He didn’t energize crowds with fiery speeches, and wasn’t known for leading marches, yet few leaders have inspired such veneration.

Moses helped put the Black struggle for voting rights on the national radar at a time when many judges, politicians, and ordinary Americans were indifferent to the issue. He was beaten numerous times and almost killed while registering Black voters in Mississippi in the 1960s. Still, he never gave up.

“Things looked pretty bleak back then as well,” said Diane Nash, a civil rights leader and former student sit-in leader who knew Moses. “Even in those days, when they were using literacy tests and poll tests and claiming that they weren’t doing it for racial reasons just like they do know, Bob can certainly be an inspiration for those working for freedom.”

As activists and lawmakers protest in Washington, DC, demanding that Congress pass federal voting rights legislation to counter state-level voter restrictions, Moses has left them a blueprint on how to win in the most hostile circumstances, civil rights leaders say.

President Joe Biden and former President Barack Obama praised Moses for his undying fight for voting rights.

Biden released a statement Monday saying Moses led with “uncommon grace, calm, and humility despite every bullet, arrest, and unrelenting brutality he faced.”

Biden dared the nation to continue Moses’s unfinished work, crediting him with helping dismantle the Jim Crow system that suppressed Black voters, and he urged Congress to pass the For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

“Let us build the coalition of Americans of every race and background that he once formed to meet the urgency of the moment,” Biden said. “And let us follow his towering legacy and ensure every American is treated with the dignity and respect they deserve.”

Obama said he was inspired by Moses.

“Bob Moses was a hero of mine,” Obama tweeted. “His quiet confidence helped shape the civil rights movement, and he inspired generations of young people looking to make a difference. Michelle and I send our prayers to Janet and the rest of the Moses family.”

A ‘consistent’ leader

Many of the tributes to Moses focused on his work as a voting rights organizer in Mississippi during the civil rights movement. It had a well-deserved reputation as the most harrowing place in the South for Black people to vote. When Moses arrived in Mississippi by 1961, only about 5% of voting-age Black people had been allowed to register to vote. In many counties, no Blacks were registered to vote.

Moses was instrumental in putting voting rights on the national agenda — by empowering ordinary people. He was a central organizer of Mississippi Freedom Summer, a project in which an interracial group of student volunteers was invited to come to the state and work alongside local organizers to register Black voters. He served as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

One of Moses’s key insights is that ordinary people can become powerful agents of change. He was influenced by the organizer Ella Baker, who said, “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.” Moses was known for partnering with and empowering local leaders to take over long after the media and other civil rights activists had left.

Melanie Campbell, president of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation, said she admired Moses for his “consistency” in the voting rights movement.

Campbell said while she never met Moses, his legacy should teach today’s activists that the fight for voting rights or civil rights can’t be won overnight.

“He never left the movement,” Campbell said. “The fight for justice is never-ending, you have to keep moving the ball.”

A humble leader

Moses also earned respect for his courage. Those who met Moses, often remarked on the Zen-like calm he seemed to project even in the face of great physical danger. Once, when attacked by a White mob in Mississippi, local sheriffs rushed to his side — joining the mob and beating him in the head with blackjacks. He, like civil rights icon John Lewis, never fought back with violence.

Even when he spoke to the Black sharecroppers he met in Mississippi, Moses was calm and respectful, said Bernard Lafayette, a civil rights activist who worked with Moses and other civil rights campaigns.

“His approach was very different,” Lafayette says. “He wouldn’t go in hollering and screaming to tell people that you should vote. He would sit down and talk to them and find out what were some of the things they wanted to accomplish and then relate that to the vote.”

Derrick Johnson, president of the NAACP, told CNN that Moses’s life should also inspire voting rights leaders to focus on the result of their fight instead of the notoriety that comes with it. Moses, he said, was not a “self-promoter.”

Moses “put community interests before his own ego,” said Johnson, who was a friend of Moses’s. “In this age of social media, you have many people who are more concerned with the number of followers and clicks and likes than they are with the desired outcome that they are fighting for.”

‘The organizer of the organizers’

Moses helped change the trajectory of voting rights with Mississippi Freedom Summer. It drew national attention to the brutal conditions Blacks faced in the South when trying to vote. Three civil rights workers were killed that summer trying to register Black voters. The Voting Rights Act, dubbed the crown jewel of the civil rights movement, was passed the following year in 1965.

One of the legacies of that summer was how it transformed the local Black people in Mississippi whose talents Moses helped nurture. Many went into politics and became community leaders. One of the most famous examples of local leadership was Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper who became a charismatic voting rights organizer.

Moses also showed in Mississippi that voting rights advocates worked better when they put their agendas aside and worked together. The civil rights movement was full of rivalries and competition between groups. But under Moses’s leadership, many groups were able to set aside their dueling agendas, at least for a time, says Ravi Perry, a historian and chairman of the political science department at Howard University.

“During an era when people had so many different ideas about how to create change, he was able to hear these different arguments and build consensus,” Perry says. “He was the organizer of the organizers.”