President Joe Biden may have started this week with a foreign policy-heavy schedule, but his decision to launch intensive in-person engagement at the White House on Wednesday makes clear the reality: The stakes for his domestic agenda simply could not be higher at this moment, nor the impasses more complicated to reconcile.

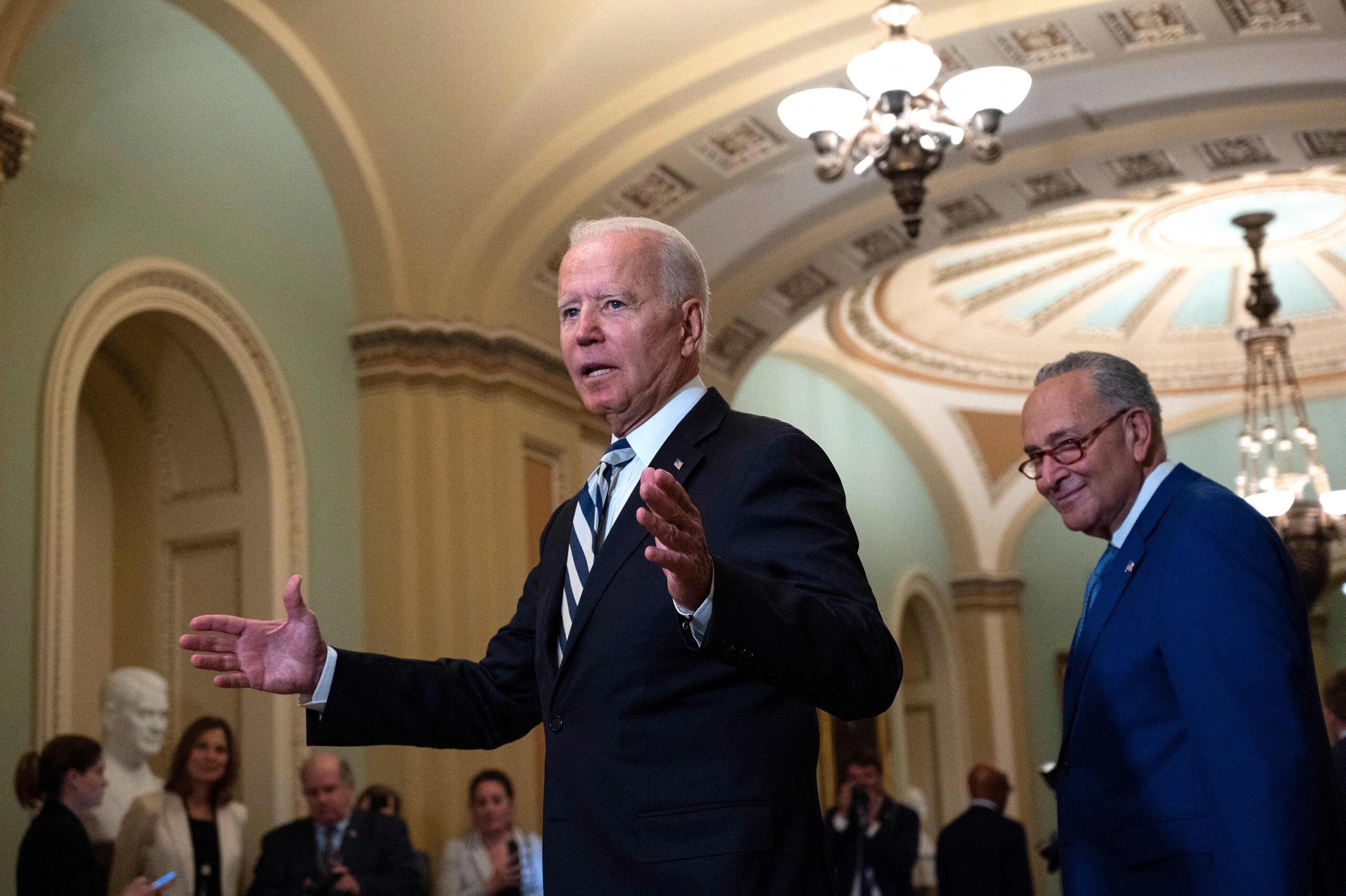

Biden will meet with a series of Democrats throughout the day on Wednesday, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. It will mark the most expansive in-person engagement Biden has undertaken since he took office and underscores just how critical this moment is for his presidency. Officials say he’ll also be on the phone with Democrats regularly in the days ahead as well.

Biden and his team have spent months quietly focused on revitalizing the White House-congressional relations in the wake of his predecessor, from the President’s role on down. Past legislative victories show those efforts have paid off — to this point. But this is now the ultimate test — far more complex and high stakes than any past negotiation.

And there’s nothing short of Biden’s central first year (and perhaps first term) agenda riding on it.

A short-hand to do list:

- Fund the government by September 30

- Raise the debt ceiling by sometime in mid-October

- Vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill in the House by September 27

- Find a way to get enough progress on the social safety net bill so progressives don’t tank the infrastructure bill.

The test

Biden has long made clear to his closest aides a view that he has a better read on Capitol Hill than anyone on his team. There’s good reason for that — he’s a 36-year veteran of the institution and has relationships across both parties that span, in some cases, decades.

Those relationships, and what advisers consider an innate sense of what makes lawmakers tick, have been viewed as a critical component of his legislative efforts throughout the last nine months.

It’s clear, however, that this is a very different moment than any encountered by this White House up to this point. Calls to the White House for Biden to get intimately involved in trying to mollify warring factions inside his party and bridge very real and intractable divides have grown in recent days, multiple sources say.

This, in other words, is the moment someone with Biden’s resume and pedigree should be tailor-made for as president. Whether that’s enough given the scale of the current disagreements is the biggest outstanding question.

On Wednesday, Biden is set to meet with the head of the House Progressive Caucus Rep. Pramila Jayapal, a key member to getting his bipartisan infrastructure bill through next Monday when it comes up for a vote in the House.

Other progressives including Reps. Mark Pocan and Jim McGovern will also be going to the White House on Wednesday, according to a source.

But Biden isn’t just talking to the left. He will also meet with key moderates, a sign of how his White House is trying to bridge the gap between the party’s two factions.

He will meet with Reps. Josh Gottheimer of New Jersey, Stephanie Murphy of Florida and Suzan DelBene of Washington.

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer to reporters on Biden’s meetings, per CNN’s Annie Grayer: “I hope he is the secret sauce.”

Another House Democrat, to CNN last night, on the Biden meetings: “If this doesn’t shake things loose, we’ve got a serious problem.”

Something to consider

As it currently stands, by Tuesday of next week, there’s a very real possibility Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure bill will have failed, his $3.5 trillion economic and climate package remains stalled and there is no clear option to forestall a government shut down or debt default.

That, more the anything else, underscores the moment the White House and congressional Democrats currently find themselves in.

And yet, the White House and Democratic leaders are settling in for a longer slog here. Yes, deadlines are approaching, but everyone is bracing for the reality that a failed (or pulled) vote next week won’t be the end of things.

Sometimes it takes teetering off the edge for rank-and-file members to actually see what it at stake.

There has long been a central ethos inside the West Wing, particularly amongst the legislative team, to keep their heads down and just keep plugging away. Where other high-level officials mock pundits who pronounced the premature death of the bipartisan infrastructure plan, the legislative operation largely ignored the chatter and instead focused on identifying what members needed and then found a way to get there.

That, according to multiple officials, is the approach they are taking now.

Granted, the problems they’re facing appear Everest-level when compared to past mole hills. But in any legislative agreement, no matter how complex, multi-part or high-wire act, there is a sweet spot. The last several weeks, from Biden’s meetings and calls on down, have been driven by slowly working their way toward that point.

To be clear, there are also times when a sweet spot just doesn’t exist and things simply implode. There’s no question the process is closer to that point than any of the past high-stakes efforts.

But it’s not there yet, no matter how tenuous things may appear, so the work continues.

Why a deal gets done

Because it has to get done. That sounds simplistic — and given the scale and transformative nature of what’s being considered, it is. Every line of legislative text matters, and could shift the scale of programs or effects on individuals, companies or climate policy by billions of dollars.

But the overarching point, made by both Democratic leaders and White House officials alike, is that now is the moment to unify for *something.* It may not be perfect, but delivering on what was promised — and make no mistake, while the scale of Biden’s proposal is sweeping, it tracks closely to exactly to all of the key planks of his agenda he laid out before he took office — is paramount from a policy and political perspective.

As one White House official told CNN: “There’s a way to thread the needle here.”

What, exactly, that way is remains unclear to just about everyone.

But the alternative is, quite literally, nothing. No bipartisan infrastructure bill. No sweeping economic and climate package. Nothing.

There remains a sense inside the White House that when push comes to shove, that’s an alternative no Democrat, regardless of where they land ideologically, will conclude is acceptable.

Why everything implodes

The reality, despite the it-must-get-done attitude from both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue, is the policy details are exceedingly important here. Progressives come from the view that they’ve been good soldiers to this point, accepting things they didn’t want or below their asks in both the $1.9 trillion Covid relief law and the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure package.

They see no reason they should once again be the ones who make all the compromises.

As independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has made clear, they view the $3.5 trillion topline as a compromise — and a significant one at that.

And yet nobody involved in these talks thinks $3.5 trillion is even remotely possible at this point.

Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona have said for weeks they won’t get there, and Sinema made that very point clear to Biden in her private one-on-one meeting with him last week.

Step back for a minute: Democrats are rushing to finish this — or get very close — by next week, and they still haven’t settled on how much it should cost. This is a logistical nightmare for aides and members trying to figure out what else will fit in the bill. One Democratic aide laughed when asked if this package was going to be done by Monday, revealing just how tenuous and impossible this timeline is.

And Sinema and Manchin don’t just want a lower topline. They fundamentally have a difference of opinion on what programs are actually needed right now and who in the country needs help the most. They’ve floated means testing some of the central programs inside the proposal, a massive problem for some on the left.

Manchin has made no secret of his distaste for certain climate provisions, which progressives view as borderline redlines. Aides say a carbon tax that had been entertained has already been scrapped because it’s been viewed as a problem for moderates.

The thicket of potential issues in the tax provisions the White House and Democrats plan to utilize to finance the bulk of the proposal are too numerous to list out at this point and don’t land neatly along the lines of the traditional progressive and moderate split we’ve seen so often. Manchin and Sinema are just the tip of the iceberg of all the votes that can be lost.

Hovering over all of this is the element of time. All of these things need to be on the way toward, or very close to, a final agreement before the September 27 House vote on the Senate-passed bipartisan infrastructure bill.

It became clear Tuesday just how close everything is to a doomsday scenario for Biden’s agenda.

Schumer made clear, when asked by a reporter, that the chamber would not pass the economic and climate package by September 27. In fact, he said he didn’t even think it would be procedurally possible to do so.

A few hours later, Jayapal emerged from a 90-minute meeting with Pelosi and told reporters roughly half of her caucus would vote against the infrastructure bill on September 27 unless the economic and climate package “is passed the Senate.”

When told some think progressives are bluffing, Jayapal responded: “Try us.”

Comparing apples to apples to zucchinis

There have been numerous references to past legislative victories as the rationale for why an agreement will eventually be reached here. There is validity to some of those points.

Here’s the biggest reason why comparisons to what happened with the Covid relief law, or the bipartisan infrastructure package or even the $3.5 trillion budget roadmap, fall short: There’s no next bill.

Throughout the aforementioned processes, Democratic leadership and the White House could always point to the looming economic and climate package as the place where any items that didn’t make the cut could eventually land.

That position, fraught as it may have been, was critical. To pull from a saying often used in college basketball’s March Madness, it was pure “survive and advance” strategy — make it to the next stage of things.

But eventually it comes time to deliver on those promises. This is that moment. There is no “next” major package. There’s no new economic or climate bill in the works. This is the ballgame.

Interestingly, Pelosi tried to hedge a bit on this in a letter to House Democrats on Monday — the same letter that openly acknowledged the $3.5 trillion topline was falling by the wayside.

“The President has set us on a course that does not end with this reconciliation bill,” Pelosi wrote.

OK, maybe in theory. But in practice? Nope.

Another critical factor

One thing to keep in mind in this moment is this is no longer a chamber-by-chamber process. It simply can’t be anymore.

Moderate House Democrats have made clear they won’t sign off on anything that will be whittled down in the Senate and Pelosi has privately been telling her members that she won’t force a vote on a bill in the House that is dramatically different than what the Senate will eventually pass. Moderate members are taking her at her word because the most devastating thing for a swing district member to do is vote on controversial legislation for the team that eventually goes nowhere.

It would be cap and trade, or getting “BTU’d,” all over again and members who are facing tough reelections have been reassured — at least up until this point– they won’t have to just walk the plank for no reason.

Which means the White House and lawmakers are now in an intensive period of de facto pre-conferencing — trying to lock up an agreement that will pass both chambers in the same general form.

Notably, while everyone was focused elsewhere in the month of August, White House officials and their Hill counterparts were working feverishly to do just that.

Significant portions of a final package are largely written and could be quickly pulled together once lawmakers decide where they want to end up. Think of it like a buffet of options. It’s out and ready, but members have to decide what they want to put on their plate.

The most critical and contentious areas have been left for leadership and lawmakers to grapple with and that’s what they are doing now.

Something drawing consternation

It’s not clear where everyone is.

One of the challenges so far, members and aides say, is that it isn’t entirely clear yet what some members want. In caucus lunches, Manchin has pointed to his sticking points pretty openly. He talks about them in the hallways, he lays them out neatly in op-eds. But, Sinema has taken a different approach.

She’s not laying every demand out in the open. In fact, she’s very quick to point out she prefers it that way.

She’s talking regularly with Schumer. She has met with Biden and speaks to him by phone.

She was part of an hour-long conversation with him and fellow moderates on Tuesday. She continues to confer with former House colleagues. She met with Gottheimer on Tuesday.

But, Sinema is not advertising what she wants, and it makes it hard to predict where that magical sweet spot between progressives and moderates actually is going to be.