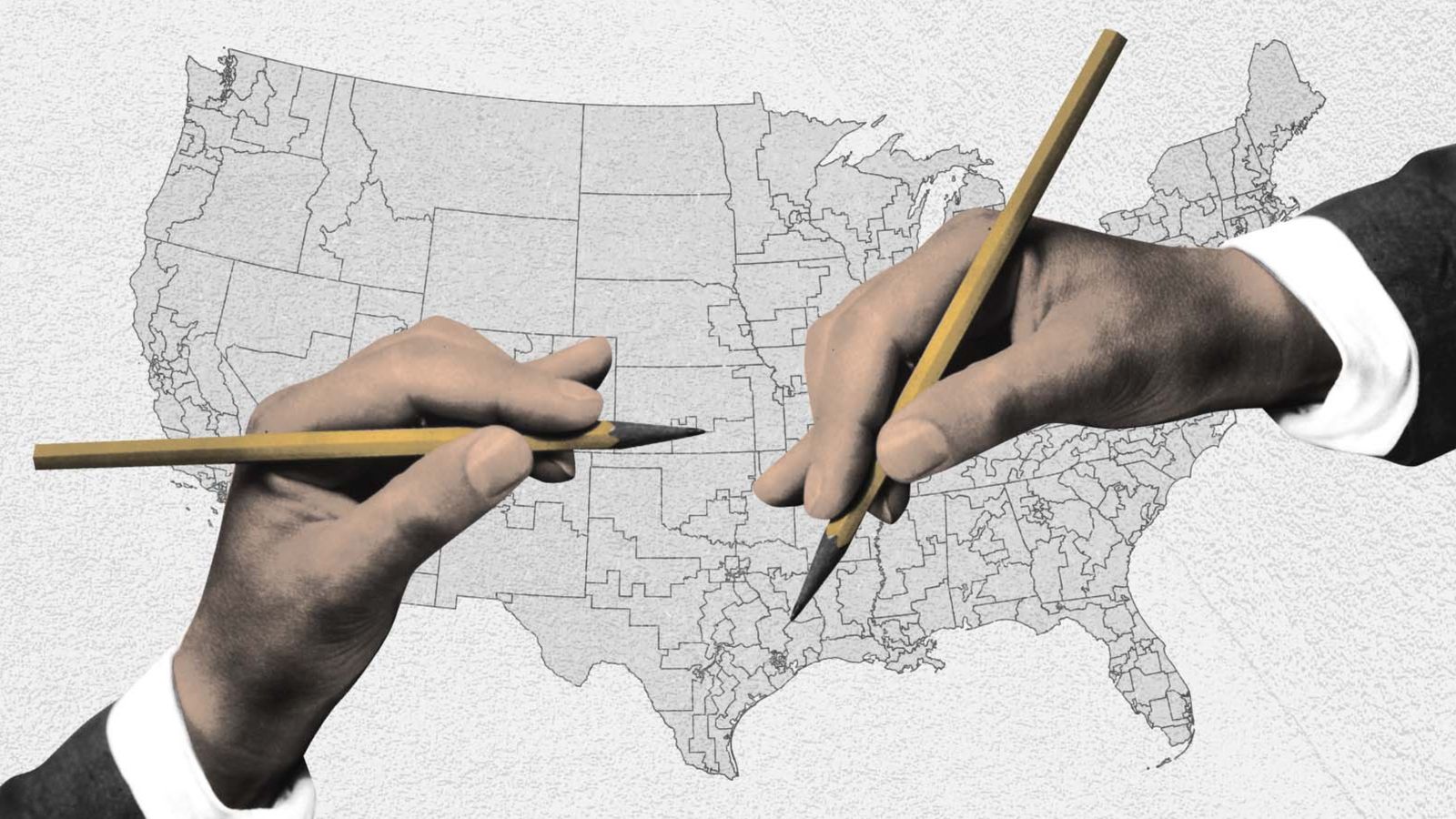

In states like Texas and North Carolina, Republican lawmakers in charge of redrawing the political maps for the next decade say that the new plans are “race blind.” Their opponents in court say that the claim is implausible and one that, in some situations, is at odds with the Voting Rights Act.

Several lawsuits, including from the Justice Department, allege that the maps drawn after the 2020 census discriminate against voters of color.

Between a 2013 Supreme Court decision that scaled back the federal government’s role in monitoring redistricting and a 2019 ruling that said partisan gerrymanders could not be challenged in federal court, voting rights advocates have been left with fewer tools to address what they say are unfair and illegal redistricting plans.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in the states where the redistricting legal fights have been most pitched have adopted an approach that claims that racial data played no role as they drew the maps for the next 10 years. Legislators say they’re avoiding the use of race data after decades of litigation where they’ve been accused of unconstitutionally relying on race to gerrymander.

“I don’t view this as a serious legal defense, but more of a PR defense,” said Thomas Saenz, the president and general counsel of Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which is suing Texas lawmakers over their new maps.

Challengers to the maps say that such an assertion of “race blind” maps is dubious as well as a betrayal of states’ obligations under the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits racial discrimination in redistricting. The law requires that in some circumstances, map-makers must draw plans in a way that creates minority-majority districts where voters can elect the candidates of their choice. In lawsuits alleging a failure to comply with the law, states like Texas have been accused of drawing maps that instead dilute the votes of communities of color.

Legislators may be trying to “immunize” themselves from most of the claims that are used in court to strike down redistricting maps, according to Nate Persily, a Stanford Law School professor and redistricting expert.

“By saying race was not in the minds of the people who drew the lines, you potentially get out of those constitutional causes action that you are intentionally diluting the vote of racial minorities or that race was the predominant factor in the construction of a district,” Persily told CNN, adding that such an approach doesn’t shield map-drawers from cases alleging Voting Rights Act violations.

Lawmakers’ description of maps as “race blind” is both “political rhetoric” and “test case rhetoric,” said Ben Ginsberg, a former Republican redistricting lawyer who is not involved in the current lawsuits. “But still, the standard is you can’t dilute minority voting power and minority opportunity to vote for their candidates of choice. And by not using race data they run the risk of being found to have diluted minority voting strength from what’s in the current map.”

‘They know where Black voters live’

For decades, North Carolina has been on the frontlines on the legal battles over redistricting, and the fight after the 2020 census stands to be the same.

Early next month, a state court will consider the new maps in a trial covering claims of partisan gerrymandering (which can still move forward in some state courts) and racial vote dilution in the new plans.

Among the allegations in the case is that that the legislature — by excluding the use of race data when drawing the maps this year — violated North Carolina Constitution, as interpreted by state Supreme Court decisions. The legislators leading the redistricting process said in public hearings that they believed their approach is in line with law.

The new map reduced the African American voting age population a congressional district held by Democratic Rep. G.K Butterfield, the former chair of the Congressional Black Caucus who is now retiring, citing the way his district was redrawn. How the percentage of Black voters was shrunk in several state Senate and House districts is being challenged in the state court case as well.

In public hearings, the Republican legislators defended their redistricting process and said that they didn’t read the law as requiring them to incorporate race into their approach.

North Carolina Sen. Ralph Hise, a Republican and co-chair of the legislature’s redistricting commission, said in a statement to CNN, that the state was sued for using race in the 2011 redistricting process.

“So during this process, legislators did not use any racial data when drawing districts, and we’re now being sued for not considering race,” he said. “The only constant here is Democratic litigants selecting arguments, no matter how contradictory, to try to convince a court to order maps that favor Democratic candidates.”

Allison Riggs — an attorney for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which is involved in the state court case — described that attitude as “petulant,” telling CNN that Republican lawmakers lost racial gerrymandering cases in the last cycle because they were using racial data to pack voters of color into fewer districts, rather than to help those voters.

“No one seriously believes that legislators can or are doing this race blind,” Riggs said. “A representative who represents Pitt County here in North Carolina is a representative, is an elected official, because he, she or they knows where voters live. They know where Black voters live in the county.”

Pat Ryan, spokesperson for North Carolina Senate Republicans, said that how the plaintiffs “have resorted to claims of mind-reading shows just how ridiculous these lawsuits are.”

What the law requires

In tension with legislators’ obligations under the Voting Rights Act are the limits the Constitution — under Supreme Court precedent — put on the use of race in redistricting.

The Supreme Court has said, via the 1993 decision in Shaw v. Reno, that use of race as a sole factor in drawing districts unconstitutional in most circumstances. However, the Voting Rights Act presents the sort of compelling government interest that allows for race to be considered.

Jason Torchinsky — a Republican election lawyer who has defended North Carolina legislators in redistricting cases in the past, but is not involved in the current cases in North Carolina or Texas– told CNN that map-drawers have to walk the line between their VRA obligations and not running afoul of the Constitution.

“Legislatures have to use very localized data to determine if they are required to draw [Voting Rights Act] Section 2 districts,” Torchinsky said. “If they are, then they have to consider race in those parts of the states because they’re required to under the Voting Rights Act.” But when states aren’t required to draw VRA districts, Torchinsky said, the use of race could pose a potential Constitutional problem.

Ryan, the spokesperson for the North Carolina Senate GOP, pointed to a 2016 federal court decision in which the legislature was faulted for drawing maps with race data lawmakers said they were using for VRA compliance, when, according to the court, the circumstances didn’t require the use of race to comply with the VRA.

“We have been presented with no evidence that anything has changed since that decision from just a few years ago,” Ryan said in an email. “And so, having been told recently by a court that we did not have evidence of the conditions that would justify the use of racial data in redistricting, we chose not to use racial data this time around.”

Texas state Sen. Joan Huffman, a Republican who led the state’s redistricting process, also claimed in public hearings that the state’s maps were drawn in a race blind way. Her office did not respond to CNN’s inquiry, but she told the Texas Tribune that legal advisers had vetted the maps — which now face several challenges under the Voting Rights Act — for VRA compliance. She declined to say, according to the Tribune, how those advisers made those assessments.

In court filings, Texas has signaled plans to argue that the relevant Voting Rights Act provision should not apply to redistricting.

The Justice Department, in its lawsuit alleging the maps violate the VRA, argues that that there is evidence that race drove the drawing of Texas’ new maps and that it was used to dilute Latino voting power. Among the districts the DOJ is challenging is a congressional district at Texas’ Southwest border that was assembled by breaking up individual precincts. “While accurate racial data is available below the precinct level, accurate political data is not, suggesting that many precinct splits have a racial basis,” the DOJ said, while pointing out that the reworking of the district led to a removal of half of its Latino citizen voting age population.

Saenz, of MALDEF, told CNN that the evidence suggested that “race was the predominant factor.”

“You’re making fine tunes, where really the only thing you can look at is race, there is no other way to explain why you cut a district that way,” Saenz said.