First celebrated in 1979, Black August was created to commemorate famed Panther George Jackson’s fight for Black liberation.

For Jonathan Peter Jackson, a direct relative of two prominent members of the Black Panther Party, revolutionary thought and family history have always been intertwined, particularly in August.

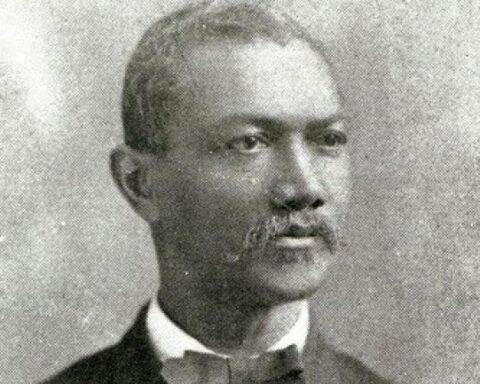

That’s the month in 1971 when his uncle, the famed Panther George Jackson, was killed during an uprising at San Quentin State Prison in California. A revolutionary whose words resonated inside and out of the prison walls, he was a published author, activist and radical thought leader.

To many, February is the month dedicated to celebrating Black Americans’ contributions to a country where they were once enslaved. But Black History Month has an alternative: It’s called Black August.

First celebrated in 1979, Black August was created to commemorate Jackson’s fight for Black liberation. Fifty-one years since his death, Black August is now a monthlong awareness campaign and celebration dedicated to Black freedom fighters, revolutionaries, radicals and political prisoners, both living and deceased.

The annual commemorations have been embraced by activists in the global Black Lives Matter movement, many of whom draw inspiration from freedom fighters like Jackson and his contemporaries.

“It’s important to do this now because a lot of people who were on the radical scene during that time period, relatives and non-relatives, who are like blood relatives, are entering their golden years,” said Jonathan Jackson, 51, of Fair Hill, Maryland.

George Jackson was 18 when he was arrested for robbing a gas station in Los Angeles in 1960. He was convicted and given an indeterminate sentence of one year to life and spent the next decade at California’s Soledad and San Quentin prisons, much of it in solitary confinement.

While incarcerated, Jackson began studying the words of revolutionary theoreticians such as Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, who advocated class awareness, challenging institutions and overturning capitalism through revolution. Founding leaders of the Panthers, including Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, were also inspired by Marx, Lenin and Chinese Communist leader Mao Tse-tung.

Jackson became a leader in the prisoner rights movement. His letters from prison to loved ones and supporters were compiled in the bestselling books “Soledad Brother” and “Blood in My Eye.”

Inspired by his words and frustrated with his situation, George’s younger brother, Jonathan, initiated a takeover at the Marin County Superior Court in California in 1970. He freed three inmates and held several courthouse staff hostage, in an attempt to demand the release of his brother and two other inmates, known as the Soledad Brothers, who were accused of killing a correctional officer. Jonathan was killed as he tried to escape, although it’s disputed whether he was killed in a courtroom shootout or fatally shot while driving away with hostages.

George was killed on Aug. 21, 1971, during a prison uprising. Inmates at San Quentin prison began formally commemorating his death in 1979, and from there, Black August was born.

“I certainly wish that more people knew about George’s writings (and) knew about my father’s sacrifice on that fateful day in August,” said Jonathan Jackson, who wrote the foreword to “Soledad Brother” in the early ’90s, shortly after graduating from college.

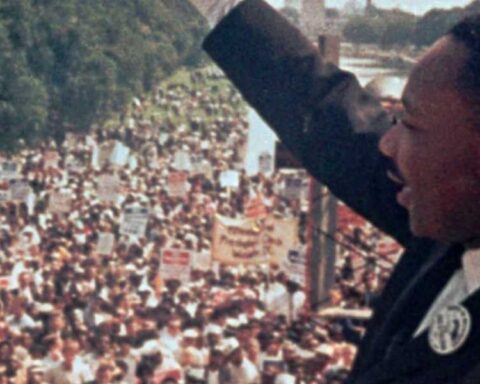

Monifa Bandele, a leader in the Movement for Black Lives, a national coalition of BLM groups, says Black August is about learning the vast history of Black revolutionary leaders. That includes figures such as Nat Turner, who is famous for leading a slave rebellion on a southern Virginia plantation in August 1831, and Marcus Garvey, the leader of the Pan-Africanism movement and born in August 1887. It includes events such as the Haitian Revolution in 1791 and the March on Washington in 1963, both taking place in the month of August.

“This idea that there was this one narrow way that Black people resisted oppression is really a myth that is dispelled by Black August,” said Bandele, who is also a member of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, a group that raises awareness of political prisoners.

“And what we saw happen after the 1970s is that it grew outside of the (prison) walls because, as people who were incarcerated came home to their families and communities, they began to do community celebrations of Black August,” she added.

The ways of honoring this month also come in various forms and have evolved over the years. Some take part in fasting, while others use this time to study the ways of their predecessors. Weekly event series are also common during Black August, from reading groups to open mic nights.

Sankofa, a Black-owned cultural center and coffee shop in Washington that has served the D.C. community for nearly 25 years, wraps up a weekly open mic night in honor of Black August on Friday. The event has drawn local residents of all ages, many who have shared stories, read poetry and performed songs with the theme of rebellion.

“This month is all about resistance and celebrating our political prisoners and using all of the faculties that we have to free people who are in prison, let me say, unjustly,” emcee Ayinde Sekou said to the crowd during a recent event at Sankofa.

Jonathan Jackson, George’s nephew, also believes that there are largely systemic reasons as to why Black August, and his family history specifically, are not widely taught.

“It’s difficult sometimes for radicals who were not assassinated, per se, to enter into the popular discourse,” he said. “George and Jonathan were never victims. They took action, and they were killed taking that action, and sometimes that’s very difficult to understand for people who will accept a political assassination.”

Jackson hopes to honor his father’s and uncle’s legacy through documenting the knowledge of elders from that era, as a means of continuing the fight.

“We need to get those testimonies. … We need to understand what happened, so that we can improve on what they did. I think now is as good a time as any to get that done,” he said.