Several surviving members of the Little Rock Nine, a group of students who in 1957 integrated Little Rock Central High School under threats of violence from white segregationists, are denouncing the Arkansas Department of Education’s restrictions on an Advanced Placement African American Studies course.

The state is not barring students from taking the class but has cautioned that the coursework may not count toward the state’s high school graduation requirements. The Arkansas Department of Education has argued that since the course is still being piloted, it’s unclear whether it runs afoul of a state law signed by Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders in March banning the teaching of “critical race theory.”

“I think the attempts to erase history is working for the Republican Party,” said Elizabeth Eckford, who joined eight other Black teenagers in desegregating Little Rock Central High School nearly 66 years ago. “They have some boogeymen that are really popular with their supporters.”

The Arkansas Department of Education defended its decision, saying in a statement that, “Until it’s determined whether it violates state law and teaches or trains teachers in CRT and indoctrination, the state will not move forward. The department encourages the teaching of all American history and supports rigorous courses not based on opinions or indoctrination.” The state already offers an African American history course, the department noted.

A spokesperson for Sanders did not immediately respond to a request for comment. When asked about the course on Fox News Thursday, Sanders responded by saying that she wants to focus on improving students’ performance rather than pushing a “propaganda leftist agenda.”

Central High offered the pilot version of the course last school year. It will continue to do so this school year, a representative said, as will several other Arkansas high schools.

The interdisciplinary course stretches from the African diaspora to the present and includes topics like slavery, the Black Power Movement and Reconstruction. The course framework mentions a protest song, “Fables of Faubus,” about the unrest that exploded around the Little Rock Nine push, as an example in a unit about the Civil Rights Movement.

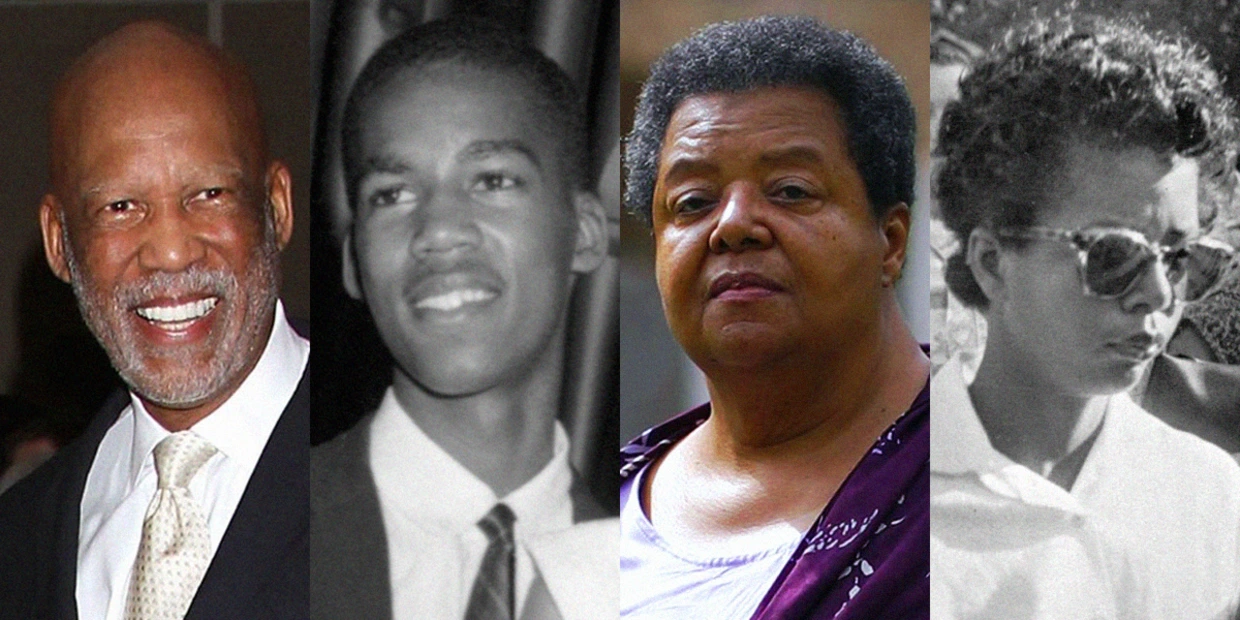

A photograph of a 15-year-old Eckford wearing sunglasses as a white teenage girl harasses her is one of the most recognizable images of the abuse inflicted on Black children during the racist resistance to school desegregation. In the fall of 1957, Arkansas’ defiance of a court order that prevented Eckford and her peers from entering the high school culminated in President Dwight D. Eisenhower intervening by having federal troops escort the group.

Terrence Roberts, 81, another member of the Little Rock Nine, reflected on how the federal government’s show of force wasn’t always enough to protect Black children crossing the color barrier.

“All nine of us suffered physically and emotionally,” he said of the first Black students attending Central High. One of the worst moments for Roberts was when a white student wielding a baseball bat called him the N-word, and said, “If you weren’t so small,” before dropping the weapon and backing off.

“I’m thinking, ‘Wow, salvation by stature,’” he said.

Roberts knows that there are those who don’t want to confront that history. At some commemorations of the Little Rock Nine, he said, there have been people who don’t want old photographs of angry crowds shown. Roberts suspects that those who once harangued them as children don’t want the evidence displayed.

But the truth of those turbulent times is one he’s adamant that students need to know.

At a “bare minimum,” he said, there shouldn’t be “laws restricting their ability to learn, or what they could learn.”

Roberts said he wasn’t surprised at the state’s pushback to the AP African American Studies course. He’s watched the spread of laws across the country limiting the ways race is brought up in the classroom and called bans on critical race theory “ridiculous.”

He welcomed the news that Central High School was continuing with the course, but acknowledged more battles lie ahead.

“I know there are voices pushing back,” he said. “The question is, will they be successful?”

Ivory Toldson, the director of Education Innovation and Research at the NAACP, said officials censoring what can be taught are channeling their energy into the wrong battles.

Civil rights advocates and education policy experts have long highlighted racial disparities in AP course participation and access. Black children, Toldson said, often don’t have the opportunity to sign up for the rigorous offerings, which can earn students college credits while they’re still in high school.

“These are the larger issues I wish they would talk about as they go on defense about this issue,” he said. “They really should be setting forth the plan to make sure all Black students in Arkansas have equal access to a quality education.”

Toldson, who spoke this week with five members of the Little Rock Nine, said that they see the criticism of the AP course “as a broader attack on Black history.”

Melba Beals, who participated in the call, also shared a reflection with the NAACP vowing that future generations would take up “the banner” for civil rights that the Little Rock Nine helped carry.

“Keep kicking,” she wrote. “See how many more heroines and heroes you can build.”