By Nicole Chavez

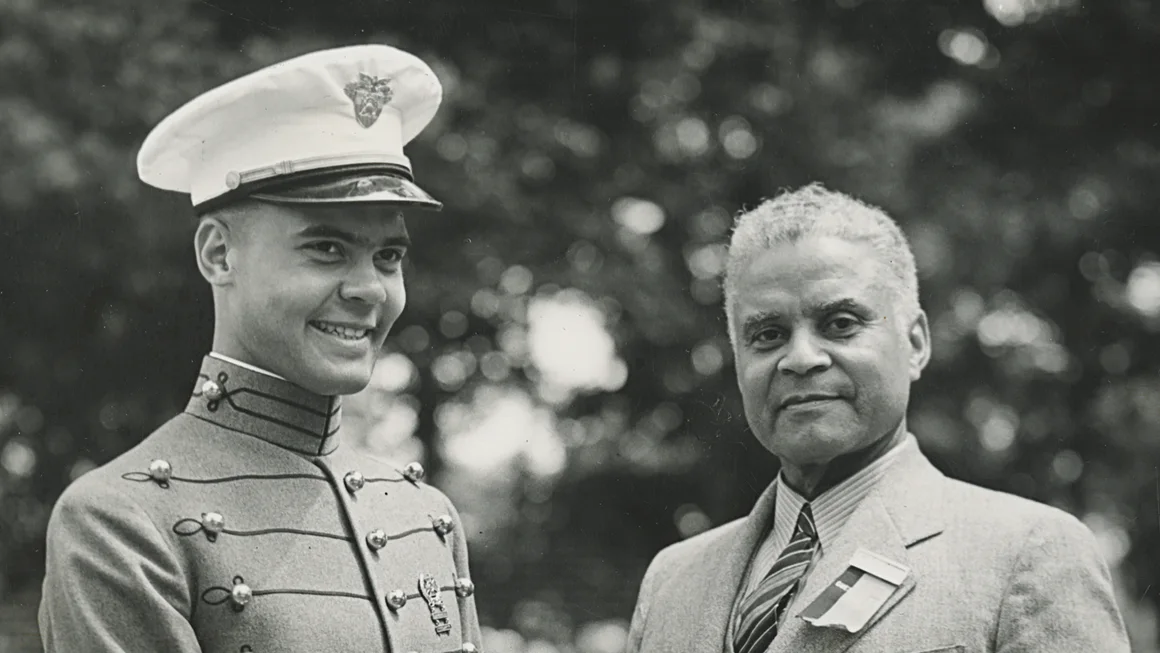

Despite knowing they would likely be relegated to support roles due to the color of their skin, a father and son chose to make the military their lifelong career. Determined to succeed, they became America’s first Black generals.

In 1940, Benjamin O. Davis Sr. became the first Black person to achieve the rank of brigadier general in the US Army.

His son, Benjamin O. Davis Jr., followed in his footsteps by joining the military and later commanding the famed Tuskegee Airmen. Twenty years after his father made history, Davis Jr. became the first Black brigadier general in the Air Force in 1960.

“Davis Sr. and Jr. were both extremely influential figures in the effort to increase opportunities for African Americans in the military,” said J. Todd Moye, a history professor at the University of North Texas who directed the National Park Service’s Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project in the early 2000s.

Black people have held roles in the US military since the Revolutionary War, even as they have endured racism and discrimination for centuries. During the Civil War, Black soldiers served in segregated units and were later shut out of leadership opportunities during World War I and in World War II, when less than 10% of veterans were non-White.

Davis Sr. was born in Washington, DC, less than 20 years after the ratification of the 13th amendment, which abolished slavery.

After participating in his high school’s cadet program, Davis Sr. joined the military during the Spanish-American war, serving in the DC’s National Guard with the 8th US Volunteer Infantry regiment before enlisting in the Army in 1899, according to the Army’s Center of Military History.

He was assigned to the all-Black 9th Cavalry, one of the four regiments that became known as the Buffalo Soldiers, and he served in the Philippines and at the US-Mexico border. Like many Black service members, Davis Sr. did not serve on the front lines during World War I and instead worked as a supply officer.

A 1925 study by the Army War College falsely concluded that Black people lacked the intelligence, ambition and courage to serve in prominent positions within the US military and should not be placed over White officers or soldiers. This policy and the ideology behind it prevented many Black soldiers from advancing through the military’s ranks, including Davis Sr., who was continuously assigned to serve as professor of military science and tactics despite his strong preference for duty with troops.

“He got bounced around from post to post, and to ROTC leadership roles on campuses around the country, mainly because the Army felt like an African American just could not lead White soldiers,” Moye said. “They thought that White soldiers and lower-level White officers just could not be expected to take orders from a Black man. So, there were very few opportunities for him.”

He was collectively shunned for 4 years at West Point

Davis Jr. grew up watching his father’s courage to fight for his ambitions in the face of discrimination. It became something that he himself would mirror time and time again through his adult life.

Davis Jr. put his dream of becoming a pilot aside and chose to become a military officer by attending West Point. Securing a nomination was complicated. Rep. Oscar S. De Priest of Illinois, the first African American elected to Congress in the 20th century, was willing to nominate him but could only select a candidate from among his constituents. So, Davis Jr. moved alone to Chicago for nearly two years to secure the nomination and his spot at West Point.

In 1932, he received orders to report to West Point and four years of shunning began. He roomed alone, ate by himself in the cadet mess hall and no one spoke to him except on official business. This treatment was usually a punishment that cadets carried out against those who violated the honor code but in his 1990 autobiography, Davis Jr. wrote that he was “silenced solely because cadets did not want Blacks at West Point.”

“Their only purpose was to freeze me out. What they did not realize was that I was stubborn enough to put up with their treatment to reach the goal I had come to attain,” he added.

When he graduated in the top 12% of his class in 1936, Davis Jr. was the fourth Black cadet to graduate from West Point and the first one to do so in nearly 47 years.

But with no opportunities for Black officers to fly, Davis Jr. joined an infantry regiment. Like his father, he later became a professor of military science and tactics at what was then called the Tuskegee Institute.

Doug Melville, Davis Jr.’s great-nephew who recounts the Davises journey and legacy in his book “Invisible Generals: Rediscovering Family Legacy, and a Quest to Honor America’s First Black Generals,” said the father and son spent four years traveling together to Black colleges and training young men looking to join the Army.

“They were telling them: ‘One day your time will come, keep your chin up, look straight ahead and be ready,’” he said. “Ultimately those are the men that Ben Jr. recruited to become the Tuskegee Airmen.”

WWII drove social change and a breakthrough for Black soldiers

The opportunity they had been preparing for came in the early 1940s as it became clear that the US would be entering World War II and Black workers threatened to march on Washington, protesting job discrimination and segregation in the military.

On October 25, 1940, Davis Sr. was temporarily promoted to brigadier general by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Months later, Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Committee on Fair Employment Practice to prevent discrimination in defense and government jobs.

Moye said the overall changes in the military, including Davis Sr.’s promotion, were significant because until that point, the Army’s position had been to deny Black Americans opportunities to advance, much like the rest of society at the time.

“American schools are segregated, American churches are segregated, all of these other institutions in America are segregated (and) the Army shouldn’t be expected to be out in front of all of those other institutions,” Moye said, referring to how the armed forces viewed their role in the nation’s desegregation movement.

“So, (the Army) provided no opportunities for African Americans to lead troops, it provided no opportunities before 1940 for African Americans to fly airplanes, there were no African Americans in the Marine Corps,” Moye added.

In 1942, Davis Jr. graduated in the first class of pilots in a newly-created unit of Black military aviators at Alabama’s Tuskegee Army Airfield – a unit now known as the Tuskegee Airmen. That August, he assumed command of the 99th Fighter Squadron, the first unit of Tuskegee Airmen, which engaged in combat in North Africa and Sicily.

Although the Tuskegee Airmen were aware they were breaking racial barriers and making history, Moye, who has met and interviewed many airmen over the years, said their motivations varied.

“A lot of them say ‘I just wanted to be a pilot and, you know, the other stuff was sort of extracurricular to me,’ but a lot of them wanted to do it because they wanted to break barriers,” Moye said. “They wanted to prove that African Americans could do everything that White Americans could do.”

Following the success of the Tuskegee Airmen during WWII, Davis Jr. joined the US Air Force upon its split from the Army.

In 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued an executive order creating the President’s Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services, leading Davis Jr. to become directly involved with integration efforts in the US Air Force, Melville said.

While his father retired from the military before the start of the Korean War, Davis Jr. served during both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. In 1960, he became the first Black brigadier general in the US Air Force.

He retired a decade later.

The fight for equality went on

While the generals broke barriers and successfully fought for the advancement of Black Americans, change and increased opportunities have been slow to take hold in the military and beyond, scholars and historians told CNN.

Black men are currently overrepresented in the US military when compared to the civilian labor force, but they remain underrepresented in officer ranks.

Le’Trice Donaldson, an assistant professor of history at Texas A&M University Corpus Christi whose research has focused on African Americans in the military, said the lack of combat experience remains a challenge for the advancement of Black service members.

“In order to move up and become a general you need a certain level of combat experience and African Americans are almost always shuffled into transport or support staff divisions, and that is going to limit your ability to be promoted,” Donaldson said.

After retiring from the military, Davis Jr., like other Tuskegee Airmen, sought to continue flying as a commercial pilot but the career he expected to have never materialized. Melville said he applied for jobs at multiple airlines but never received an offer, despite his accomplishments.

Still, he found a way to stay involved in aviation. In the 1970s, Davis Jr. was named director of civil aviation security for the Department of Transportation, where he led the implementation of measures to counter aerial hijackings and oversaw the training of agents of what now is known as the Federal Air Marshal Service.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton promoted Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., to the rank of four star general, describing him during the ceremony as “a hero in war, a leader in peace, a pioneer for freedom, opportunity and basic human dignity.”

“Our armed forces today are a model for America and for the world of how people of different backgrounds working together for the common good can perform at a far more outstanding level than they ever could have divided,” Clinton said. “Perhaps no one is more responsible for that achievement than the person we honor today.”

Throughout their lives, the Davises were devoted to their families and never sought the spotlight. Melville recalled Davis Jr.’s kindness and how he never wanted to share his past or photos with him and that he didn’t have military regalia in his house.

Years after Davis Jr.’s passing, Melville began researching his family’s history – details that had never been shared with him. He wrote in his book that, at his core, Davis Jr. had a deep desire to overcome discrimination and be known as a general in “an equal way to all others, without qualifiers.”

“Our family went beyond what they needed to do in order to invest in a country that really wasn’t investing in them but they still believed it was the best country in the world, and still believed that positivity and sunlight will shine for our people and that we will earn our place as Americans,” Melville said.